|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Nicoletto Giganti"

| Line 186: | Line 186: | ||

| <p>Now, in order to come to what I promised above about this noble science, I will go over its qualities and nature, discussing whether it is speculative or practical science. I say that, in my opinion, it is speculative, and prove it with diverse reasons. There is no doubt that it is science because it is not acquired if not through the operation of the intellect, from which it springs. That it is speculative is certain, as it does not consist in more than the simple knowledge of its object, as I will further demonstrate below.</p> | | <p>Now, in order to come to what I promised above about this noble science, I will go over its qualities and nature, discussing whether it is speculative or practical science. I say that, in my opinion, it is speculative, and prove it with diverse reasons. There is no doubt that it is science because it is not acquired if not through the operation of the intellect, from which it springs. That it is speculative is certain, as it does not consist in more than the simple knowledge of its object, as I will further demonstrate below.</p> | ||

| − | <p>The object of this science is nothing more than parrying and wounding. The knowledge of those two things is a work of the intellect, and experts of this science do not with intelligence extend it further than the knowledge of them. They cannot be understood at all unless one first has knowledge of tempi and measures, nor feints, disengages, or resolutions without knowledge of tempi and measures. These are all operations of the intellect. Moreover, the intellect does not reach beyond this understanding because, as I have said, the aim of this profession is understanding parrying and wounding. We will see whether it is real speculative or rational speculative science, however.</p> | + | <p>The object of this science is nothing more than parrying and wounding. The knowledge of those two things is a work of the intellect, and experts of this science do not with intelligence extend it further than the knowledge of them. They cannot be understood at all unless one first has knowledge of ''tempi'' and measures, nor feints, disengages, or resolutions without knowledge of ''tempi'' and measures. These are all operations of the intellect. Moreover, the intellect does not reach beyond this understanding because, as I have said, the aim of this profession is understanding parrying and wounding. We will see whether it is real speculative or rational speculative science, however.</p> |

| − | <p>Thinking on this, it cannot be rational, and the reason is this: Even though it is an operation of the intellect, it nevertheless extends further, wherefore I find it to be real speculative science. Real, because the knowledge of its aim is shown to us outwardly by the intellect, since the understanding of wounding and parrying, along with tempi, measures, feints, disengages, and resolutions, despite being operations of the intellect, cannot be understood if outwardly. This outward expression consists in the bearing of the body and sword in the guards and counterguards, which all consist of circles, angles, lines, surfaces, measures, and of numbers.</p> | + | <p>Thinking on this, it cannot be rational, and the reason is this: Even though it is an operation of the intellect, it nevertheless extends further, wherefore I find it to be real speculative science. Real, because the knowledge of its aim is shown to us outwardly by the intellect, since the understanding of wounding and parrying, along with ''tempi'', measures, feints, disengages, and resolutions, despite being operations of the intellect, cannot be understood if outwardly. This outward expression consists in the bearing of the body and sword in the guards and counterguards, which all consist of circles, angles, lines, surfaces, measures, and of numbers.</p> |

<p>These things, which must be observed, can be read about in Camillo Agrippa and in many other experts of this science. Note that, just as those operations of the intellect without an exterior operation cannot be shown, so these exterior operations cannot be understood without the prior operations of the intellect, in a way that this science, which derives from the intellect, cannot be understood if not outwardly. Neither can it be outwardly understood without operations of the intellect. These operations seek to understand the greatness, excellence, and perfection of this profession, and will always be seen united. As there will never be sun without day, nor day without sun, never will there be those without these, nor these without those. In the end we see that it is real speculative science.</p> | <p>These things, which must be observed, can be read about in Camillo Agrippa and in many other experts of this science. Note that, just as those operations of the intellect without an exterior operation cannot be shown, so these exterior operations cannot be understood without the prior operations of the intellect, in a way that this science, which derives from the intellect, cannot be understood if not outwardly. Neither can it be outwardly understood without operations of the intellect. These operations seek to understand the greatness, excellence, and perfection of this profession, and will always be seen united. As there will never be sun without day, nor day without sun, never will there be those without these, nor these without those. In the end we see that it is real speculative science.</p> | ||

| − | <p>This science of the sword, or of arms, is a real speculative mathematical science—of geometry, and arithmetic. Of geometry because it consists in lines, circles, angles, surfaces, and measures, and of arithmetic because it consists in numbers. There is no motion of the body that does not produce an angle or constraint, no motion of the sword that does not travel in a line, no guard or counterguard that does not proceed by number. The observations of these things all depend on knowledge of tempi and measures, whence I conclude that this most noble science is speculative real mathematical—of geometry and arithmetic—as I said a little above.</p> | + | <p>This science of the sword, or of arms, is a real speculative mathematical science—of geometry, and arithmetic. Of geometry because it consists in lines, circles, angles, surfaces, and measures, and of arithmetic because it consists in numbers. There is no motion of the body that does not produce an angle or constraint, no motion of the sword that does not travel in a line, no guard or counterguard that does not proceed by number. The observations of these things all depend on knowledge of ''tempi'' and measures, whence I conclude that this most noble science is speculative real mathematical—of geometry and arithmetic—as I said a little above.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/12|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/13|1|lbl=ix|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/12|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/13|1|lbl=ix|p=1}} | ||

| Line 213: | Line 213: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>We have therefore seen that it is a science and that it is mathematics—of geometry and arithmetic—since it consists in numbers, lines, and measures. The author does not make mention of this in his observations so that learned persons and those with no study may acquire some profit from him. From these figures and his renowned lessons, therefore, without learning to understand the multiplicity of lines, circles, angles, and surfaces which would instead confuse the mind of the reader that does not understand these studies, giving him no instruction, everyone will without doubt or effort learn to understand tempi, measures, resolutions, feints, disengages, and the method of parrying and wounding.</p> | + | | <p>We have therefore seen that it is a science and that it is mathematics—of geometry and arithmetic—since it consists in numbers, lines, and measures. The author does not make mention of this in his observations so that learned persons and those with no study may acquire some profit from him. From these figures and his renowned lessons, therefore, without learning to understand the multiplicity of lines, circles, angles, and surfaces which would instead confuse the mind of the reader that does not understand these studies, giving him no instruction, everyone will without doubt or effort learn to understand ''tempi'', measures, resolutions, feints, disengages, and the method of parrying and wounding.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/14|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/14|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|9|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|9|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 356: | Line 356: | ||

| <p>[1] '''Guards and Counterguards'''</p> | | <p>[1] '''Guards and Counterguards'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>It is necessary for someone wishing to become an expert on the science of arms to understand many things. To give my lessons a beginning, I will first begin to discuss guards and counterguards, or postures and counterpostures, of the sword. This because, coming to some incident of contention, it is first necessary to understand this to be able to secure oneself against the enemy. To position oneself in guard, therefore, many things must be observed, as seen in my figures: Standing firm over the feet, which are the base and foundation of the entire body, in a just pace, restrained rather than long in order to be able to extend, holding the sword and dagger strongly in the hands, the dagger now high, now low, now extended, the sword now high, now low, now on the right side, in place in order to parry and wound so that the enemy, throwing either a thrust or cut, can be parried and wounded in the same ''tempo'', with the vita disposed and ready because lacking its disposition and readiness it will be an easy thing for the enemy to put it into disorder with a ''dritto'', a ''riverso'', a thrust, or in some other manner, and even if such a person were to parry, they would remain in danger. It is advised that the dagger should guard the enemy’s sword because if the enemy throws, it will parry that, and that the sword should always aim at the uncovered part of the enemy so that he is wounded when throwing. This is all the artifice of this profession. Moreover, it must be noted that all motions of the sword are guards to those who know them, and all guards are good for the practised person, as, on the contrary, no motion is a guard to those who do not understand any, and they are not good for those who do not know how to use them.</p> | + | <p>It is necessary for someone wishing to become an expert on the science of arms to understand many things. To give my lessons a beginning, I will first begin to discuss guards and counterguards, or postures and counterpostures, of the sword. This because, coming to some incident of contention, it is first necessary to understand this to be able to secure oneself against the enemy. To position oneself in guard, therefore, many things must be observed, as seen in my figures: Standing firm over the feet, which are the base and foundation of the entire body, in a just pace, restrained rather than long in order to be able to extend, holding the sword and dagger strongly in the hands, the dagger now high, now low, now extended, the sword now high, now low, now on the right side, in place in order to parry and wound so that the enemy, throwing either a thrust or cut, can be parried and wounded in the same ''tempo'', with the ''vita'' disposed and ready because lacking its disposition and readiness it will be an easy thing for the enemy to put it into disorder with a ''dritto'', a ''riverso'', a thrust, or in some other manner, and even if such a person were to parry, they would remain in danger. It is advised that the dagger should guard the enemy’s sword because if the enemy throws, it will parry that, and that the sword should always aim at the uncovered part of the enemy so that he is wounded when throwing. This is all the artifice of this profession. Moreover, it must be noted that all motions of the sword are guards to those who know them, and all guards are good for the practised person, as, on the contrary, no motion is a guard to those who do not understand any, and they are not good for those who do not know how to use them.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|22|lbl=02|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|1|lbl=03|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|22|lbl=02|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|1|lbl=03|p=1}} | ||

