|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Angelo Viggiani dal Montone"

| Line 1,376: | Line 1,376: | ||

<p>ROD: I can; rather there are an infinity of guards, ''conte'', as there can be an infinity of settlements and positions; and it is true that each increment of space that you move the sword from high to low, or from low to high, from the forward to the rear, and the contrary, and from the right side to the left, and the contrary, and each little bit that you retire your foot from place to place, and in sum every infinitesimal movement forms diverse guards, which movements are without number or end. These Masters have, rather, placed names to those more necessary in order to have a way to be able to teach to their disciples with more facility, and having taken such names from some similarity or effect, from which whomever has well considered the semblances of the animals perhaps may have been able more appropriately to say “guard of the Unicorn”, “guard of the Lion”, and other such; but I, who am not a Master of a school, to you, who are not now my disciple, do not intend to give you to understand today all our exercises entirely for practice, but I will select only a ''schermo'' (as I said) with which, coming to blows with your enemy, or assaulted by him, or assaulting him, you can perfectly and preparedly strike him mortal wounds, and make a most secure defense from his; </p> | <p>ROD: I can; rather there are an infinity of guards, ''conte'', as there can be an infinity of settlements and positions; and it is true that each increment of space that you move the sword from high to low, or from low to high, from the forward to the rear, and the contrary, and from the right side to the left, and the contrary, and each little bit that you retire your foot from place to place, and in sum every infinitesimal movement forms diverse guards, which movements are without number or end. These Masters have, rather, placed names to those more necessary in order to have a way to be able to teach to their disciples with more facility, and having taken such names from some similarity or effect, from which whomever has well considered the semblances of the animals perhaps may have been able more appropriately to say “guard of the Unicorn”, “guard of the Lion”, and other such; but I, who am not a Master of a school, to you, who are not now my disciple, do not intend to give you to understand today all our exercises entirely for practice, but I will select only a ''schermo'' (as I said) with which, coming to blows with your enemy, or assaulted by him, or assaulting him, you can perfectly and preparedly strike him mortal wounds, and make a most secure defense from his; </p> | ||

| + | | <p><br/><br/></p> | ||

| − | <p><small>''The names of the seven guards are taken both from their form and from their purpose.''</small></p> | + | {{section|Page:Cod.10723 90v.jpg|3|lbl=90v.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Cod.10723 91r.jpg|1|lbl=91r.1|p=1}} |

| + | | {{section|Page:Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani) 1575.pdf/144|f2|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{section|Page:Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani) 1575.pdf/144|6|lbl=60r.6|p=1}} {{section|Page:Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani) 1575.pdf/145|1|lbl=60r.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p><small>''The names of the seven guards are taken both from their form and from their purpose.''</small></p> | ||

<p>hence I set only seven guards, and these in order to name them conveniently are placed according to the form and the purpose of the guard; I designate offensive or ''difensive'', according to the purpose; ''larghe, strette'', or ''alte'', according to the form; ''perfette'' or ''imperfette'' according to their perfection or imperfection. And if I wanted to show you today the entire art and the entirety of the mastery of arms, stating what are ''tempo'', and ''mezo tempo'', and ''contratempo''; what are guards and how many there are, and how to form them all; how many ways of striking there are, and all the blows, which ones offending and which defending; with how many kinds of arms one can combat, and the protections and advantages that are in each one of them, when one is on foot and on horseback; how many prese there are, and how to form them; and in sum all the military exercises, not only would I not know how to do so easily, but moreover I could not do it in the space of a year. </p> | <p>hence I set only seven guards, and these in order to name them conveniently are placed according to the form and the purpose of the guard; I designate offensive or ''difensive'', according to the purpose; ''larghe, strette'', or ''alte'', according to the form; ''perfette'' or ''imperfette'' according to their perfection or imperfection. And if I wanted to show you today the entire art and the entirety of the mastery of arms, stating what are ''tempo'', and ''mezo tempo'', and ''contratempo''; what are guards and how many there are, and how to form them all; how many ways of striking there are, and all the blows, which ones offending and which defending; with how many kinds of arms one can combat, and the protections and advantages that are in each one of them, when one is on foot and on horseback; how many prese there are, and how to form them; and in sum all the military exercises, not only would I not know how to do so easily, but moreover I could not do it in the space of a year. </p> | ||

| <p><br/></p> | | <p><br/></p> | ||

| − | + | {{section|Page:Cod.10723 91r.jpg|2|lbl=91r.2}} | |

| − | | {{section|Page:Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani) 1575.pdf/ | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani) 1575.pdf/145|f1|lbl=-|p=1}}<br/><br/> | ||

| − | + | {{section|Page:Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani) 1575.pdf/145|2|lbl=60r.2}} | |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 1,391: | Line 1,400: | ||

| <p>CON: At least tell me now what advantage is, and what ''tempo'' is. </p> | | <p>CON: At least tell me now what advantage is, and what ''tempo'' is. </p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani) 1575.pdf/145|3|lbl=60r.3}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>ROD: You have to know, ''conte'', the advantage now can be considered to be in settling yourself in guard, in the striking, and in the stepping. Accordingly it may be said that you settle yourself in guard with advantage when the point of your enemy’s sword is outside your body and not aimed at you, and when the point of your sword is aimed at the body of your enemy in order to offend him, so that you may, in such fashion, easily offend him, and it will be difficult for him to defend himself from you; consequently you will be able to strike him in little time, and in order to defend himself, he will require more time; and conversely, he will find it difficult to offend you, and you will be able to easily defend yourself from him for the selfsame reason, he having need of much, and you of little time. </p> | + | | <p><br/></p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>ROD: You have to know, ''conte'', the advantage now can be considered to be in settling yourself in guard, in the striking, and in the stepping. Accordingly it may be said that you settle yourself in guard with advantage when the point of your enemy’s sword is outside your body and not aimed at you, and when the point of your sword is aimed at the body of your enemy in order to offend him, so that you may, in such fashion, easily offend him, and it will be difficult for him to defend himself from you; consequently you will be able to strike him in little time, and in order to defend himself, he will require more time; and conversely, he will find it difficult to offend you, and you will be able to easily defend yourself from him for the selfsame reason, he having need of much, and you of little time. </p> | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani) 1575.pdf/145|f2|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{section|Page:Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani) 1575.pdf/145|4|lbl=60r.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani) 1575.pdf/146|1|lbl=60v.1|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

Revision as of 06:15, 24 November 2023

| Angelo Viggiani dal Montone | |

|---|---|

| |

| Died | 1552 Bologna (?) |

| Relative(s) | Battista Viggiani (brother) |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) | Lo Schermo (1575) |

| Manuscript(s) | Cod. 10723 (1567) |

| Translations | Traduction française |

Angelo Viggiani dal Montone (Viziani, Angelus Viggianus; d. 1552) was a 16th century Italian fencing master. Little is known about this master's life, but he was Bolognese by birth and might also have been connected to the court of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.[1]

In 1551, Viggiani completed a treatise on warfare, including fencing with the side sword, but died shortly thereafter. His brother Battista preserved the treatise and recorded in his introduction that Viggiani had asked him not to release it for at least fifteen years.[1] Accordingly, a presentation manuscript of the treatise was completed in 1567 as a gift for Maximilian II (1527-1576), Holy Roman Emperor. It was ultimately published in 1575 under the title Lo Schermo d'Angelo Viggiani.

Treatise

Note: This article includes a very early (2002) draft of Jherek Swanger's translation. An extensively-revised version of the translation was released in print in 2017 as The Fencing Method of Angelo Viggiani: Lo Schermo, Part III. It can be purchased at the following link in softcover.

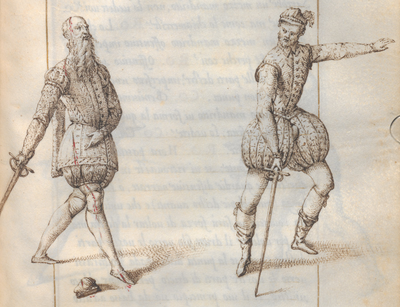

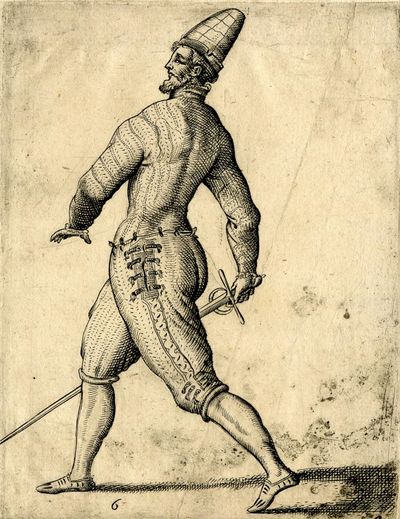

Illustrations |

Presentation manuscript (1567) |

Lo Schermo (1575) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Illustrations |

Presentation manuscript (1567) |

Lo Schermo (1575) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Illustrations |

Draft Translation (from the 1575) |

Presentation manuscript (1567) |

Lo Schermo (1575) |

|---|---|---|---|

Third Part Persons introduced in this discussion:

|

[78r.1] TERZA PARTE Persone introdotte nel ragionamento l'Illustrissimo Signor CONTE d'Agomonte, l'Illustrissimo Signor ALUIGI Gonzaga detto RODOMONTE et l' eccellente Messer LODOVICO Boccadiferro :~ |

[51v.1] TERZA PARTE. Persone introdotte nel Ragionamento. L'ILLUSTRISSIMO SIGNOR ALUIGI GONZAGA DETTO RODOMONTE, L'ILLUSTRISSIMO SIGNOR CONTE D'AGOMONTE, ET L'ECCELLENTISSIMO MESSER LODOVICO BOCCADIFERRO FILOSOFO. | |

ROD: Since we want to exercise ourselves for half an hour, Signor Conte, |

[78r.2] CONTE. VOGLIAMO noi andare di sotto nella stanza, ad essercitarci per un hora, Signor Aluigi? |

[51v.2] RODOMONTE. POI che noi vogliamo essercitarci per meza hora (Signor Conte) | |

[78r.3] ROD. Di gratia Conte, questo istesso desideravo io da voi, fra tanto il Dottore si riposerà. |

|||

[78r.4] CON Nel vero, Signor mio che hò presa gran consolatione hoggi, di quella sì honorata disputa, che insieme havete havuto. |

|||

|

[78r.5] ROD. Vi prometto, Conte, ch'egli hà fatto hoggi, contro di me gran resistenza con i suoi for= [78v.1] tissimi argomenti, e'bellissime risposte, et anchio mi pigliavo gran contento vederlo alle volte montar in colera, et in furore. |

|||

[78v.2] CON. Hò udito dire, che quanto più gli huomini dotti sono assaliti dal furore: tanto dicono cose piu belle. |

|||

Fury is of use to the lettered, and to soldiers, although it arises from choler. first I would desire that we were seized by that fury, which took Homer, Virgil, l’Ariosto, and every other most excellent poet: they said supernatural things; and by which are moved all those lettered men, discussing or writing, that say things rare and excellent; and by which we others accordingly are accustomed to make blows worthy of Mars, whose fury is born of choler. |

[78v.3] ROD. E gli è quel furor poetico, dal quale furon rapiti Homero, Virgilio, l'Ariosto, et ciascun altro Eccellentissimo Poeta; Et nui (ditemi Conte) quando siamo in furore, non ci soviene nella mente sempre qualche disusato capriccio? |

[51v.3] in primi desidererei, che sossimo assaliti da quel furore, dal quale rapiti Homero, Virgilio, l'Ariosto, & ciascun'altro Eccellentissimo Poeta; hanno detto cose sopranaturali: & dal quale mossi tutti i letterati, disputando, ò leggendo dicono cose rare, & Eccellenti; & noi altri perciò siam soliti fare colpi degni di Marte, il qual furore nasce dalla colera. | |

Objection that choler hinders the soldier from perturbing the enemy. CON: How is not better to find oneself without choler? Because as the spirit that is quiet speaks better, and succeeds better in letters, thus also is it in the handling of arms: the spirit being more reposed, the knight is able to better put in execution thoughtful and learned blows, while choler instead impairs reason, taking the same from man, causing him to function without knowing the why and the how. |

[51v.4] CON. Come, non è meglio il ritrovarsi senza colera? perche [52r.1] si come l'anima ch'è quieta, meglio discorre, & riesce nelle lettere meglio; cosi anco nell'armeggiare, sendo l'anima piu riposata, puo un Cavalliero meglio ponere in essecutione i colpi pensati, & imparati, ove la colera ci impedisce il discorso, leva di se stesso l'huomo, & lo fa operare senza sapere il perche, & il come. | ||

Response to the objection, to wit, that intemperate choler hinders, and the temperate is of use. ROD: If you propose to me a furious choler, that deprives one of intellect and speech, I would not differentiate among a choleric, and a furious, and an unreasoning animal, and then I would say that it would be detrimental, and that it would not suit our proposition. But if it were to be a temperate choler such as completely obscures reason, I tell you that it would be very useful; because choler is a fire of the blood around the heart, which, being temperate, temperately ignites the heart, and in consequence the ignited humors are temperately elevated, so that they give superior agility and force to the motive spirit, and they work more quickly in the function of every sense, and ultimately the speech, and therefore I must say that a little bit of choler is of use to the soldier, as well to whomever would practice in arms. |

[52r.2] ROD. Se voi mi date una colera furiosa, si che lievi l'intelletto, & il discorso; io non farò differenza tra un colerico, & un furioso, & un'animale irragionevole, & all'hora dirò che sia nociva, & che non si ricerchi al proposito nostro. Ma se sarà una colera temperata tale, che oscuri in tutto la ragione; dicovi che serà di molto giovamento: perche la colera è un incendio del sangue circa al core, la quale, sendo temperata accende temperatamente il core, & per consequente temperatamente si inalzano gli spiriti accesi, che danno maggior agilità, & forza all'anima motiva, & fanno piu presto nelle operationi ogni senso, & ultimamente il discorso, & perciò si puo dire, che un poco di colera giovi al soldato, & anco achi vole essercitarsi nell'armi. | ||

Difficulty of doing two mandritti tondi without pause, such that one lands no higher than the other. CON: This is certainly the cause that one day, while exercising with the conte di Mega, rather moved by the fury of choler, I performed two mandritti tondi, the one after the other without any pause, so that I did not elevate one above the other (and indeed you know, Rodomonte, how hard it would be to do it) whereat the conte was amazed, saying that he had never been able to do it, although he had studied all of the strokes of the sword. |

[78v.4] CON. Vi giuro Signore Aluigi, che tal volta mi son trovato si infuriato, che non havrei ceduto al cielo, et in quella caldezza tai colpi mi sono usciti dalle mani, che non li harrebbe fatto (dirò così) con ogni studio suo il valoroso Marte. Voi sapete bene quanto sia difficile il menare dui mandritti tondi l'un dopo l'altro senza indugio alcuno, talche l'uno non si innalzi più dell'altro, et pur giocando alli passati giorni con il CONTE DI MEGA mi vennero fatti, et non sò come; onde il Conte mezo attonito disse; Credo, che siate il Mastro di coloro, che sanno; io mai a' di miei non gli hò possuto fare, et penso che ricercasse tutti i tratti della spada, nè mai gli colse, et è pur [79r.1] Cavallier al pari di ogni altro valoroso, |

[52r.3] CON. Questa fu certo la cagione, che un giorno essercitandomi co'l Signor Conte di Mega, mosso alquanto dal furore della colera; feci due mandritti tondi l'un dopo l'altro senza indugio alcuno, tal che l'uno non s'inalzò piu dell'altro, & pur sapete Rodomonte quanto sia difficile a farli, onde il Conte restò maravigliato dicendo non haverli mai potuto fare anchor che havesse ricercati tutti i tratti della spada. | |

ROD: The conte di Mega marveled at it; still others would be able to marvel well thereat, he being a knight the peer of any other of valor. |

[52r.4] ROD. Maravigliandosene il Conte di Mega, se ne potevano ben maravigliare anchor gli altri, sendo egli Cavalliero al pari d'ogni altro valoroso. | ||

CON: And more still I say to you, that I wish to do it again; I never knew how to find the path to the way to do it one more time; nevertheless much have I wearied myself, much have I thought thereupon, so that I indeed discovered the way of doing it twice successively, but now the cut is not flat. |

[79r.2] et diro vui anchora, ch'io volsi rifarli nè seppi mai ritrovarli modo, nè strada per farli un'altra volta; niente di manco tanto m'affaticai, e tanto vi pensai sopra, che ritrovai pur modo di farne due successivamente, ma di piatto, non gia di taglio. |

[52r.5] CON. Et piu diro vui anchora, ch'io volsi rifarli, ne seppi mai ritrovarli strada ne modo per [52v.1] farli un' altra volta: niente di meno tanto m'affaticai, tanto vi pensai sopra, che ritrovai pure modo di farne due successivamente, ma di piatto non già di taglio. | |

ROD: I would do a hundred of them, not two, in that way; the difficulty is to do them edge on; but now it is time that we begin to practice, before the hour grows later: take up your sword, conte. |

[79r.3] ROD. Io ne farei cento, non che due à quella guisa, o bel tratto, ma già è tempo, che cominciamo ad essercitarsi avanti, che piu tardi l'hora perche cavalcaremo poi un poco col Conte Ugo à riveder Bologna. |

[52v.2] ROD. Io ne farei cento, non che due a quella guisa: la difficultà è a farli di taglio: ma già è tempo che cominciamo ad essercitarci, avanti che piu tardi l'hora: pigliate la spada vostra Conte. | |

[79r.4] CON. Perche non cominciamo? |

|||

[79r.5] RO. da me non manca pigliate la spada vostra. |

|||

With practice weapons, it is not possible to acquire valor nor to learn a perfect schermo. CON: How so, my sword? Isn’t it better to take one meant for practice? |

[79r.6] CON. Come la spada mia? pigliamo le spade da giuoco? |

[52v.3] CON. Come la spada mia? non è meglio pigliar quelle da giuoco? | |

[79r.7] RO. Da gioco? mai non giuocai con quelle armi al tempo di mia vita. |

|||

[79r.8] CO. Per qual cagione? |

|||

ROD: Not now, because with those practice weapons it is not possible to acquire valor or prowess of the heart, nor ever to learn a perfect schermo. |

[79r.9] RO: Perche con quelle armi non si può acquistar valore, ò gagliardia di cuore, nè con esse imparar mai uno Schermo perfetto. |

[52v.4] RO. Non già, perche con quelle arme da giuoco non si può acquistare valore ò gagliardia di cuore, ne con esse imparar mai uno Schermo perfetto. | |

CON: I believe the former, but the latter I doubt. What is the reason, Rodomonte, that it is not possible to learn (so you say) a perfect schermo with that sort of weapon? Can’t you deliver the same blows with that, as with one which is edged? |

[79r.10] CO. La prima vi credo, ma dubito intorno la seconda; qual è la causa Rodomonte, che non si possa imparare, come dicete, un Schermo perfetto con quella sorte d'arme? non menate voi i medesimi colpi con quelle, et con queste da filo? |

[52v.5] CON. La prima vi credo, ma dubito intorno alla seconda. Quale è la causa Rodomonte, che non si possa imparare (come dite) uno Schermo perfetto con quella sorte d'arme? non menate voi i medesimi colpi con quelle, che con queste da filo? | |