| Line 373: | Line 373: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[3] As for counterguards, it is advised that someone who has knowledge of this profession will never position himself in guard but will seek to position himself in a counterguard. Wanting to do so, know this: One must position oneself outside of measure—that is, at a distance—with the sword and dagger high, strong with the vita, with a firm and stable pace, then consider the guard of the enemy. Afterwards, approach him little by little, binding with the sword to be safe—that is, almost resting your sword on his so that it covers it—because he will not be able to wound if he does not disengage the sword. The reason for this is that in disengaging he performs two actions: First, he disengages, which is the first ''tempo'', then wounding, which is the second. While he disengages, he can come to be wounded in many ways in the same ''tempo'' before he has time to wound, as will be seen in the figures of my book. If he changes guard due to the counterguard, it is necessary to follow him with the sword forward, with the dagger alongside always securing his sword, because in the first ''tempo'' he will always have to disengage the sword and necessarily ends up wounded. Neither will it ever be possible for him to wound if not with two tempi, and from those parrying will always be a very easy thing. This is enough about guards and counterguards.</p> | + | | <p>[3] As for counterguards, it is advised that someone who has knowledge of this profession will never position himself in guard but will seek to position himself in a counterguard. Wanting to do so, know this: One must position oneself outside of measure—that is, at a distance—with the sword and dagger high, strong with the ''vita'', with a firm and stable pace, then consider the guard of the enemy. Afterwards, approach him little by little, binding with the sword to be safe—that is, almost resting your sword on his so that it covers it—because he will not be able to wound if he does not disengage the sword. The reason for this is that in disengaging he performs two actions: First, he disengages, which is the first ''tempo'', then wounding, which is the second. While he disengages, he can come to be wounded in many ways in the same ''tempo'' before he has time to wound, as will be seen in the figures of my book. If he changes guard due to the counterguard, it is necessary to follow him with the sword forward, with the dagger alongside always securing his sword, because in the first ''tempo'' he will always have to disengage the sword and necessarily ends up wounded. Neither will it ever be possible for him to wound if not with two ''tempi'', and from those parrying will always be a very easy thing. This is enough about guards and counterguards.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 415: | Line 415: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[8] If he disengages, in the disengagement he can be wounded, and this is a ''tempo''. If he changes guard, while he changes is a ''tempo''. If he turns, it is a ''tempo''. If he binds to come to measure, while he walks before he arrives at measure is a ''tempo'' to wound him. If he throws, parrying and wounding in one ''tempo'' is also a ''tempo''. If the enemy stands still in guard in order to wait and you advance to bind him and throw where he is uncovered when you are at measure, it is a ''tempo''. This is because in every motion of the dagger, sword, foot, and vita, such as changing guard, is a ''tempo'' in the way that all these things are | + | | <p>[8] If he disengages, in the disengagement he can be wounded, and this is a ''tempo''. If he changes guard, while he changes is a ''tempo''. If he turns, it is a ''tempo''. If he binds to come to measure, while he walks before he arrives at measure is a ''tempo'' to wound him. If he throws, parrying and wounding in one ''tempo'' is also a ''tempo''. If the enemy stands still in guard in order to wait and you advance to bind him and throw where he is uncovered when you are at measure, it is a ''tempo''. This is because in every motion of the dagger, sword, foot, and ''vita'', such as changing guard, is a ''tempo'' in the way that all these things are ''tempi''—because they contain different intervals. While the enemy makes one of these motions, he will certainly be wounded because while one moves one cannot wound. It is necessary to learn this in order to be able to wound and parry. I will be demonstrating more clearly how one must do so in my figures.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/25|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/25|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/13|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/13|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 422: | Line 422: | ||

|- | |- | ||

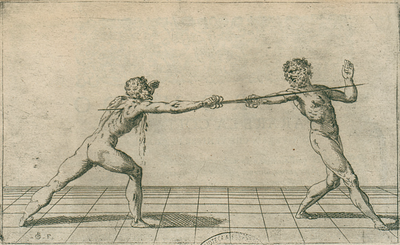

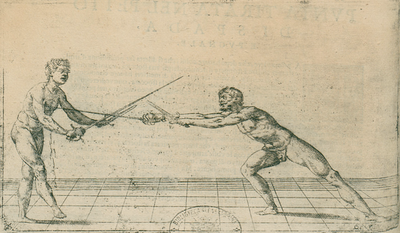

| [[File:Giganti 01.png|400x400px|center|Figure 1]] | | [[File:Giganti 01.png|400x400px|center|Figure 1]] | ||

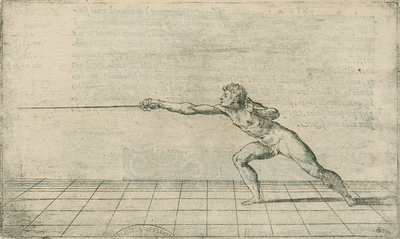

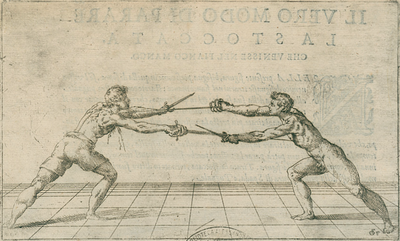

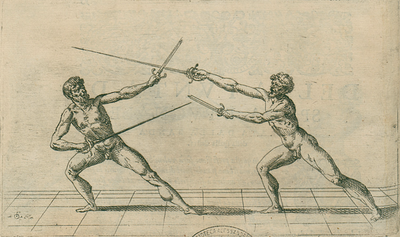

| − | | <p>[9] | + | | <p>[9] ''The method of throwing the ''stoccata</p> |

| − | <p>Now that we have discussed | + | <p>Now that we have discussed guards, counterguards, measures, and ''tempi'', it is necessary to demonstrate and make understood how one must carry the ''vita'' in order to throw a ''stoccata'' and escape, since, wishing to learn this art, it is first necessary to know how to carry the ''vita'' and throw long ''stoccate'', as seen in this figure. All lies in throwing long, brief, strong, and immediate ''stoccate'', withdrawing backward outside of measure. To throw the long ''stoccata'', one must position oneself in a just and strong pace, short rather than long in order to be able to extend and, in throwing the ''stoccata'', stretch the sword arm, bending the knee as much as possible. The proper method of throwing the ''stoccata'' is, after being positioned in guard, it is necessary to throw the arm first, then extend forward with the ''vita'' in one ''tempo'' so that the ''stoccata'' arrives and the enemy does not perceive it. If the ''vita'' were brought forward first, the enemy could notice it and, availing himself of the ''tempo'', be able to parry and wound in one ''tempo''.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|1|lbl=07}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|1|lbl=07}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/14|1|lbl=05}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/14|1|lbl=05}} | ||

| Line 431: | Line 431: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[10] In withdrawing backward one must first | + | | <p>[10] In withdrawing backward, one must first bring back the head, since behind the head will follow the ''vita'', and afterwards the foot. Bringing the foot back first and leaving the head and ''vita'' forward keeps them in great danger.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/14|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/14|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 438: | Line 438: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[11] Therefore, to learn this art well one must first practise throwing this stoccata. Knowing | + | | <p>[11] Therefore, to learn this art well, one must first practise throwing this ''stoccata''. Knowing this, the rest will be learned easily, and not knowing it, the contrary. Be advised, Lord Readers, that in my lessons I will place this method of throwing the ''stoccata'' many times where appropriate. This I know makes the lessons better understood. It is not said of me that I say one thing many times.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 447: | Line 447: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[12] | + | | <p>[12] ''Why begin with the single sword''</p> |