Why one cannot learn a perfect blow with practice weapons, but only with those which are edged. ROD: I would not say now that you cannot do all those ways of striking, of warding, and of guards, with those weapons, and equally with these, but you will do them imperfectly with those, and most perfectly with these edged ones, because if (for example) you ward a thrust put to you by the enemy, beating aside his sword with a mandritto, so that that thrust did not face your breast, while playing with spade da marra,[4] it will suffice you to beat it only a little, indeed, for you to learn the schermo; but if they were spade da filo, you would drive that mandritto with all of your strength in order to push well aside the enemy’s thrust. Behold that this would be a perfect blow, done with wisdom, and with promptness, unleashed with more length, and thrown with more force, that it would have been with those other arms. How will you fare, conte, if you take perfect arms in your hand, and not stand with all your spirit, and with all your intent judgment? |

[79r.11] ROD. Non dirò già, che tutti quei modi di ferir, di ripa= [79v.1] rare, & di guardie non facciate con queste, et con quelle parimente, mà le farete con quelle imperfette, et perfettissime in queste da filo |

[52v.6] ROD. Non ditò già che tutti quei modi di ferire, di riparare, & di guardie, non facciate con queste armi, & con quelle parimente, ma le farete con quelle imperfette, & perfettissime con queste da filo: | |

[79v.2] CON. La ragione? |

|||

[79v.3] ROD. Dirolla; se voi fate per essempio riparo alla punta mostratavi dal nemico con ribatter la spada sua con un vostro mandritto, accioche quella punta non vi guardi il petto giocando con spada da marra, basteravui solo di ribatterla un poco, pure che impariate lo Schermo; mà se saranno spade da filo, voi spingerete quel mandritto con tutta la forza vostra per cacciar ben fuore la punta del nemico: Ecco che questo sarà colpo perfetto, fatto con senno, e con prontezza spiccato piu da lunge, e spinto con piu forza, che non saria con quelle altre arme. Come farete, Conte, se pigliarete arme perfette in mano, à non vi star con tutto l'animo, e con tutto il giudicio intento? |

[52v.7] perche se voi fate (per essempio) riparo alla punta mostratavi dal nimico, con ribatter la spada sua con un vostro mandritto, accio che quella punta non vi guardi il petto, giocando con spade da marra; vi basterà solo di ribatterla un poco, pure che impariate lo Schermo: ma se saranno spade da filo, voi spingerete quel mandritto con tutta la forza vostra per cacciar ben fuori la punta del nimico. Ecco che questo sarà colpo perfetto, fatto con senno, & con prontezza, spiccato piu da lunge, & spinto con piu forza, che non sarebbe con quelle altre arme. Come farete Conte, se pigliarete arme perfette in mano, a non vi star con tutto l'animo, & con tutto il giuditio intento? | ||

It is necessary that the warrior remain intent on the point of the weapon of his enemy. CON: Yes, but it is a great danger to train with arms that puncture; if I were to make the slightest mistake, I could do enormous harm. Nonetheless we will indeed do as is more pleasing to you, because you will be on guard not to harm me, and I will be certain to parry, and I will pay constant attention to your point in order to know which blow may come forth from your hand, which is necessary in a good warrior. |

[79v.4] CON. Et di che sorte; ma in fatti àme parte un gran pericolo l'essercitarsi con le armi, che pungono, che s'io facessi un picciol fallo, come andrebbe? |

[52v.8] CON. Sì, ma è un gran perico= [53r.1] lo lo essercitarsi con le arme che pungono: che se io facessi un picciol fallo, potrebbe nocer troppo. | |

[79v.5] ROD. Vi guardarete di no farlo. |

|||

[79v.6] CONT. Si potendo |

|||

[79v.7] ROD. Guarderommi io di non offendervi. |

|||

| [79v.8] CON. Et [80r.1] se la spada vi scappasse ò vi fallisse il colpo? | |||

[80r.2] ROD. Non vi dubbitate, che nell'uno, ne l'altro m'avverria |

|||

[80r.3] CONTE. Et se per mio difetto io ei venissi colto? |

|||

[80r.4] ROD. Serà vostro danno in ultimo. |

|||

[80r.5] CON. Vedete dunque. |

|||

[80r.6] ROD. Credete, Conte, che non haverò l' occhio di continuo alla punta vostra per conoscere qual colpo vi debbia uscir di mano? |

[53r.2] Nondimeno facciamo pur come piu vi aggrada, perche voi guardarete di non mi offendere, & io cercherò di riparare, & starò di continuo intento alla punta vostra per conoscere qual colpo vi possa uscir di mano: | ||

[80r.7] CON. Hareste un buon occhio. |

|||

[80r.8] ROD. Ma Conte, questa è una conditione neccessaria al buon guerriero |

[53r.3] il che è necessario al buon guerriero. | ||

[80r.9] CONTE. Deh per vostra fede Rodomonte pigliamo altre spade che le nostre. Qui sono spade da marra, et queste sono buone. |

|||

Proposition of a schermo which is of a single strike, and a single parry, of a single guard, and in a single time. ROD: Well now, I want to teach to you today a schermo I have never seen to be done by others, and of which I was simultaneously my own tutor and student, which is not to be done otherwise than with good swords, and a single strike, and a single parry, and a single guard; and each of these three things together in a single tempo; with which parry you will be able to ward every sort of blow and offense; and this strike is superior to every other sort of strike, and from this guard every other guard proceeds. |

[80r.10] ROD. Hor sù vi voglio insegnare hoggi uno schermo, che non ho visto mai esser fatto da altri, ilquale però non si fa con altro, che con buone spade. |

[53r.4] ROD. Horsù vi voglio insegnare hoggi uno schermo, che non ho veduto mai esser fatto da altri, & io ne sono stato a me stesso precettore, & discepolo, ilquale però non si fa con altro che con buone spade, | |

[80r.11] CON. Che Schermo è questo? |

|||

[80r.12] ROD. E' un ferir solo, un parar solo, et una guardia sola, et ogni cosa di queste tre insieme è un tempo solo, col qual parato vi possete riparare da ogni sorte di ferire, et di offesa, et questo ferire è superiore ad ogni specie di ferire, et da questa guardia ogni altra guardia procede. |

[53r.5] & è un ferir solo, un parar solo, & una guardia sola; & ogni cosa di queste tre insieme è un tempo solo, co'l qual parato vi potete riparare da ogni sorte di ferire, & di offesa: & questo ferire è superiore ad ogni spetie di ferire, & da questa guardia ogni altra guardia procede. | ||

CON: If thus it is, this seems to me the foundation and base of all this art; indeed the sword has among all the arms the grandest privileges. |

[80r.13] CON. Se cosi è, questo mi par fondamen= [80v.1] to, et base di quest'arte tutta; ma ditemi l' havete imparato da voi stesso, ò pure da altri? |

[53r.6] CON. Se cosi è, questo mi par fondamento & base di tutta questa arte: | |

[80v.2] ROD. Io sono il Precottore, et il discepolo. In fatti la spada ha tra tutte l'arme grandissimi privilegi. |

[53r.7] in fatti la spada ha tra tutte l'arme grandissimi privilegii. | ||

[80v.3] CO. Credo, che sia cosi, et ch'ella fosse la prima ritrovata. |

|||

Prerogatives and praises of the sword. ROD: Of its prerogatives I will leave you to judge, conte. Which is that weapon that can withstand the blows of the sword? What things would you be able to do with any other arm, that you could do with the sword; on the contrary, many parries, and protections, and sorts of strikes you will discover in it, which you cannot easily find in any others; from which it is to be recognized that all of the art consists perfectly in the sword; |

[80v.4] ROD. Delle sue prerogative, ne lascio fare il giuditio à voi. Qual è quell'arme, che dalla spada non pigli i colpi suoi? quante cose voi potete fare con ogn' altr'arme, con essa spada far le potete; anzi molti ripari, schermi, et sorte di ferire ritrovarete in essa, lequali non trovarete cosi agevolmente nelle altre tutte. Donde si conosce, che tutta l'arte perfettamente consiste nella spada. |

[53r.8] ROD. Delle sue prerogative ne lascio fare il giuditio a voi, Conte. Quale è quell'arme che dalla spada non pigli i colpi suoi? Quante cose voi potete fare con ogni altr'arme, con essa spada far le potete: anzi molti ripari, e schermi, & sorti di ferire ritrovarete in essa, iquali non trovarete cosi agevolmente nell'altre tutte: donde si conosce che tutta l'arte perfettamente consiste nella spada: | |

Why the Emperors had the unsheathed sword carried before them. from whence springs the practice that Emperors had borne before them an unsheathed sword, as an emblem of justice, by which they administered, as much as saying that there is no other fitter medium or instrument by which justice may punish the wicked, and defend the good, than by the sword, truly copious in every defense, and in every offense, fine, proper, and an ornament to man. King and Prophet David says in his Psalms, “Gird your sword over your thigh, O Baron, and that will be your ornament, and your splendor.”[5] Did God not have in His hand a sword with which to punish the kings, as is to be read in many places in the Holy Scripture? Did the Angel of the Lord not appear with unsheathed sword in hand to Joshua in Jericho? I would say that in sum the sword is the most perfect, the most agile, the most worthy arm that is to be found, and of greater honor and ornament to the knight, and I believe it may be said that it is the beginning and end of all arms, both offensive and defensive. |