| − | <p>In my first book of arms I | + | <p>In this, my first book of arms, I intended to discuss only two kinds of weapons—that is, the single sword and the sword and dagger— setting aside discussion of some others. If it pleases the Lord, I will publish on all sorts of weapons as soon as possible. Because the sword is the most common and frequently used weapon of all, I wanted to begin with it, since one who understands playing with the sword well will also know a little of how to handle every other kind of weapon. Since it is not customary in every part of the world to carry the dagger, targa, or rotella, and as fighting with the single sword often occurs, I urge everyone to learn to play with the single sword first, in spite of everything that one might have in frays, such as the dagger, targa, or rotella, since occurring, as it many times does, that the dagger, targa, or rotella falls from his hand, it would be possible for a man to defend himself and wound the enemy with the single sword, and because one who is practised in playing with the single sword will know how to parry and wound just as well as if he had sword and dagger.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|4|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|4|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/16|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/16|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 456: | Line 456: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 02.png|400x400px|center|Figure 2]] | | [[File:Giganti 02.png|400x400px|center|Figure 2]] | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

[[File:Giganti 03.png|400x400px|center|Figure 3]] | [[File:Giganti 03.png|400x400px|center|Figure 3]] | ||

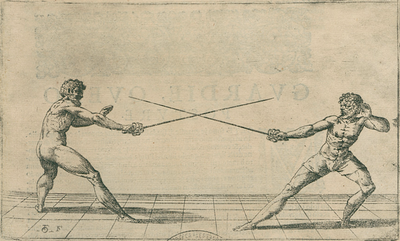

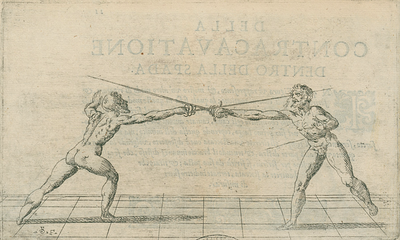

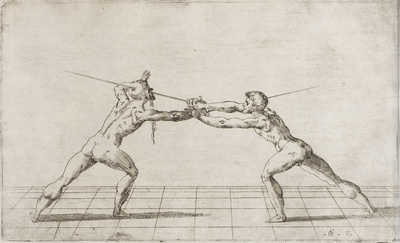

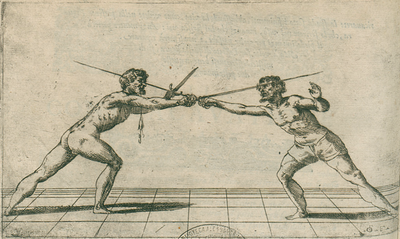

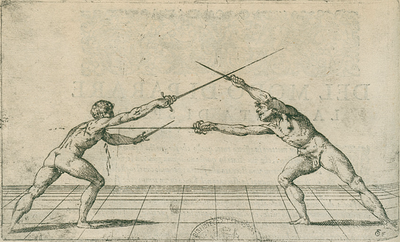

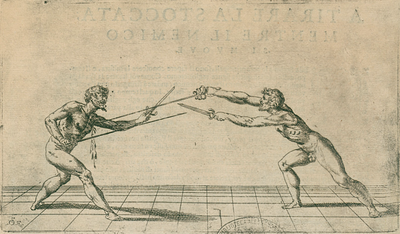

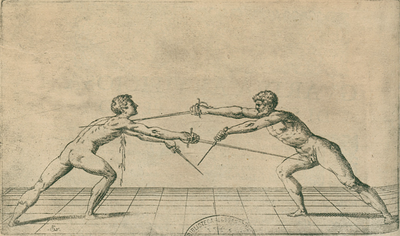

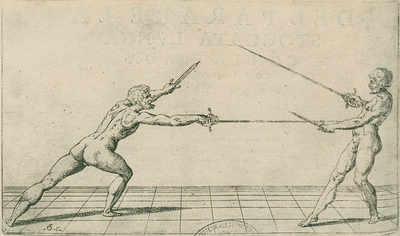

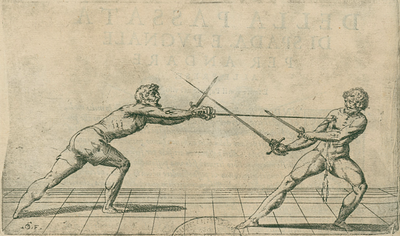

| <p>[13] '''Guards, or Postures'''</p> | | <p>[13] '''Guards, or Postures'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>Many are the guards of the single sword, and many still the counterguards. In my first book I will | + | <p>Many are the guards of the single sword, and many still the counterguards. In my first book I will teach no more than two sorts of guards and counterguards, which you will be able to avail yourself of for all lessons of the figures of this book. Therefore, before coming to do what you desire, you must go to bind the enemy outside of measure, securing yourself from his sword by placing your sword over his in a way that he cannot wound you if not with two ''tempi'': One will be the disengage of the sword, the other wounding you. You will arrange yourself in this way against all the guards, either high or low, according to how you see your enemy arranged, always taking care not to give him ease and opportunity to wound you in a single ''tempo''. You will do this if you take care that the point of his sword is not toward the middle of your ''vita'' so that, pushing his sword forward quickly and strongly, he cannot wound you. Therefore, cover the enemy’s sword with yours as you see in this figure so that the enemy’s sword is outside of your ''vita'' and he cannot wound you if he does not disengage his sword. Arrange yourself with your feet strong, stable with your ''vita'', with your sword arm extended and strong in order to parry and wound, as the figure shows you. If you were to see the enemy in a high or low guard and did not position yourself in a counterguard and secure yourself from his sword, you would be in danger even if your enemy had lesser science and lacked practice compared to you, since you could produce an ''incontro'' and both wound each other, or he could put you on the defensive, or rather, in obedience, with feints or disengages of the sword or other things that are possible. If you secure yourself from the enemy’s sword as I said above, he will not be able to move or perform any action that you will not perceive and be able to defend from with ease.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|30|lbl=10|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/31|1|lbl=11|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|30|lbl=10|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/31|1|lbl=11|p=1}} | ||

| Line 470: | Line 471: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[14] These figures here are two guards with the swords forward | + | | <p>[14] These figures here are two guards with the swords forward and two counterguards covering the sword. One is made going to bind the enemy on the inside and the other going outside, as these figures show you and as I will go about showing you in the subsequent lessons.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/31|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/31|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/20|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/20|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 477: | Line 478: | ||

|- | |- | ||

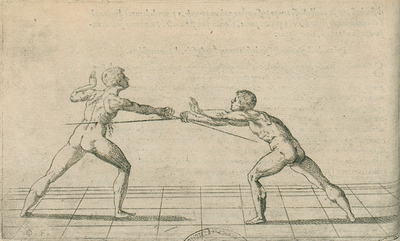

| rowspan="2" | [[File:Giganti 04.png|400x400px|center|Figure 4]] | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Giganti 04.png|400x400px|center|Figure 4]] | ||