[80v.5] Di qui nasce, che gl' Imperatori si fanno portare dinanzi la spada sfoderata, in segno di Giustitia da essi amministrata, quasi dicendo non esser altro piu atto mezo, od instrumento per la Giustitia in punire gli scelerati, e difensare i buoni di essa spada, veramente copiosa d'ogni difesa, et d'ogni offesa, commoda, destra, e di ornamento all'huomo; dice David ne' Salmi; cinge la spada tua sopra la coscia, ò Barone, Et quella [81r.1] sarà l'ornamento tuo, et lo splendor tuo. Esso Iddio, non tiene la spada in mano per punir i rei? come in molti luoghi della sacrascrittura si legge? l'Angelo di Dio non apparve con la spada sfodrata in mano à Iosuè in Ierico? Dirò che la spada in somma sia la piu perfetta, la piu agile, la piu degna arma, che si ritrovi, e di maggior honore, et ornamento al Cavalliero: et credo si possa dire, ch'ella sia, et principio, e fine di tutte le armi tanto offensive, come difensive. |

[53r.9] di qui nasce che gli Imperatori si fanno portare innanzi la spada sfodrata, in segno di Giustitia, da essi amministrata, quasi dicendo non esser'altro piu atto mezo, od instrumento per la Giustitia in punire gli scelerati, & difensare i buoni di essa spada, veramente copiosa d'ogni difesa, & d'ogni offesa, commoda, destra, & di ornamento all'huomo. Dice David Re, & [53v.1] Profeta ne'salmi suoi, cingi la spada tua sopra la coscia, o Barone, & quella sarà l'ornamento tuo, & lo splendor tuo. Esso Iddio non tiene la spada in mano per punire i rei? come in molti luoghi della Sacra scrittura si legge? l'Angelo di Iddio non apparve con la spada sfodrata in mano a Iosue in Ierico? dirò che la spada in somma sia la piu perfetta, la piu agile, la piu degna arme che si ritrovi, & di maggior honore, & ornamento al Cavalliero: & credo si possa dire, ch'ella sia, & principio, & fine di tutte l'arme cosi offensive come difensive. | |

The sword was the first among arms to be discovered. CON: Do you believe that it was the first discovered? |

[81r.2] CON. Credete, che fosse la prima? |

[53v.2] CON. Credete che fosse la prima ritrovata? | |

Inventor of the sword. ROD: It was certainly the first, and never since abandoned by man; I believe that it had its origin from the first blacksmith, Tubal Cain, son of Lamech by his wife Zilla; will you not observe how many times the sword is named in the Holy Scripture? The sword is the most ancient, conte, and most modern. |

[81r.3] RO. Fu la prima certissimamente, ne mai piu è stata dall' huomo abbandonata. |

[53v.3] RO. Fu la prima certissimamente, ne mai piu è stata dall'huomo abandonata: | |

[81r.4] CON. A'che tempo hebbe origine? |

|||

[81r.5] RO. Credo dal primo Fabbro Tubal Cain, figlivolo di Lamech della moglie Zilla, non vedete quanto nominata sia essa spada nella sacrascrittura? Antichissima fu la spada, Conte, et modernissima. |

[53v.4] credo che hebbe origine dal primo fabro Tubal Cain, figlivolo di Lamech della moglie Zilla; non vedete quanto nominata sia essa spada nella Sacra scrittura? Antichissima su la spada Conte, & modernissima. | ||

Judgment of the ancient single-edged sword. CON: I liked well that ancient sword, to which was given a dull edge[6] on one side, so that it was stronger and safer: you could push the single-edged sword with your left hand also, to deliver the blow more firmly, and if the enemy were to beat it back toward your face, in order to offend you, at least it would not cut your face; if we say, Rodomonte, that it is both to offend and defend, then it may better perform these two tasks if it is of that form. |

[81r.6] CON. Mi piaceano quelle spade antiche assai, à cui davano la costa da un lato accioche piu ferma, e piu sicura fosse. voi potete la spada d'un sol filo spinger con la sinistra mano anchora, per far il colpo piu gagliardo. Et s'avenisse, che'l nimico ve la ri= [81v.1] butasse verso la faccia, se v'offendesse, almeno non vi taglierebbe il viso: si che diciamo, Rodomonte, che questa è per offendere, et per difendere; adunque meglio fà tutte due l'opere in quella forma. |

[53v.5] CON. Mi piacevano quelle spade antiche assai, a cui davano la costa da un lato, accioche piu ferma, & piu sicura fosse: voi potete la spada d'un sol filo spinger con la sinistra mano anchora, per far il colpo piu gagliardo, & s'avenisse che'l nimico ve la ributasse verso la faccia, se v'offendesse; almeno non vi tagliarebbe il viso: si che diciamo Rodomonte che questa è per offendere, & per difendere: adunque meglio fa tutte due l'opere in quella forma. | |

ROD: You do not know, conte, of how much importance the edge of the sword is, and if the enemy then beats back your sword toward your face, it is not a defect of the sword, but of you, that you do not know the art, or that you have too little strength in you; it was indeed safer, but also less able to offend. |

[81v.2] RO. Voi non sapete, conte, di quanta importanza sia il filo, della spada, et s'il nemico poi vi ributta la spada verso la faccia non è difetto della spada ma di voi, che non sapete l'arte, ò che minor forza havete di lui. |

[53v.6] RO. Voi non sapete Conte di quanta importanza sia il filo della spada, & se'l nimico poi vi ributta la spada verso la faccia, non è difetto della spada, ma di voi, che non sapete l'arte, o che minor forza havete di lui: | |

[81v.3] CON. Era pur piu sicura quella. |

[53v.7] era ben piu sicura quella, | ||

[81v.4] ROD. Ma meno anchor offensiva. |

[53v.8] ma meno anchor offensiva. | ||

Judgment of the ancient swords with a dull edge on a side of the half adjacent to the hilt. CON: It was possible to do so in the form of many swords that I have seen, in which the dull edge extends through the entire forte of the sword, which is the half adjacent to the hilt, while the debole of it, which is the half adjacent to the point, has a false and a true edge. |

[81v.5] CON. Si potea farla nella guisa di molte spade, che ho vedute io: nellequali la costa è per tutto il forte della spada, che è dalla meza parte verso l'elzo, et il debole di essa, che è dala meza parte verso la punta havea il falso, et il dritto filo. |

[53v.9] CON. Si potea farla nella guisa di molte spade, che ho vedute io: nelle quali la costa è per tutto il forte della spada, che è dalla meza parte verso l'elzo, & il debole di essa, che è dalla [54r.1] meza parte verso la punta, havea il falso, & il dritto filo. | |

Antiquity of the sword with two edges from the hilt to the point. ROD: It was certainly possible to do it, but the modern usage has rediscovered the most offensive way to be having the entire length of both sides to be sharp edges; because when one comes to the half sword in combat, the false edge of the forte of the sword is quite opportune; think of it, conte: it is very modern to have two edges from the hilt to the point; I would rule that in the time of David they were of this fashion. He says in the Psalms these words: “The highness of God in their mouths, and a double-edged sword in their hand, to inflict vengeance on the nations”;[7] and I discussed with a Hebrew friend of mine in Mantua, that they are understood in the Hebrew language to be written thus as I have said. |

[81v.6] RO. Si potea fare per certo, ma il moderno uso hà ritrovato, che piu offensiva sia havendo da tutti due i lati il taglio, perche quando si viene à meza spada nella pugna dico che è molto à proposito il falso filo del forte della spada, ne vi pensate Conte, che molto moderno sia l'haver due fili dal elzo sino alla punta; impero che al tempo di David ve n'erano di questa maniera; dice [82r.1] egli ne' salmi queste parole? L'altezza d'Iddio nella gola loro, e spada di due fili nella sua mano per far vendetta nelle genti. Et io ragionando con un Hebreo mio amico in Mantova, intesi, che nella lingua hebrea si scrive cosi, come u' hò detto. |

[54r.2] RO. Si potea fare per certo, ma il moderno uso ha ritrovato che piu offensiva sia, havendo da tutti due i lati il taglio: perche quando si viene a meza spada nella pugna, dico che è molto a proposito il falso filo del forte della spada: ne vi pensate, Conte, che molto moderno sia l'haver due fili dall'elzo sin'alla punta: imperò che al tempo di David ve n' erano di questa maniera. Dice egli ne'Salmi queste parole. L'altezza d'Iddio nella Gola loro & spada di due fili nella sua mano, per far vendetta nelle genti; & io ragionando con un Hebreo mio amico in Mantova, intesi che nella lingua Hebrea si scrive cosi come u' hò detto. | |

CON: I have indeed seen that swords have had dull edges for but few days. |

[82r.2] CON. Hò pur vedut'io pochi giorni sono alcune spade con la costa. |

[54r.3] CON. Ho pur veduto io pochi giorni sono alcune spade con la costa. | |

ROD: It is not a long time that those of that style were being used for the most part; also the rediscovery of this sort in these times was but recent; it is the manner in our days that little do we spy of the dull edge. |

[82r.3] ROD. Non è gran tempo, che s'usavano à quel modo per la piu parte, pur se ne trovavano ancora in quei tempi di questa sorte, ma poche; si come adesso à giorni nostri poche ne veggiamo con la costa. |

[54r.4] RO. Non è gran tempo che s'usavano a quel modo per la piu parte: pur se ne ritrovano anchor in quei tempi di questa sorte, ma poche; si come a'giorni nostri poche ne veggiamo con la costa. | |

CON: Were the ancients using, perhaps, hilts with grips like we use? |

[82r.4] CO. Usavan forse gli antichi di far quegli elzi con quelle impugnature, come usiam noi? |

[54r.5] CON. Usavan forse gli antichi di far quegli elzi, con quelle impugnature come usiam noi? | |

Ancient and modern styles of using the hilts. ROD: They certainly used them, except that to them have been joined all the garnishment that you see from pommel to cross, and provide marvelous defense to the hand; some improvement is constantly discovered by modern men. |

[82r.5] RO. L' usavano per certo, eccetto, che u'è stato aggiunto tutto quel guarnimento, che vedete dal Pomo alla Croce, è fa mirabil difesa alla mano; sempre si ritrova da i moderni qualche miglioramento. |

[54r.6] RO. L'usavano per certo, eccetto che u'è stato aggiunto tutto quel guarnimento che vedete dal Pomo alla croce, & fa mirabil difesa alla mano: sempre si ritrova da'moderni qualche miglioramento. | |

CON: Why is the sword carried at the left side? |

[82r.6] CO. Perche si porta la spada dal lato stanco? |

[54r.7] CON. Perche si porta la spada dal lato stanco? | |

Why the sword is carried at the left side. ROD: I don’t know in what other place you would be able to carry it from which you could draw it with less trouble, and in which you would be more prepared if you had need. It does not impede the hands; in that place you are able to promptly place your right hand in order to draw it out; and finally I do not find any site more convenient, and commodious, and that leaves you free and loose of the entire body, than the left side. |

[82r.7] RO. Non sò in qual luogo poteste voi portarla, che vi desse minor noia, e che piu apparecchiata l'haveste al bisogno vostro. Ivi non u'impedisce alcuna delle mani in quel luogo tosto potete porre la destra mano per trarla fuore, e finalmente non trovo sito piu conveniente, et [82v.1] commodo, et che più vi lasci libero, e sciolto della persona tutta, che'l manco lato. |

[54r.8] RO. Non sò in qual luogo poteste voi portarla che vi recasse minor noia, & che più apparecchiata l'haveste al bisogno vostro. Ivi non u'impedisce alcuna delle mani: in quel luogo tosto potete porre la destra mano per trarla fuori, & finalmente non trovo sito piu conveniente, & commodo, & che vi lasci libero, & sciolto della persona tutta che'l manco lato. | |

CON: I have understood some to say that one carries it on that side out of respect that the left side, where the heart lies, is more worthy, and has greater need of defense. |

[82v.2] CO. Hò d'alcuni inteso dire, che si porta da quel lato per rispetto, che la parte sinistra (dove giace il cuore) è piu degna, et piu ha bisogno di difesa. |

[54r.9] CON. Hò da alcuni inteso dire che si porta da quel lato per rispetto, che la parte sinistra, dove giace il cuore; è piu degna, & piu ha bisogno di [54v.1] difesa. | |

Position of the heart in the human body. ROD: This is not a good reason, conte, in my opinion. Firstly, I have seen in anatomy, that the heart does not rest on the left side more so than on the right, but rather in the center of the chest; it is indeed true that the tip leans a little to the left side; but if this were the true reason then left-handed people would also gird it on that side; but that defense of the left side is the reason to carry it on that side? The real reason I believe to be that which I have said, conte, and left-handed people are an indication thereof, that in order to accommodate themselves to draw it forth from their right hand side, they do gird it on their right. |

[82v.3] RO. Questa non è buona ragione, Conte, secondo il mio parere: primieramente non credo, anzi l'ho pur veduto, che'l cuor stia dalla banda sinistra piu che dalla destra; ma stassi nel mezo del petto, è ben vero che la punta si volta un poco verso il lato manco; ma se questa fosse la ragion vera anchora gli huomini mancini se la cingerebbono da quel lato, e poi, che difesa è quella alle parti sinistre per portarla da quel lato destro del fodro? La vera causa è quella, che vi ho detto io, Conte, et ne fanno segno essi mancini, che per farsela piu commoda, è destra al tirarla fuore, la cingono dal diritto lato. |

[54v.2] ROD. Questa non è buona ragione (Conte) secondo il mio parere. Primieramente io ho veduto nelle anotomie, che'l cuore non stà dalla banda sinistra piu che dalla destra: ma stassi nel mezo del petto: è ben vero che la punta si volta un poco verso il lato manco: poi se questa fosse la ragion vera, anchora gli huomini mancini, se la cingerebbon da quel lato: ma che difesa è quella alle parti sinistre per portarla da quel lato? la vera causa credo esser quella che vi ho detto io (Conte) & ne fanno segno essi mancini, che per farsela piu commoda, & destra al trarla fuori, la cingono dal dritto lato. | |

CON: I well believe this to be the actual reason. |

[82v.4] CO. Credo bene, che questa sia la vera cagione. |

[54v.3] CON. Credo bene che questa sia la vera cagione. | |

ROD: You would be well resolved, my conte, to pass this little time in discussions of some small use to us. |

[82v.5] RO. Voi vi siete deliberato di passar questo poco di tempo in cianze; hor prendete anco voi la vostra spada. |

[54v.4] ROD. Voi vi siete deliberato, Conte mio, di passar questo poco di tempo in ragionamenti a noi poco utili. | |

CON: You speak the truth; it is better to turn to actions, because even if these discussions are indeed useful, they may nonetheless be conducted at other times; now wield your sword fancily a bit, please, Rodomonte. |

[82v.6] CO. Ecco, che son contento, et la piglio, hor maneggiate un poco di capriccio, di gratia Rodomonte. |

[54v.5] CON. Dite vero, che è meglio venire a'fatti, perche se bene utili fono questi ragionamenti; si ponno nondimeno fare in altro tempo, hor maneggiate la vostra spada un poco di capriccio di gratia Rodomonte. | |

ROD: Here you are; I do so willingly. |

[54v.6] ROD. Ecco ch'io il faccio volentieri. | ||

On the fancy handling of the sword. CON: Lovely! But how do you accomplish the settling of the sword in your hand after so much, and so many flourishes? |

[83r.2] CO. O' bella; ma come fate voi à rassettarvi quella spada in mano dopo tanti, e tanti avuolgimenti? |

[54v.7] CON. O bella: ma come fate a rassettarvi quella spada in mano dopo tanti, & tanti avuolgimenti? | |

ROD: I cannot describe it to you, conte, but open your eyes well, and pay diligent attention to my wrist, and foremost to the dexterity of the manner of resettling it. Do you see how I do it? Similar actions are to be demonstrated, and to be learned, more and better in proof, and with the sense of sight, than with words; and whoever wanted to express them in words would be in need of that which I know well-- all the muscles of the hand, and the fingers; and I will tell you, that you need to do such and such motion, with this and that muscle, and relax the hand thus, and grip it thus; and he would serve in the role of a good doctor, and a professor of anatomy; because another would not understand it; do these two successive mandritti tondi of yours a bit, conte. |

[83r.3] ROD. Non ve lo posso descrivere, Conte, ma voi aprite ben gli occhi, & ponete diligente cura à i nodi della mano, et alla destrezza del rassettarsela, come vedete, che prima faccio io. |

[54v.8] ROD. Non ve lo posso descrivere, Conte: ma aprite ben gli occhi, & ponete diligente cura a' nodi della mano, & alla destrezza del rassettarsela come prima. Vedete come faccio io? | |

[83r.4] CO. Non veggio nulla; fate di gratia un poco piu adagio. |

|||

[83r.5] RO. Ecco; vedete? |

|||

[83r.6] CO. Bisognarebbe me lo diceste. |

|||

[83r.7] ROD. Non ve lo posso dir con parole. |

[54v.9] similiatti si dimostrano, & s'imparano piu & meglio in prova, & co'l senso del vedere, che con le parole, & a chi volesse esprimerli con parole, | ||

[83r.8] CO.Perche? |

|||

[83r.9] ROD. Saria di bisogno, ch' io sapessi bene quei musculi tutti della mano, e delle dita, e ch'io vi dicessi, bisogna fare il tale, e tal moto con questo, e quel musculo, e snodar la mano cosi, & cosi piegarla: in fatti sarebbe ufficio da un buon Medico, o simili, perche un altro non la capirebbe. |

[54v.10] sarebbe di bisogno, ch'io sapessi bene quei musculi tutti della mano, & delle dita, & ch'io vi dicessi, bisogna fare il tale, & tal moto con questo, & quel musculo, e snodar la mano cosi, & cosi piegarla: & sarebbe uffitio da un buon medico, & professore d'anotomia: perche un'altro [55r.1] non la capirebbe: | ||

[83r.10] CO. In fatti non mi vi posso rassetarre, attendiamo pure ad altro. |

|||

[83r.11] ROD. Fate un poco quei vostri due mandritti tondi insieme. |

[55r.2] fate un poco voi, Conte, quei vostri due mandritti tondi insieme. | ||

CON: Here they are. |

[83r.12] CO Eccoli. |

[55r.3] CON. Eccoli. | |

With the sense of hearing one can recognize that a blow goes flat, although otherwise it is not possible to recognize it. ROD: From the whistle of the sword I hear that they went flat; if they are not good the ear is quick in discerning by the speed of the stroke; don’t you hear the big percussion, and the big reverberation you make in the air, taking a great abundance of it with the flat of the sword? You hear a little less loud, but sharper, whistle, when you do it with the true edge. |

[83r.13] RO. Al fischio della spada sento, che vanno di di piatto, se bene non è si pronto l'occhio in discernergli per la velocità del tratto. |

Co'l senso dell'udito si puo conoscere ch'un colpo sia di piatto, anchor che non si possa conoscerlo. [55r.4] ROD. Al fischio della spada sento che vanno di piatto, se ben non è si pronto l'occhio in discernerli per la velocità del tratto: | |

[83r.14] CO. Et come al fischio? |

|||

|

[83r.15] ROD. Al fischio si; non sentite [83v.1] voi, che gran percossa, e che gran riverberatione fate nell' aria pigliandone gran copia col piatto della spada? sentite un poco voi questo men sonoro, ma piu acuto fischio fatto dal fil dritto. |

[55r.5] non sentite voi che gran percossa, & che gran riverberatione fate nell'aria, pigliandone gran copia co'l piatto della spada? sentite un poco voi questo men sonoro, ma piu acuto fischio, fatto dal fil dritto. | ||