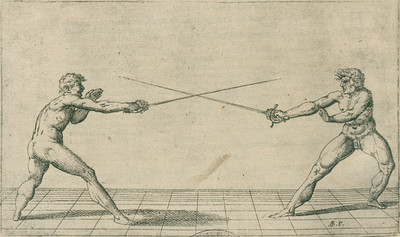

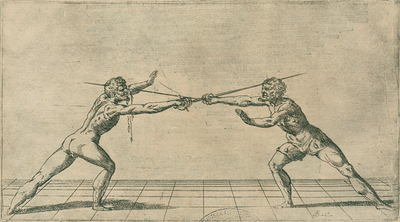

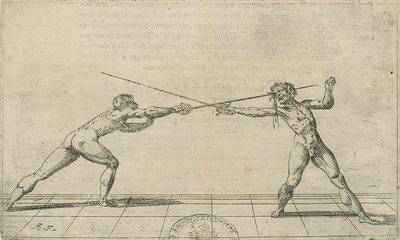

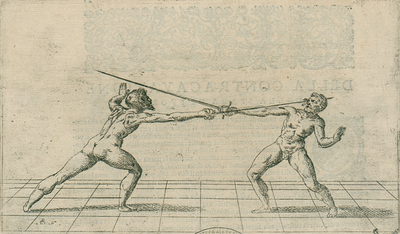

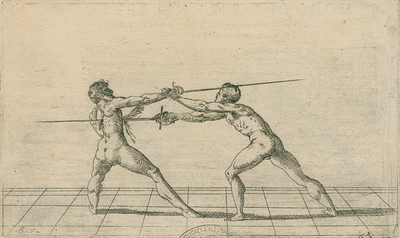

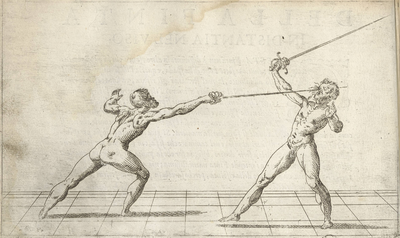

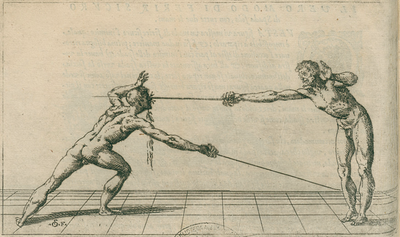

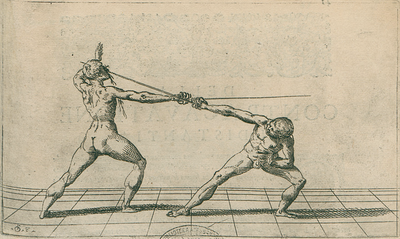

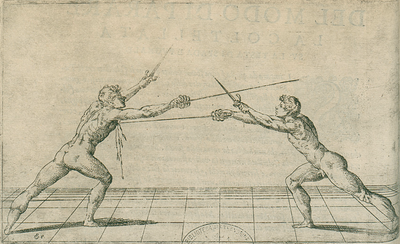

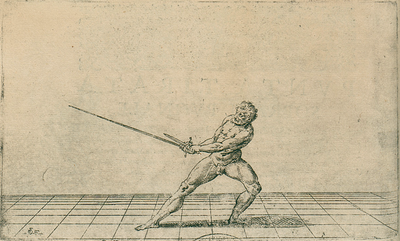

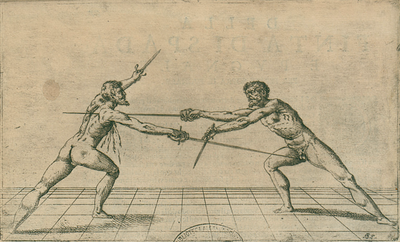

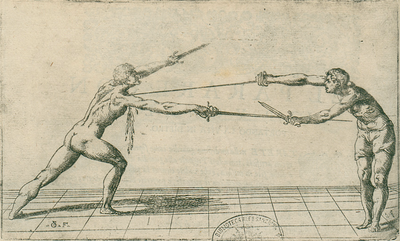

| − | | <p>[15] '''Explanation of Wounding in Tempo'''</p> | + | | <p>[15] '''Explanation of Wounding in ''Tempo'''''</p> |

| − | <p>This figure teaches you to wound your enemy in the tempo he disengages his sword. You do this by approaching to bind the enemy outside of measure, placing your sword over his to the inside as the figure of the first guard shows you<ref>Although the plates depicting the guards and counterguards are somewhat less than clear, we know from this chapter that Figure 2 depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the inside.</ref> so that he will not be able to wound you if he does not disengage the sword. Then, in the same tempo that he disengages to wound you, push forward your sword, turning your wrist in the same tempo so that you wound him in the face as | + | <p>This figure teaches you how to wound your enemy in the ''tempo'' that he disengages his sword. You will do this by approaching to bind the enemy outside of measure, placing your sword over his to the inside as the figure of the first guard shows you<ref>Although the plates depicting the guards and counterguards are somewhat less than clear, we know from this chapter that Figure 2 depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the inside.</ref> so that he will not be able to wound you if he does not disengage the sword. Then, in the same ''tempo'' that he disengages to wound you, push forward your sword, turning your wrist in the same ''tempo'', so that you wound him in the face as seen in the figure. In the case that you were to attempt to parry and then wound, it would not be successful, since the enemy would have time to parry and you would be in danger, but if you enter immediately forward with your sword in the ''tempo'' that he disengages his, turning your wrist and parrying, the enemy will have difficulty defending himself.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/33|1|lbl=13}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/33|1|lbl=13}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/21|1|lbl=09}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/21|1|lbl=09}} | ||

| Line 492: | Line 493: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[17] In the case that the enemy does not disengage his sword to wound you, I want you to advance to bind him inside of measure and immediately throw | + | | <p>[17] In the case that the enemy does not disengage his sword in order to wound you, I want you to advance to bind him inside of measure and immediately throw a thrust at him where he is uncovered, returning backward outside of measure and resting your sword over his.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/33|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/33|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/21|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/21|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 501: | Line 502: | ||

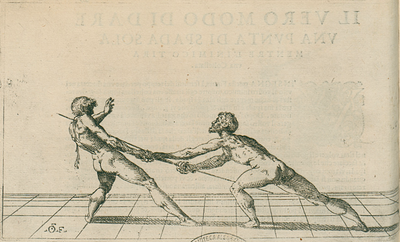

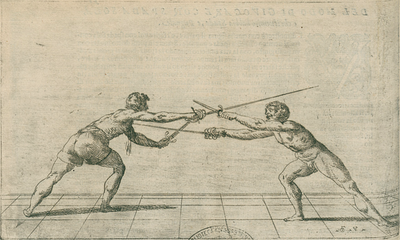

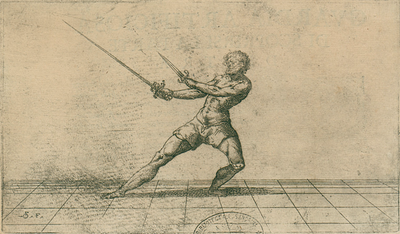

| <p>[18] '''The Proper Method of Going to Bind''' the Enemy and Strike Him while he disengages the sword</p> | | <p>[18] '''The Proper Method of Going to Bind''' the Enemy and Strike Him while he disengages the sword</p> | ||

| − | <p>From this figure you learn that if your enemy is in a guard with the sword on the left side, high or low, you approach him to bind him outside of his sword outside of measure, with your sword over his so that it barely touches it, with a just and strong pace, with your sword ready to parry and wound, with an alert eye, as you see in the second figure of the guards and counterguards.<ref>Figure 3, which we know from the description of this chapter’s action depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the outside.</ref> You being | + | <p>From this figure you learn that if your enemy is in a guard with the sword on the left side, high or low, you approach him to bind him on the outside of his sword from outside of measure, with your sword over his so that it barely touches it, with a just and strong pace, with your sword ready to parry and wound, and with an alert eye, as you see in the second figure of the guards and counterguards.<ref>Figure 3, which we know from the description of this chapter’s action depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the outside.</ref> You being arranged in this way, your enemy will not be able to wound you with a thrust if he does not disengage the sword. While he disengages, turn your wrist and in the same ''tempo'' throw a ''stoccata'' at him as the fourth figure teaches you. Having thrown this ''stoccata'', in the same ''tempo'' immediately return backward outside of measure, resting your sword over his so that if he were to attempt to disengage anew, you will throw the same ''stoccata'' at him again, turning your wrist as above and returning outside of measure. As many times as he disengages, that many times you will use the same method of turning your wrist and throwing the ''stoccata'' at him.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/35|1|lbl=15}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/35|1|lbl=15}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/23|1|lbl=10}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/23|1|lbl=10}} | ||

| Line 508: | Line 509: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[19] | + | | <p>[19] Much practice is required to perform this play well, since from this one learns to parry and wound with great skill and speed. Take care to always be balanced with your ''vita'' and to parry strongly with the ''forte'' of your sword because, if your enemy throws strongly at you, parrying strongly will make him disconcerted and you will be able to wound him where he is uncovered. This must be the first lesson that one learns with the single sword, since all the others that I have placed in this book arise from it. Knowing how to do this in ''tempo'' teaches you to parry all the cuts and resolute thrusts that can come for the head, which I will teach hand in hand in the subsequent lessons.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/35|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/36|1|lbl=16|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/35|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/36|1|lbl=16|p=1}} | ||

| Line 520: | Line 521: | ||

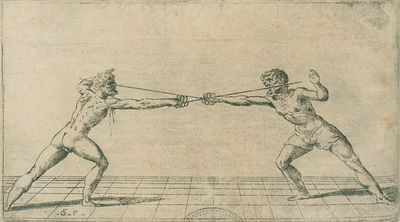

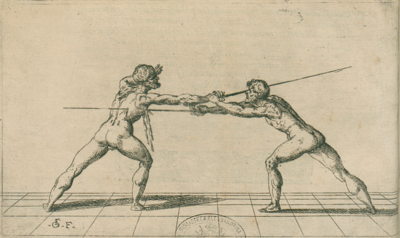

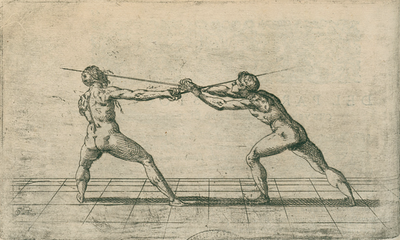

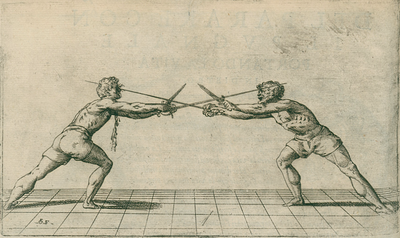

| <p>[20] '''The Proper Method of Disengaging the Sword'''</p> | | <p>[20] '''The Proper Method of Disengaging the Sword'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>The two figures | + | <p>The two figures placed above taught to wound the enemy while he disengages his sword. Because I would not leave a thing in my lessons that is not more than clear, I want to show you the method of disengaging the sword. Note, however, that your enemy being positioned in whichever sort of guard he wants, you having gone to bind him, throw a ''stoccata'' at him where he is uncovered and, if he knows as much as you, your swords will always be equal. I want you then to disengage the sword under the hilt of that of the enemy, quickly turning your wrist and throwing a thrust where you find him uncovered in the same ''tempo''. This is the proper and safe method to disengage the sword and wound in one ''tempo''. If you were to disengage your sword without turning your wrist, you would give the enemy a ''tempo'' and place to wound you, as you will see quite well in practising and trying it yourself. If the enemy were to parry, disengage again in the aforesaid way, always turning your wrist. As many times as he parries, disengage just as many other times in the above way, which is safest, then throw the ''stoccata'' at him in the ''tempo'' that you disengage. This method of disengaging is no less necessary than what was taught in the explanation of the previous figure on the method of parrying, since this is the main thing required in handling the single sword. Therefore, I exhort everyone to practise these two things well since, being at measure against the enemy, as soon as it is the ''tempo'' to disengage the sword, one should know how to disengage quickly and well, and as soon as it is the ''tempo'' of parrying, know how to parry similarly well.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/36|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|37|lbl=17|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/36|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|37|lbl=17|p=1}} | ||

| Line 530: | Line 531: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 06.png|400x400px|center|Figure 6]] | | [[File:Giganti 06.png|400x400px|center|Figure 6]] | ||

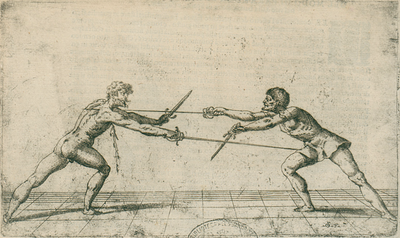

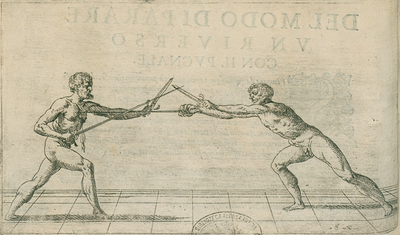

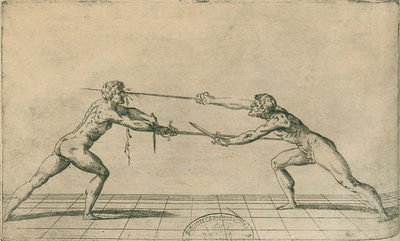

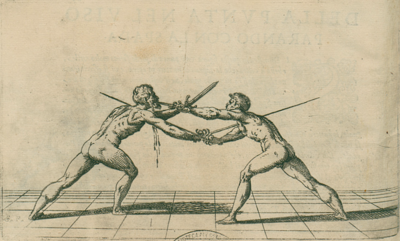

| − | | <p>[21] '''The Inside | + | | <p>[21] '''The Counterdisengage Inside of the Sword'''</p> |

| − | <p>In this figure<ref>Reading the text, Figures 6 and 7 appear to be swapped, meaning this lesson’s text refers to Figure 7. Interestingly the plate order does not appear to be corrected in subsequent printings, even in Jakob de Zeter’s German/French version (1619), which uses entirely new plates created by a different artist.</ref> another method of parrying and | + | <p>In this figure,<ref>Reading the text, Figures 6 and 7 appear to be swapped, meaning this lesson’s text refers to Figure 7. Interestingly, the plate order does not appear to be corrected in subsequent printings, even in Jakob de Zeter’s German/French version (1619), which uses entirely new plates created by a different artist.</ref> I depict and show you another method of parrying and wounding—by way of counterdisengage. It is done in this way: Having covered your enemy’s sword so that if he wishes to wound you, he must disengage, while he disengages, I want you also to disengage so that your sword returns to its first position, covering that of the enemy. But, in disengaging, availing yourself of the ''tempo'', throw a ''stoccata'' at him where he is uncovered, turning your ''vita'' a little toward the right side and holding your arm stretched forward so that if he comes to wound you, he will wound himself of his own accord. Having thrown the ''stoccata'', return backward outside of measure.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|39|lbl=19}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|39|lbl=19}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/26|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/26|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 541: | Line 542: | ||

| <p>[22] '''The Counterdisengage of the Sword on the Outside'''</p> | | <p>[22] '''The Counterdisengage of the Sword on the Outside'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>This method of wounding<ref>This lesson’s text refers to Figure 6.</ref> by | + | <p>This method of wounding<ref>This lesson’s text refers to Figure 6.</ref> by means of an outside counterdisengage is similar to the inside counterdisengage, only there is a difference: Your enemy being in guard and you coming to bind, being outside of measure, you must position yourself in a counterguard, securing yourself from his sword on the outside and making the enemy resolve himself to disengage. While he disengages, you disengage again in the same ''tempo'', turning the point of your sword under his along with your wrist, resting the ''forte'' of the edge of your sword and going along its edge, holding your arm long and extended, loosening the ''vita'' and lengthening the pace, as seen in the figure, so that you come to wound him without him perceiving it.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/41|1|lbl=21}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/41|1|lbl=21}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/28|1|lbl=13}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/28|1|lbl=13}} | ||

| Line 548: | Line 549: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[23] | + | | <p>[23] Be advised, though, that if the enemy throws the sword strongly, wishing to disengage yours so that the enemy does not reach and wound you, you must hold your ''vita'' back in your disengage so that you stay safe. Supposing the enemy had thrown strongly, he would disconcert himself and come to be wounded on your sword and you will stay superior to him, being able to wound him where you see fit, taking care to always hold your sword outside of your ''vita'' so that he cannot wound you.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/41|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/41|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/28|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/28|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 557: | Line 558: | ||

| <p>[24] '''Explanation of the Feint,''' ''Making a show of disengaging the sword with your wrist''</p> | | <p>[24] '''Explanation of the Feint,''' ''Making a show of disengaging the sword with your wrist''</p> | ||

| − | <p>The ways of wounding are various and consequently my lessons are also various. | + | <p>The ways of wounding are various and, consequently, my lessons are also various. Do not at all expect me to recount all things that are possible in this profession, however. Those being infinite, my work would be too long and bring tedium to its Readers. However, I will untangle those things that to me appear most beautiful, artificial, and useful, from which arise many others easier and less artificial.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/43|1|lbl=23}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/43|1|lbl=23}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/30|1|lbl=14}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/30|1|lbl=14}} | ||