CON: You have great judgment, Rodomonte. |

[83v.2] CO. Havete un gran giuditio Rodomonte. |

[55r.6] CON. Havete un gran giuditio Rodomonte. | |

ROD: It is of some use to have somewhat of letters along with this exercise of ours. |

[83v.3] RO. Egli giova assai l'haver qualche lettere insieme con l'essercitio nostro. |

[55r.7] ROD. Egli giova assai l'haver qualche lettere insieme con l'essercitio nostro. | |

CON: How many strikes do you make? |

[83v.4] CO. Quante spetie di ferire fate voi? |

[55r.8] CON. Quante spetie di ferire fate voi? | |

Three types of strikes: mandritto, rovescio, and punta. ROD: I make three of them: mandritto, rovescio, and punta. |

[83v.5] RO. Ne faccio tre. |

Tre spetie di ferire mandritto, rovescio, e punta. [55r.9] ROD. Ne faccio tre, | |

[83v.6] CO. Et quali? |

|||

[83v.7] RO. Mandritto, rovescio, e punta. |

[55r.10] mandritto, rovescio, & punta. | ||

CON: Isn’t there a falso? |

[83v.8] CO. Non vi è il falso? |

[55r.11] CON. Non v'è il falso? | |

ROD: There is, and it is called “falso” only through being of little moment. |

[83v.9] RO. Si; e s'addimanda falso, solo per esser di poco momento. |

[55r.12] ROD. Vi è, & si domanda falso, solo per esser di poco momento. | |

CON: Do all three of them a bit, please, Rodomonte. |

[83v.10] CO. Fateli un poco tutti tre digratia Rodomonte mio. |

[55r.13] CON. Fateli un poco tutti tre di gratia, Rodomonte mio. | |

ROD: Watch: this is a mandritto, this other is a rovescio, and this is a punta. |

[83v.11] ROD. Ecco: questo è il mandritto; quest'altro è rovescio, et questa è punta. |

[55r.14] ROD. Ecco: questo è mandritto, quest'altro è rovescio, & questa è punta. | |

CON: Where do you leave the fendenti dritti and rovesci, the montante, the mandritto and rovescio sgualembrato, the falso manco and dritto? Where do you leave the stoccata and the imbroccata? You have also not done the mandritto tondo and the rovescio tondo. |

[83v.12] CO. Dove lasciate i fendenti dritti, e rovesci, il montante, il mandritto, et il rovescio sgualembrato, il falso manco, et diritto? Dove lasciate la stoccata, e l'imbroccata; altro non havete fatto, che il mandritto tondo, et il rovescio tondo. |

[55r.15] CON. Dove lasciate i fendenti dritti, & rovesci, il montante, il mandritto, & il rovescio sgualembrato, il falso manco, & dritto? dove lasciate la stoccata, & l'imbroccata? altro non havete fatto che'l mandritto tondo, & il rovescio tondo. | |

Which is the true and the false edge. ROD: You know well what is the true and the false edge, that having the double-edged sword by your hip, that edge which is facing more toward the ground is called the true edge, and that which is toward your upper body, facing the sky, is called the false; |

[83v.13] ROD. Voi sapete bene, che cosa è dritto filo, e falso filo, non è egli il vero? |

Qual sia dritto, & falso filo. [55r.16] ROD. Voi sapete bene che cosa è dritto filo, & falso filo, | |

|

[83v.14] CO. Tenendo la spada di due tagli al fianco; quel taglio, che più guarda verso terra, si chiama dritto filo, e quello che verso le parti alte del corpo riguarda verso l'aria, chia= [84r.1] masi falso. |

[55r.17] che tenendo la spada di due tagli al fianco, quel taglio che piu guarda verso terra si chiama dritto filo, & quello che verso le parti alte del corpo, riguarda verso l'aria, chiamasi falso: | ||

Why they are called the true and the false edge. and the reason is this: that throwing a mandritto, or a rovescio, the sword always falls naturally with that edge. I say therefore that there are no other types of strikes than these said three, that can not be classified as one of them; because all those blows that initiate from the right side of the body, |

[84r.2] RO. Benissimo, et la ragion è questa, che tirando un mandritto, ò un rovescio la spada sempre cala naturalmente con quel taglio; dico adunque, che altra specie di ferire diverso da questò tre detti non vi è, che sotto qualch'una di esse non si contenga: |

Perche si chiami dritto, & falso filo. [55r.18] & la ragion è questa, che tirando un mandritto, o un rovescio; la spada sempre cala naturalmente con quel taglio. Dico dunque che altra spetie di ferire diverso da questi tre detti, non vi è, che sotto qualch'una di esse non si contenga: | |

Which are called mandritti. both with the right forward and with the left, are all to be called mandritti, having their origin from the right side, whether from top to bottom, or bottom to top; and these blows have their endings on the left side. See you, conte, that the tondo mandritto, as well as the sgualembrato, together with the falso dritto, should be included under the name of “dritto”; |

[84r.3] perche tutti quei colpi, che nasceranno dalle destre parti della persona tanto co'l pie destro innanzi, quanto con sinistro tutti si addimanderanno mandritti havendo il principio loro dalle diritte parti, cosi da alto al basso, come da basso ad alto, et havranno il lor fine questi tai colpi nelle sinistre parti. Eccovi Conte, che tanto il tondo mandritto quanto lo sgualembrato, et il falso dritto insieme sotto nome di dritto saranno rinchiusi; |

Quali si dimandino mandritti. [55r.19] perche tutti quei colpi che nasceranno dalle parti destre della persona, tanto co'l pie destro innanzi, quanto co'l [55v.1] sinistro, tutti si domanderanno mandritti, havendo il principio loro dalle dritte parti, cosi da alto a basso; come da basso ad alto; & havranno il lor fine questi tai colpi nelle sinistre parti. Eccovi Conte, che tanto il tondo mandritto, quanto lo sgualembrato, & il falso dritto insieme, sotto nome di dritto, saranno rinchiusi, | |

Which are rovesci. and all those blows that originate from the left side of the body and terminate on the right side, both from high to low as well as from low to high, should be called “rovesci”. Under the rovescio therefore are classified the rovescio tondo, the sgualembrato, and the falso manco; and it is called “rovescio” because it springs from the corner opposite from the dritto. |

[84r.4] e tutti quei colpi, che haveranno origine dalla parte sinistra della vita, e finiranno nelle destre parti tanto da alto à basso, quanto da basso ad alto, chiamerannosi rovesci; sotto il rovescio adunque si contiene il rovescio tondo, lo sgualembrato, et il falso manco, et dicesi rovescio, perche egli è nato dal canto rovescio del dritto. |

Quali siano rovesci. [55v.2] & tutti quei colpi che havranno origine dalla parte sinistra della vita, & finiranno nelle destre parti, tanto da alto à basso, quanto da basso ad alto, chiamerannosi rovesci. Sotto il rovescio dunque si contiene il rovescio tondo, lo sgualembrato, & il falso manco; & dicesi rovescio, perche egli è nato dal canto rovescio del dritto. | |

CON: Where do you place the fendenti dritti and rovesci, and the montante? |

[84r.5] CO. Dove riporrete voi i fendenti dritti, et rovesci, et il montante? |

[55v.3] CON. Dove riporrete voi i fendenti dritti, & rovesci, & il montante? | |

It appears that the fendente and the montante should differ from the rovescio. ROD: I do not differentiate them from mandritti and rovesci. |

[84r.6] ROD. Non gli faccio differenti da i mandritti, et rovesci. |

Pare che

siano diversi

il

fendente,

& il montante,

dal

rovescio. [55v.4] RO. Non li faccio differenti da' mandritti, & rovesci. | |

CON: How not? Tell me: are the mandritti not begun on the right side, and the rovesci on the left? And the fendenti from high to low with the true edge, or alternately from low to high? |

[84r.7] CO. [84v.1] Come nò; ditemi i mandritti non nascono dalle parti destre, et i rovesci dalle manche, et essi fendenti da alto à basso per dritto filo, overo da basso ad alto? |

[55v.5] CON. Come no? Ditemi: i mandritti non nascono dalle parti destre, & i rovesci dalle sinistre? & essi fendenti da alto a basso per dritto filo, ò vero da basso ad alto? | |

Three types of strikes derived from three dimensions of continuous quantity. ROD: You maintain that I do not know that obvious argument, conte, for although the fendenti descend or ascend through a straight line, it appears possible to denominate them as being more from the right than the left side; and in addition, there is this more forceful argument: that there are three dimensions: height, width, and depth; it appears that the mandritti and rovesci terminate in width; the thrust of the point, and its withdrawal, terminate in depth; it is accordingly just that the fendenti, and those that you call montanti, terminate in height; and that as these differences of position are varied, thus are these blows also varied; |

[84v.2] RO. Havete non so che d'apparente ragione, Conte, conciosia che per moto retto discendano i fendenti, overo ascendano, ne par, che si possino denominare piu dalle destre, che dalle sinistre parti; et in oltre vi è poi questa piu efficace ragione, che facendosi tre misure, longhezza, larghezza, e spessezza, per dir cosi, par, che i mandritti, et rovesci siano termini della larghezza; il cacciar della Punta, et il tirarla, termini della spessezza: giusta cosa adunque sarà, che i fendenti, et questi vostri chiamati montanti fossero termini della longhezza, e che come le differenze di positione sono varie, cosi fossero anco questi colpi vari, |

Tre specie di ferire tolte dalle tre misure della quantità continua. [55v.6] RO. Havete non sò che d'apparente ragione (Conte) conciosia che per moto retto discendano i fendenti ò vero ascendano; ne par che si possano denominare piu dalle destre, che dalle sinistre parti; & in oltre vi è poi questa piu efficace ragione, che facendosi tre misure, lunghezza, larghezza; & profondità, par che i mandritti, & rovesci, siano termini della larghezza, il cacciar della punta, & il tirarla, termini della profondità: giusta cosa dunque sarà che i fendenti, & questi vostri chiamati montanti, siano termini della lunghezza, & che come le differenze di positione, sono varie, cosi fossero anco questi colpi vari: | |