| Line 564: | Line 565: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[25] Therefore, among all the methods of wounding | + | | <p>[25] Therefore, among all the methods of wounding with artifice, in my opinion the feint exceeds all others. This is nothing more than hinting at doing one thing and doing another. It is done in different ways, and they are these: I want you to position yourself standing on the right side, with the sword forward and your right arm extended in order to give your enemy occasion to come bind you. As he comes to measure with you, observe whether he wants to wound you from a firm foot or instead with a pass. You will recognize this at the disengage you perform with the sword. Disengage the sword with your wrist and feign throwing a thrust at his face but throw wide of the enemy’s sword so that it does not find yours. If the enemy does not parry, throw it resolutely so that you wound him. If he parries, in his parrying redisengage the sword and wound as you see in this figure, where the enemy carelessly wounds himself. In redisengaging, take care that you do not let the sword be found because then your plan would fail, and, in disengaging, bring the head and ''vita'' back a little in order to see what the enemy does because if he were to throw and you had not pulled back, he could produce an ''incontro'' and you would wound each other. Moreover, you must be advised to run with the right edge of your sword along the edge of the enemy’s sword, turning the inside of your wrist upwards in wounding with your sword over the ''debole'' of that of the enemy. As soon as the ''stoccata'' is given, either resolute or feinted, return backward outside of measure, securing yourself as I showed you above.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/43|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|1|lbl=24|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/43|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|1|lbl=24|p=1}} | ||

| Line 574: | Line 575: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[26] The feint is therefore performed in this way: | + | | <p>[26] The feint is therefore performed in this way: First the sword is presented to either the face or chest of the enemy, then the arm is extended without stepping. Whence, if the enemy attempts to parry, you disengage the sword in the same ''tempo'', accompanying it forward with the step so that you wound him unawares.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 581: | Line 582: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[27] If he does not parry, | + | | <p>[27] If he does not attempt to parry, extend the pace and strike him. This is the method of wounding by feint.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 588: | Line 589: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[28] | + | | <p>[28] Even though they appear similar, the following two figures are nevertheless different from each other because they contain different methods of feinting. Although they contain almost the same end to their wounding, and it would have sufficed to place a single figure with which to discuss and teach different methods of feinting in order to wound, in order to show clearly the different ways of feinting I wanted to put two of them here that differ widely from each other, which I show you in their explanations.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|45|lbl=25}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|45|lbl=25}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|4|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|4|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 595: | Line 596: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 09.png|400x400px|center|Figure 9]] | | [[File:Giganti 09.png|400x400px|center|Figure 9]] | ||

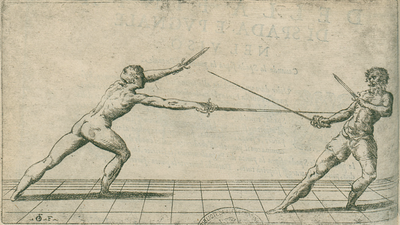

| − | | <p>[29] '''Method of Wounding | + | | <p>[29] '''Method of Wounding the Chest with the Single Sword When They<ref>The two fencers.</ref> Are At''' measure with the swords equal</p> |

| − | <p>The present figure is an artificial way of wounding the enemy in the chest and securing oneself from his sword so that he cannot offend while you pass to wound him. It is done in this way: | + | <p>The present figure is an artificial way of wounding the enemy in the chest and securing oneself from his sword so that he cannot offend while you pass to wound him. It is done in this way: It is necessary to place oneself in guard with the sword forward on the left side and, if the enemy comes to bind you and cover your sword with his, let him come until he is at measure with you. Disengage when he is at measure with you, putting your sword inside of his and directing the point toward the enemy’s face. If he does not attempt to parry, wound him resolutely, running with the right edge of your sword on the edge of his as I said above, turning your wrist and bringing your body across somewhat. If the enemy comes to parry and wound you while you disengage, however, do not throw the thrust but hold it a little outside, and in the same ''tempo'' that he wants to parry and wound, redisengage your sword under the hilt of his, aiming at the enemy’s chest so that you strike him there safely, extending a little with the sword as you see in the present figure,</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/47|1|lbl=27}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/47|1|lbl=27}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/33|1|lbl=16}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/33|1|lbl=16}} | ||

| Line 604: | Line 605: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[30] taking care to disengage and redisengage it in the same tempo, never holding it still so that the enemy does not find it. In the movement he makes to parry, pass to him with your vita on the outside, taking care to place your hand on the hilt of | + | | <p>[30] taking care to disengage and redisengage it in the same ''tempo'', never holding it still so that the enemy does not find it. In the movement he makes in order to parry, pass to him with your ''vita'' on the outside, taking care to place your hand on the hilt of his sword. This pass produces this effect: It removes his ability to wound you and you can wound him how and where you wish and please.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/47|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/47|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/33|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/33|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 611: | Line 612: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 10.png|400x400px|center|Figure 10]] | | [[File:Giganti 10.png|400x400px|center|Figure 10]] | ||

| − | | <p>[31] '''The Pass | + | | <p>[31] '''''The Pass by Means of Feint at a Distance'''''</p> |

| − | <p>This is | + | <p>This is a way of passing at the enemy with artifice so that he does not perceive it, and it is highly regarded for the effect it illustrates, as seen in the present figure where one passes with a feint and proceeds to wound the enemy. It is done in this way: It is necessary to see in which guard your enemy positions himself and how he is arranged and go to bind him in guard, directing the point of your sword at his face. If you see that he stays waiting and doesn’t move when you find yourself almost at measure, strongly throw a thrust at his face as figure number [7]<ref>The placeholder was never replaced with the proper figure number reference when the book went to print, and it remains missing in Paolo Frambotto’s 1628 reprint. Jakob de Zeter’s 1619 German/French version refers to Figure 7. </ref> shows. If he does not parry strongly, you produce the effect of figure number [8]</ref>The figure number is missing in both the 1606 and 1628 printings. Jakob de Zeter’s 1619 German/French version refers to Figure 8.</ref> and have no need to perform other feints, but if he parries, you will both be with your swords equal. Immediately return backward outside of measure and put yourself in the same guard as at first and, when you are almost at measure, feign throwing the same thrust at his face. While he attempts to parry it, disengage the point of your sword under the hilt of the enemy’s with your wrist, being sure to keep the enemy’s sword outside of your ''vita''. Then, in the same ''tempo'', pass, running with your sword over the hilt of his, accompanying it with the left hand and immediately putting it over the hilt of the enemy sword so that he cannot give you a riverso in the face, so that without doubt you will wound him, since he does not see your goal. This done, leap out of measure and replace the sword within that of the enemy, securing yourself in the above way and, beating his sword, you will wound him again with two or three resolute and irreparable thrusts.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/49|1|lbl=29}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/49|1|lbl=29}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/35|1|lbl=17|p=1}} {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/37|1|lbl=18|p=1}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/35|1|lbl=17|p=1}} {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/37|1|lbl=18|p=1}} | ||

| Line 620: | Line 621: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[32] | + | | <p>[32] ''The pass by means of feint over the point of the sword''</p> |

| − | <p>This is another kind of disengage and feint | + | <p>This is another, not commonly used, kind of disengage and feint which produces the effect of the previous two figures. It is done so: One must put oneself in guard with the sword to the left side, with the arm extended and long. Letting the enemy come to bind you in the described way, disengage your sword over the point of his when he is at measure. If you see that he does not parry, throw at him strongly and resolutely, as I have said to you, which will not require other feints. If he parries, though, do not stop the sword but avoid the guard of his sword, pass in the above way, and wound him in the chest, withdrawing afterwards as said.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/49|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/49|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/37|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/37|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 631: | Line 632: | ||

| <p>[33] '''The Feint to the Face at a Distance'''</p> | | <p>[33] '''The Feint to the Face at a Distance'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>This feint is | + | <p>This feint is different only in that the previous feint completes its disengage under the hilt of the sword and this does so over it in order to throw at the enemy’s face. This ''stoccata'' becomes a feint if he parries and is resolute if he does not. Then the same guards, distances, and measures are observed in the rest. One likewise carries the ''vita'' and sword as seen in the figure and immediately returns outside of measure as soon as the thrust is thrown. The most important thing is knowing how to make the feint natural so that it cannot be distinguished from resolute, which is done in this way: The point is turned (for example) upward on the outside at his face and, in advancing with the point underneath the hilt of the enemy sword to wound him inside, it is necessary that the thrust wounds his face or chest with the disengage. This is what is meant by “natural feint”. However, you are advised never to perform a feint if the enemy does not parry resolutely, because you would be in danger of both wounding each other and end up in danger.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|51|lbl=31}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|51|lbl=31}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/38|1|lbl=19}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/38|1|lbl=19}} | ||

| Line 640: | Line 641: | ||

| <p>[34] '''The Proper Method to Give a Thrust with the Single Sword while the Enemy Throws''' a cut</p> | | <p>[34] '''The Proper Method to Give a Thrust with the Single Sword while the Enemy Throws''' a cut</p> | ||

| − | <p>This figure teaches you to avail yourself of the tempo in order to give your enemy a stoccata to the face while he raises | + | <p>This figure teaches you to avail yourself of the ''tempo'' in order to give your enemy a ''stoccata'' to the face while he throws a cut at your head—when he raises his sword, he can be given a ''stoccata'' while it is in the air and before it reaches you. Note how this is done. After having positioned yourself in whichever guard you like, go to bind your enemy. When you are at measure, if the enemy throws a cut toward your head, make use of the ''tempo'' in the raising of his sword, enter forward, and push the sword at his face so that you will without doubt wound him while his sword is in the air, as you see in the figure. But, in throwing, turn your wrist and the right edge of the sword upwards, holding your arm long and high, and make the guard of your sword cover your head so that if the enemy drops his sword, you are covered and he cannot offend you.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/53|1|lbl=33}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/53|1|lbl=33}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/40|1|lbl=20}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/40|1|lbl=20}} | ||

| Line 647: | Line 648: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[35] It is necessary, however, to throw this thrust quickly. | + | | <p>[35] It is necessary, however, to throw this thrust quickly. If it were not performed quickly, the enemy would parry it and wound you. After you have thrown, quickly withdraw backward outside of measure, securing yourself with your sword against that of the enemy.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/53|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/53|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/40|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/40|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 654: | Line 655: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[36] I did not want to put all the | + | | <p>[36] I did not want to put all the methods of parrying cuts, which are many, in my first book. Rather, I have placed this alone for you, it appearing to me most useful and commodious for learning how to recognize the ''tempo'' and make use of it—something necessary to understand at all times.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/53|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/53|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/40|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/40|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 661: | Line 662: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 13.png|400x400px|center|Figure 13]] | | [[File:Giganti 13.png|400x400px|center|Figure 13]] | ||

| − | | <p>[37] '''The Proper Way to Safely Wound''' with the single sword using both hands</p> | + | | <p>[37] '''''The Proper Way to Safely Wound''' with the single sword using both hands''</p> |

| − | <p>This figure shows you a method of safely wounding the enemy which is impossible to parry. It is done in two | + | <p>This figure shows you a method of safely wounding the enemy which is impossible to parry. It is done in two ways: First, it is necessary to find occasion to have your sword equal with the enemy’s, yours on the outside. You then shove your sword at the enemy’s face which, if not parried strongly, strikes him in the face as seen in the fourth figure. If he parries well and strongly, extend with your left foot, putting your left hand over your sword, pressing strongly with both hands, directing the point toward the enemy’s chest and lowering the hilt of your sword as seen in the present figure, taking care to do all these things in one ''tempo''.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/55|1|lbl=35}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/55|1|lbl=35}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/42|1|lbl=21}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/42|1|lbl=21}} | ||

| Line 670: | Line 671: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[38] Next,<ref>This is the second manner mentioned at the beginning of the lesson, rather than an action that follows from the first.</ref> | + | | <p>[38] Next,<ref>This is the second manner mentioned at the beginning of the lesson, rather than an action that follows from the first.</ref> arranged in guard in the aforesaid way but with your sword on the inside, I want you to disengage the sword as if to wound on the outside and, in the same ''tempo'' that you disengage the sword, place your left hand over your sword and beat the enemy sword with yours using the strength of both hands. That beaten away, immediately pass forward with your left foot as seen in the figure. For this to turn out well for you, be aware that it is necessary to do all these things in one ''tempo''—that is, disengaging the sword, placing your hand on it, beating the enemy’s sword with yours, and passing forward with the left foot. Not doing these things in one ''tempo'', you could fail and be in danger, as you would be with certain valiant men who know how to disengage the sword quickly and well. Therefore, to succeed at this, you must do it quickly and suddenly.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/55|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/55|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/42|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/42|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 677: | Line 678: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 14.png|400x400px|center|Figure 14]] | | [[File:Giganti 14.png|400x400px|center|Figure 14]] | ||

| − | | <p>[39] '''The Proper | + | | <p>[39] '''The Proper Method to Defend Against the Cut''' or ''Riverso'' that Comes at the Leg</p> |

| − | <p>In this lesson, | + | <p>In this lesson, wherein we will discuss the ''mandritto'' or riverso cut to the leg, it is not possible for me to say anything further to teach parrying and wounding the enemy in the same ''tempo''. Rather, I will say why the enemy ends up offending himself on the point of your sword. The enemy dropping a ''dritto'' or riverso at your leg, though, it is necessary that he lengthen his step and ''vita'' and bring his face forward. While the enemy drops to wound you, you then move your front leg, lifting it backward, and in the same ''tempo'' throw a thrust at his face so that he wounds himself of his own accord without the ability to parry, nor can he then wound you. Then (as I have said other times) return backward outside of measure.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/57|1|lbl=37}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/57|1|lbl=37}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/44|1|lbl=22}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/44|1|lbl=22}} | ||

| Line 686: | Line 687: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[40] And since the present lesson is very artificial it is necessary to learn it in order to be able to make use of it in such | + | | <p>[40] And, since the present lesson is very artificial, it is necessary to learn it in order to be able to make use of it in such an occasion as the figure clearly shows you.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/57|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/57|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/44|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/44|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 695: | Line 696: | ||

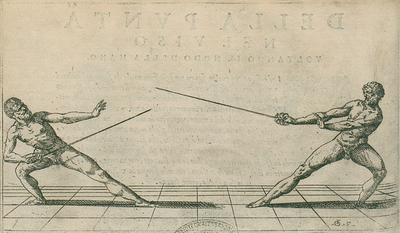

| <p>[41] '''The Inquartata''' or Slip of the Vita</p> | | <p>[41] '''The Inquartata''' or Slip of the Vita</p> | ||

| − | <p>Knowing the inquartata, or slip, is necessary | + | <p>Knowing the ''inquartata'', or slip, is necessary for mastering the body. However, this is not ordinarily used in schools, except by the French in order to exercise the ''vita''. Truthfully, many are these slips, or ''inquartate'', but I decided to show only three of them in this, my first book—in my view the safest and most beautiful, as revealed in the present figure.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/59|1|lbl=39}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/59|1|lbl=39}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/46|1|lbl=23}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/46|1|lbl=23}} | ||

| Line 701: | Line 702: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[42] The first of these is | + | | <p>[42] The first of these is performed by positioning yourself in guard outside of measure with the right foot forward, with the sword long and the arm extended, standing strongly on the right side, holding the point of the sword toward the enemy’s face. Let the enemy come to bind you and when he is almost at measure, disengage the sword a little wide as a feint. In the ''tempo'' the enemy attempts to parry, redisengage the sword, returning it to its first position, running along the edge of his sword with the disengage in a way that no sooner have you have disengaged than you have wounded the enemy, because if you attempt to disengage the sword and then wound, you would be in danger, since there would be two ''tempi''. Bring both the left leg and shoulder crosswise and, turning, produce the effect, giving him (as seen in the figure) a thrust in either the face or chest without him perceiving your goal, holding your arm stiff, with the hilt of your sword covering you, far from the sword of the enemy. Keep your eyes on his face, taking care not to turn your face with your ''vita'', as some do, <ref>[[Camillo Agrippa]] (1553), for example, recommends turning the face away.</ref> because you would find yourself in danger and not see your action. After this, immediately return backward out of measure with your sword over his, securing yourself as above.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/59|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/59|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/46|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/46|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 708: | Line 709: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[43] ''' | + | | <p>[43] ''The ''inquartata'', or slip of the vita''</p> |