Regarding nature there may be four kinds of strikes. whence, my conte, regarding nature there may be four types of blows: mandritto, rovescio, fendente, and punta; but we are not considering blows other than those of the sword worn at the hip; we discover therein but those three. |

[84v.3] la onde, Conte mio generoso, in quanto alla natura sariano forse quattro spetie di ferire, Mandritto, rovescio, fendente, et Punta; ma non considerando noi i colpi da altro, che dalla spada al fianco non ritroviamo altri, che quelli tre. |

In quanto alla natura sariano quattro spetie di ferire. [55v.7] la onde (Conte mio) in quanto alla natura sarebbono forse quattro spetie di ferire, Mandritto, Rovescio, Fendente, & Punta: ma non considerando noi i colpi da altro, che dalla spada al fianco; non ritroviamo altri, che quelli tre. | |

CON: How? |

[84v.4] CO. Come? |

[55v.8] CON. Come? | |

There are only three kinds of strikes, considering those had by the sword at the hip. ROD: I will explain it: if you find for yourself your sword at your hip, laying hand to sword teaches you the mandritto, moving your hand from your right, located on the grip of the sword, toward your left side; unsheathing the sword teaches you the rovescio, drawing it from the left to the right side. Seeing that you have fury, make it to be that the point of your sword is aimed at the breast or the face of your enemy; whereupon from putting your hand to your sword, and drawing it, and setting yourself in place against your enemy, you derive these three natural blows; from here you cannot, conte, derive the high to low fendente, or the low to high. |

[84v.5] ROD. Dirollo; se vi ritrovarete la spada [85r.1] al fianco, il metter mano alla spada v'insegna il mandritto movendo la mano dal suo destro sito all'impugnadura della spada nello stanco lato; lo sfoderar della spada v'insegna il rovescio, tirandola dallo stanco al dritto lato; tratta che l'havete fuore, ritrouarete la punta della spada vostra, che riguarda il petto ò la faccia del nimico; dove dal metter mano alla spada, e trarla fuore e rassettarvi verso il nemico voi cavate questi tre colpi naturali; di qui non potete, conte, cavare il fendente d'alto à basso, ò da basso ad alto, |

Tre sono solamente le spetie del ferire, considerando le dall' haver la spada al fianco. [55v.9] RO. [56r.1] Dirollo: se vi ritrovarete la spada al fianco; il metter mano alla spada vi insegna il mandritto, movendo la mano dal suo destro sito all'impugnatura della spada nello stanco lato: lo sfodrar della spada v'insegna il rovescio, tirandola dallo stanco al dritto lato. Tratta che l'havete fuori, ritrouarete la punta della spada vostra, che risguarda il petto, ò la faccia del nimico: dove dal metter mano alla spada, & trarla fuori, & rassettarvi verso il nimico; voi cavate questi tre colpi naturali: di qui non potete (Conte) cavare il fendente d'alto a basso, ò da basso ad alto. | |

Which is punta dritta, and which rovescia. Concerning the third strike, called “punta”, if the punta issues from the right side, it will be called punta rovescia,[8] and if it issues then from high to low, or from low to high, and thus whether its ending is on the left side or the right, all will be under the name of “punta”; it appears to me that having demonstrated to you in full through such reasons, there are only three main types of blows in our art; yet placing the mandritto fendente under the mandritto, and the fendente rovescio under the rovescio, gives force that each blow originates from the right or from the left side. |

[85r.2] quanto al terzo ferir chiamato punta, se nascerà la punta dalle parti diritte chiamerassi punta dritta, se dalle stanche chiamerasse punta rovescia, et nasca poi d'alto à basso, ò da basso ad alto, et cosi sia il suo fine ò alle stanche parti, o alle diritte tutte saranno sotto il nome di punta; si che parmi d'havervi dimostrato à pieno per qual cagione solo tre spetie principali sieno i colpi dell'arte nostra, ponendo però il mandritto fendente sotto il mandritto, et il fendente rovescio sotto il rovescio, sendo forza ch'ogni colpo nasca dal dritto ò dal stanco lato. |

Qual sia puta dritta, & qual rovescia. [56r.2] Quanto al terzo ferire, chiamato punta, se nascerà la punta dalle parti dritte, chiamerassi punta rovescia: & nasca poi da alto à basso, ò da basso ad alto, & cosi sia il suo fine, ò alle stanche parti, ò alle diritte; tutte saranno sotto il nome di punta: si che parmi d'havervi dimostrato a pieno per qual cagione, solo tre spetie principali siano i colpi dell'arte nostra; ponendo però il mandritto fendente sotto il mandritto, & il fendente rovescio sotto il rovescio, sendo forza ch'ogni colpo nasca dal dritto, ò dallo stanco lato. | |

CON: I prefer that argument of yours, according to which the fendenti naturally form another major and distinct type. |

[85r.3] CON. Più [85v.1] mi piacerebbe quella vostra ragione per laquale naturalmente fate essi fendenti un'altra principal spetie, e diversa. |

[56r.3] CON. Più mi piacerebbe quella vostra ragione, per la quale naturalmente fate essi fendenti un'altra principale spetie, & diversa. | |

Whosoever would derive the types of blows from the dimensions and ends thereof, sets there to be three or six in number. ROD: Returning to that argument, either there would be three types or six; because if you would consider only the three dimensions, there would be three: dritto, fendente, and punta; but if you consider the six ends of the three dimensions of space, there would be six: mandritto and rovescio, fendente descendente and fendente ascendente, and thrusting the punta and withdrawing it. |

[85v.2] ROD. Quanto à quella ragione anchora, ò che sariano tre le spetie, ò sei; perche se consideraste solo le tre dimensioni, sariano tre, dritto, fendente, et punta; ma se consideraste i sei fini di esse tre dimensioni, ò spacii sariano sei, mandritto, et rovescio, fendente, descendente, et fendente ascendente cacciar di punta, e ritrarla. |

Chi vol prendere le spetie del ferire dalle dimensioni, & termini della quantità ponno essere treet sei. [56r.4] ROD. Quanto à quella ragione anchora, ò che sarebbono tre le spetie, o sei: perche se consideraste solo le tre dimensioni, sarebbono tre, dritto, fendente, & punta: ma se consideraste i sei fini di esse tre dimensioni ò spatii, sarebbono sei, mandritto, & rovescio, fendente descendente, & fendente ascendente, cacciar di punta, & ritrarla. | |

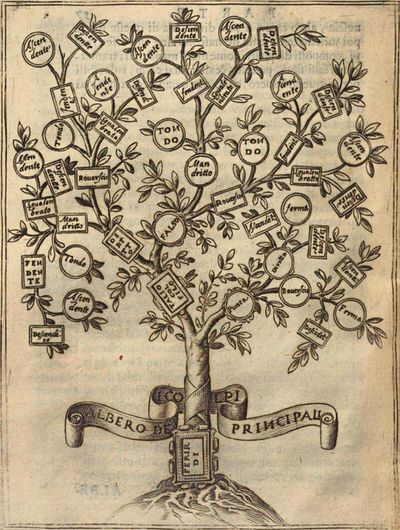

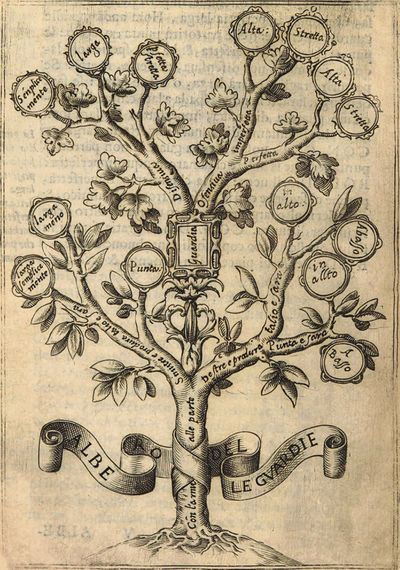

CON: No, no, let us follow the common way: you know what I want from you, Rodomonte: that you make me something like a tree of all these general and particular blows, and make of them an orderly division. |

[85v.3] CO. Nò nò, seguitiamo pur la via commune; sapete che cosa vorrei,sapete che cosa vorrei da voi Rodomonte? |

[56r.5] CON. Nò nò, seguitiam pur la via commune: sapete che cosa vorrei da voi Rodomonte; | |

[85v.4] RO. Che? |

|||

[85v.5] CO. Vorrei, che mi faceste come un Albero di tutti questi generali, e particolari colpí, e farne un partimento regolato. |

[56r.6] che voi mi faceste come un'albero di tutti questi generali, & particolari colpí, & farne [56v.1] un partimento regolato. | ||

|

Tree of Principal Blows |

Division of the family of strikes into types according to their differences. I am happy to do this welcome thing for you; accordingly I tell you that the first family will be the strike. The strike can be of two sorts, either the cut or the thrust. The cut is either with the true edge of the sword or with the false edge. |

[85v.6] ROD. Per farvi cosa grata son contento; onde vi dico, che il primo genere sarà esso ferire. il ferire può esser di due sorti, ò di taglio, ò di Punta; il taglio ò con il dritto fil di essa spada, ò con il falso filo; |

Divisione del genere del ferire nelle sue spetie per le differenze. [56v.2] ROD. Per farvi cosa grata; son contento: onde vi dico, che'l primo genere sarà esso ferire. Il ferire puo essere di due sorti, o di taglio, o di punta. Il taglio, o co'l diritto filo d'essa spada, o co'l falso filo. |