| − | <p>This is no different from the | + | <p>This ''inquartata'' is no different from the first except in the way in which it wounds—that is, taking care in running along the edge of the enemy’s sword to go to wound him under the pommel of his sword, lifting the arm with the wrist, as seen in the figure, and after having turned your person, to stop yourself and not pass onto the enemy in order not to come to grips, because you would be in danger of being unable to return outside of measure and secure yourself from him. This ''inquartata'' is very difficult to parry. In fact, I will say it is impossible when it is done judiciously.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/59|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/59|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/48|1|lbl=24}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/48|1|lbl=24}} | ||

| Line 717: | Line 718: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[44] '''The Third Inquartata,''' or slip of the vita</p> | + | | <p>[44] '''''The Third ''Inquartata'',''' or slip of the vita''</p> |

| − | <p>This third inquartata is the most beautiful and | + | <p>This third ''inquartata'' is the most beautiful and safe of all. It is done in this way: Place yourself in guard as in the other two, holding the sword along the right side with your arm extended and firm. While the enemy comes to bind you with his sword over yours, disengage the sword with a turn of your wrist when you are at measure. If he does not parry, strike him in the face and produce the effect of the figure without needing to do more. If he parries, though, you find yourself with your swords equal. Strongly affront your sword onto his so that he also affronts and, disengaging as he does, run under the hilt of his sword with the disengage, turning your body as above, and wound him in the chest, which he will not perceive. The effect of the present figure produced, you will return outside of measure, securing yourself as in the other lessons.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/60|1|lbl=40}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/60|1|lbl=40}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/48|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/48|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 726: | Line 727: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[45] | + | | <p>[45] ''An artificial method to strike the chest, affronting the swords''</p> |

| − | <p>In the previous lessons I | + | <p>In the previous lessons I showed the method of the ''inquartate''—that is, how the swords are affronted on the outside in order to come to wound the enemy on the inside. Now I will briefly say how the swords are carried on the inside and wound on the outside. As you meet with the enemy, affront strongly with the edge of your sword, holding the point toward his face with your ''forte'' over the enemy’s sword. If he is weaker than you, give him a ''stoccata'' in either the face or chest that he cannot parry. If he is stronger than you, feeling how much your sword is affronted, disengage your sword under his hilt so that his falls downward and he similarly takes a thrust from which he cannot defend himself. In the same ''tempo'', pass without any danger and, placing your left hand on his hilt, wound him with three or four thrusts that cannot be avoided. Then, return outside of measure, securing yourself as above.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/60|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/61|1|lbl=41|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/60|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/61|1|lbl=41|p=1}} | ||

| Line 736: | Line 737: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[46] | + | | <p>[46] ''The method of playing single sword against single sword with resolute thrusts''</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>In schools, there are many who resolutely come throwing thrusts, imbroccate, and cuts when they assail the enemy, giving no ''tempo'' and always throwing with fury and very great impetus. These things ordinarily confound and disorder every beautiful player and fencer, for which reason it is necessary to know how to defend oneself in such an occasion.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/61|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/61|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 747: | Line 748: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[47] It is necessary that you place yourself | + | | <p>[47] It is necessary that you place yourself in guard against the enemy sword with yours ready to defend, outside of measure, in a pace that is restrained rather than long. In the ''tempo'' that he throws a thrust, ''imbroccata'', ''stoccata'', or other similar blow at you, beat his sword with the ''forte'' of yours and, immediately lengthening your step, throw him a thrust and wound him in the chest or face and quickly return backward with the lead foot to where you were before, resting your sword on his in order to secure yourself from it, in a way that he cannot wound if he does not disengage. If the enemy disengages, turning your wrist to the outside, beat his sword again with the ''forte'' of yours and, lengthening your pace, throw him a thrust and wound him, then quickly return backward with the foot as above, likewise securing yourself from his sword with yours. If he redisengages again, always repeat doing the same.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/61|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/61|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/50|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/50|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 754: | Line 755: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[48] This lesson is more useful than beautiful and contains two tempi which you can make before the enemy has time to make one of them | + | | <p>[48] This lesson is more useful than beautiful and contains two ''tempi'' which you can make before the enemy has time to make one of them: the first is the parry, the other the wound. Since they have been examined, you have understood.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/61|4|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/61|4|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/50|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/50|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 761: | Line 762: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 16.png|400x400px|center|Figure 16]] | | [[File:Giganti 16.png|400x400px|center|Figure 16]] | ||

| − | | <p>[49] '''Parrying Stoccate''' that Come at the Chest with the Single Sword</p> | + | | <p>[49] '''Parrying ''Stoccate''''' that Come at the Chest with the Single Sword</p> |

| − | <p>Seen in this figure is the safe method of parrying thrusts that come at your chest | + | <p>Seen in this figure is the safe method of parrying thrusts that come at your chest and then wounding the chest. It is done in different ways because some pass at a distance, others stand at measure, and others inside the measure, but someone who understands ''tempo'' and knows how to parry well, as my figure shows you, will defend against all these methods. Therefore, note that being with your enemy with your swords equal, if he passes in order to wound you in the chest, it is necessary to follow his sword with yours in the same ''tempo'', lowering, however, the point of yours by raising your wrist, parrying with the same and passing with your left foot toward his right side, taking yourself away from his sword. Wound him in the chest, holding your left hand over the hilt of his sword, and then, the ''stoccata'' given, disengage the sword in the way described above, returning backward outside of measure.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|63|lbl=43}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|63|lbl=43}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/51|1|lbl=27}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/51|1|lbl=27}} | ||

| Line 770: | Line 771: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 17.png|400x400px|center|Figure 17]] | | [[File:Giganti 17.png|400x400px|center|Figure 17]] | ||

| − | | <p>[50] '''The Thrust | + | | <p>[50] '''The Thrust to the Face''' Turning Your Wrist<br/><br/></p> |

| − | <p>With this figure you are taught a very beautiful method of wounding your enemy’s face | + | <p>With this figure you are taught a very beautiful method of wounding your enemy’s face. It consists entirely in seizing the occasion of being with the swords equal and causing your enemy to be in the motion of parrying by giving him the suspicion that you want to disengage the sword. In the same ''tempo'', turning your wrist, put your left hand on the guard of his sword and extend with the foot in one ''tempo'' so that you strike him in the face, as you see. Performing it properly, it cannot be parried. Having struck, extend with your left hand over the hilt of the enemy’s sword and, redisengaging the sword, you can give him two or three ''stoccate'' wherever you wish. Then, return backward outside of measure, always holding your sword over theirs, as above.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|65|lbl=45}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|65|lbl=45}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/53|1|lbl=28}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/53|1|lbl=28}} | ||

| Line 779: | Line 780: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 18.png|400x400px|center|Figure 18]] | | [[File:Giganti 18.png|400x400px|center|Figure 18]] | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

[[File:Giganti 19.png|400x400px|center|Figure 19]] | [[File:Giganti 19.png|400x400px|center|Figure 19]] | ||

| <p>[51] '''The Counterdisengage at a Distance'''</p> | | <p>[51] '''The Counterdisengage at a Distance'''</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>These<ref>The two preceding figures.</ref> are one and the same counterdisengage at a distance against someone who has their left foot forward and wishes to pass with an ''inquartata''. With these figures I wanted to show you the postures and the wound so that it can be thoroughly understood. It is necessary (when someone is coming to bind you with their left foot forward) that you stand in guard as you see in this figure, giving your enemy a chance to throw at your chest. If he is a valiant man, he will quickly pass with his foot and strongly turn his wrist in the manner of the ''inquartata'' in order to defend himself from your sword. In the same ''tempo'' that he passes, redisengage the sword under the hilt, lowering your ''vita'' as you see in the present figure so that you wound him in the face before he wounds you. In fact, he is unable to parry while he carries his foot forward to pass. In order to produce the effect of this figure on occasion, it is necessary to practise well the two figures placed above.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|68|lbl=48|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|69|lbl=49|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|68|lbl=48|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|69|lbl=49|p=1}} | ||

| Line 791: | Line 793: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 20.png|400x400px|center|Figure 20]] | | [[File:Giganti 20.png|400x400px|center|Figure 20]] | ||

| − | | <p>[52] '''Method of Playing with the Single Sword,''' while the enemy has sword and dagger</p> | + | | <p>[52] '''''The Method of Playing with the Single Sword,''' while the enemy has sword and dagger''</p> |