The blows with the true edge are of two types, mandritto and rovescio; the mandritto can be tondo, fendente, and sgualembrato, depending on how the edge falls; if simply from high to low, it will be called “fendente discendente dritto”; if it rises from low to high, it will be called “fendente ascendente dritto”; if the true edge cut goes from the right to the left side, it will be called “mandritto tondo”; if it should go sgualembro, that is, that it begins high and ends low, and simultaneously from the right to the left side, they will call it “mandritto sgualembrato”; if, on the other hand, it goes from low to high, it will be a “sgualembrato ascendente”, which, however, is composed of the tondo and of the fendente. |

[85v.7] il ferire con dritto filo ha sotto di se due specie, mandritto, et rovescio; il mandritto può esser tondo, fendente, et sgualembrato, secondo, che cade il filo, se d'alto à basso semplicemente si chiamerà fendente discendente dritto; se montarà da basso ad alto chiamerassi fendente asce= [86r.1] dente dritto; s'el taglio pel dritto andarà dal destro al sinistro lato chiamerassi mandritto tondo: se caminerà di sgualembro, cio è, che cominci d'alto, e finisca à basso, et insieme dal destro al sinistro lato, lo chiamano mandritto sgualembrato, se pel contrario, da basso ad alto sia sgualembrato dritto ascendente, il quale pero è composto del tondo, e del fendente |

Spetie del ferire co'l dritto filo. [56v.3] Il ferire con dritto filo ha sotto di se due spetie, mandritto, & rovescio: il mandritto puo esser tondo, fendente, & sgualembrato, secondo che cade il filo: se d'alto a basso semplicemente, si chiamerà fendente discendente dritto: se montarà da basso ad alto; chiamerassi fendente ascendente dritto: se il taglio per lo dritto andarà dal destro al sinistro lato; chiamerassi mandritto tondo: se caminerà di sgualembro, cioè che cominci d'alto, & finisca a basso, & insieme dal destro al sinistro lato; lo chiameranno mandritto sgualembrato: se per lo contrario da basso ad alto; sarà sgualembrato ascendente: ilquale però è composto del tondo, & del fendente. | |

There are as many types of strikes with the true edge as there are with the false. These are the types of the mandritto. The rovescio has as many other types, and not more; and if one would strike with the false edge, there are born therefrom as many kinds of strikes as with the true edge, except that you need to add the designation of “falso” to all the particular names, saying “falso mandritto”, “falso rovescio”, “falso mandritto tondo”, “falso mandritto sgualembrato”, “falso fendente”, and thus with all the others from side to side, adding to each this designation of “falso”. |

[86r.2] queste; sono specie del mandritto. Il rovescio ha altre tante specie, e non piu. Et se si ferirà col falso filo ne nasceranno altretante specie di ferire, quanto col dritto filo, eccetto che vi si aggiongerà questo nome di falso à tutti. I particolari nomi dicendo, falso mandritto, falso rovescio, falso mandritto tondo, falso mandritto sgualembrato, falso fendente, e cosi di tutti gli altri à parte à parte giungendovi questo nome di falso. |

Quante sono le spetie del ferire co'l dritto filo tante sono quelle del ferire co'l falso. [56v.4] Queste sono le spetie del mandritto. Il rovescio ha altre tante spetie, & non piu: Et se si ferirà co'l falso filo; ne nasceranno altre tante spetie di ferire, quante co'l dritto filo, eccetto che vi si aggiungerà questo nome di falso a tutti i particolari nomi, dicendo, falso mandritto, falso rovescio, falso mandritto tondo, falso mandritto sgualembrato, falso fendente, & cosi di tutti gli altri a parte a parte, aggiungendovi questo nome di falso. | |

Types of strikes with the point. If one would strike with the point, either it will begin from the right side, and will be called “punta diritta”, or from the left side, and will be called “punta rovescia”;[9] the punta diritta either drops from high to low, and will be called “punta diritta discendente”, or goes from low to high, and will be called “punta diritta ascendente”, or alternately “stoccata”, terminating then on either the right side or the left; or it will go straight ahead, and is called “punta ferma diritta”; of the punta rovescia, there are as many others that can be spoken of. However, if you mix together these types, there are born thereof other imperfect blows, made up of these, such as mezi mandritti, tramazzoni, false feints, jabs, and plenty of other blows, reducible nonetheless to this Tree, which I now present to you for your gratification. |

[86r.3] Se si ferirà con la punta, ò nascerà dalle parti diritte e chiamerassi punta diritta, ò dalle parti stanche, e chiamerassi punta rovescia: la punta diritta ò cala d'alto à basso e chiamerassi punta diritta discendente, ò da basso ad alto e chiamerassi punta dritta ascendente, overo stoccata, finisca poi dal destro lato ò dallo stanco, ò che va drittamente, e chiamasi [86v.1] punta ferma diritta; della punta rovescia, altre tanto si puo dire. Ma di queste specie poi mischiate insieme ne nascono altri imperfetti colpi composti di questi, come mezi mandritti, tramazzoni, falsi finti, puntati, et altri assai colpi riducibili pero à questo albero ch'io per compiacervi hora vi descrivo. |

Spetie lel ferire con punta. [56v.5] Se si ferirà con la punta, o nascerà dalle parti diritte, & chiamerassi punta diritta, o dalle parti stanche, & chiamerassi punta rovescia: la punta diritta, o cala da alto a basso, & chiamerassi punta diritta discendente, o da basso ad alto, & chiamerassi punta diritta ascendente, overo stoccata, finisca poi dal destro lato, o dallo stanco: o che và dirittamente, & chiamasi punta ferma diritta: della punta ro= [57r] vescia, altro tanto si può dire. Ma di queste spetie poi mischiate insieme ne nascono altri imperfetti colpi, composti di questi, come mezi mandritti; tramazzoni, falsi finti, puntati, & altri assai colpi, riducibili però à questo Albero, ch'io per compiacervi hora vi descrivo. | |

Objection as to whether there should be only two principal strikes: cut and thrust. CON: According to this profound distinction of yours, it appears to me that this first division of the three types, namely, mandritto, rovescio, and punta, is not convenient; because the mandritto and rovescio are two prime types derived from the straight edge; and the thrust, which you have divided, contrasts the cut, so that it appears that there are only two principals: thrust, and cut. |

[86v.2] CO. Secondo questa vostra profonda distintione mi pare che quella prima delle tre specie, cioè mandritto rovescio, e punta non sia conveniente: perche il mandritto, e rovescio sono due specie prime del diritto filo: et la punta c'havete divisa voi contra il taglio, talche pare, che siano solamente due principii, Punta, e taglio. |

Dubitatione

che siano

solamente

due principii

di ferire

taglio,

&

punta. [58r.1] CON. Secondo questa vostra profonda distintione; mi pare che quella prima delle tre spetie, cioè mandritto, rovescio, & punta, non sia conveniente: perche il mandritto, & rovescio sono due spetie prime del diritto filo, & la punta che havete divisa voi, contra il taglio; tal che pare che siano solamente due principii; Punta & taglio. | |

Refutation of the objection. ROD: This is a most lovely objection, to which I respond, that I made those three types (mandritto, rovescio, and punta) the principal ones, making such divisions from putting the hand to the sword (as I told you), and not according to the nature of the blows, or of the sword, or of the location, or dimensions. |

[86v.3] ROD. Questa è una bellissima dubitatione alla quale rispondo, che feci quelle tre specie, mandritto, rovescio, et punta principali facendo tal divisione dal metter mano alla spada (come vi dissi) ma non secondo la natura de i colpi, e della spada, e del sito, e delle dimensioni. |

Solutione della dubitatione. [58r.2] ROD. Questa è una bellissima dubitatione, alla quale rispondo, che feci quelle tre spetie, mandritto, rovescio, & punta, principali, facendo tal divisione dal metter mano alla spada (come vi dissi) ma non secondo la natura de'colpi, & della spada, & del sito, & delle dimensioni. | |

[86v.4] CON. Puo esser questo, che siate tanto valente Signor Rodomonte? |

|||

[86v.5] ROD. Sono tale come mi vedete alli piaceri vostri, Conte gentile. |

|||

CON: Tell me a bit, which of these three types of blows of yours holds the first place? |

[86v.6] CO. Vi ringratio Signor ma ditemi un poco qual [87v.1] è di quelle vostre tre spetie di ferire, che tenga il primo luogo? |

||

Ranking of nobility among the types of strikes. ROD: I believe that the first would be the punta, and after that the rovescio, and then the mandritto. |

[87v.2] ROD. Credo che prima sia la punta. |

Ordine in nobiltà tra le spetie di ferire. [58r.4] ROD. Credo che prima sia la punta, | |

[87v.3] CO. et dopo essa? |

[58r.5] & dopo essa | ||

[87v.4] ROD. il rovescio |

[58r.6] il rovescio, | ||

[87v.5] CO. Et poi il mandritto. |

[58r.7] & poi il mandritto. | ||

[87v.6] RO. Cosi è. |

|||

CON: And I maintain the exact opposite. Because it seems to me that the mandritto is more noble, more natural, and more proper, and after that its opposite, the rovescio, and finally the punta; and for what reason do you assign your order? |

[87v.7] CO. Per mia fe ch'io tenea tutto il contrario. |

[58r.8] CON. Et io tenea tutto il contrario. | |

[87v.8] RO. Per qual cagione? |

|||

[87v.9] CON. Che sò io; parmi che il mandritto sia piu nobile, piu naturale, e piu destro, e dopo esso il suo contrario rovescio; ultimatamente essa punta. Et voi che ragione assignate all'ordine vostro? |

[58r.7] Perche parmi che'l mandritto sia piu nobile, piu naturale, & piu destro, & dopo esso il suo contrario rovescio, ultimamente, essa punta: & voi che ragione assegnate all'ordine vostro? | ||