|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Pseudo-Ibn Akḥī Ḥizām

| Pseudo Ibn Akḥī Ḥizām | |

|---|---|

| Born | 10th AH/15th CE century Egypt? Syria? |

| Occupation | Mamluk scribe? |

| Nationality | Circassian Period (“Burjī”) Mamluk |

| Influences |

|

| Genres | Military manual |

| Language | Arabic, Egyptian Colloquial Arabic |

| Manuscript(s) | MS Arabe 2824 (1470) |

Kitāb al-makhzūn: Jāmiʿ al-funūn ("The Treasure: A Work that Gathers Together Combative Arts"; colophon dated 875 AH/1470-1CE) is an Arabic language work in the classical style of Mamluk furūsīya literature.[1] The work is attributed to the famous «father» of Islamicate martial arts literature Ibn Akhī Ḥizām (c. 250 AH/ 864 CE; given as Ibn Akhī Khuzām), yet is clearly the work of a Mamluk author.[2] Agnès Carayon suggests that a grandee of the Circassian Mamluk (Burjī) court commissioned the work, potentially for Sultan Qāʾitbay (r. 1468-1496).[3] Composite in nature, the work is most likely a summary of other, more voluminous works—such as Nihāyat al-suʾl wa-l-amnīya fī taʿlīm aʿmāl al-furūsīya ("The End of Questioning: A Trustworthy Work concerning Instruction in the Deeds of Furūsīya") by Al-Aqsarāʾī (c. 9th cent. AH/14th cent CE).[4] Certain sections begin and then trail off, while others remain incomplete, suggesting that this work is composite in nature and was most likely a summary or copy of other works both extant and lost. The author does not cite other authors within the body of the text itself.

The text of Jāmiʿ al-funūn is by and large more classical in nature with a great deal of dialectal, Egyptian Arabic of the period. This pertains both to vocabulary (ex: bāṭ for ibāṭ "armpit" throughout; jawwān as a preposition) as well as to grammar (verbs not in gender alignment, plurality disagreements, grammatical inconsistencies of adverbial phrases etc.). An introductory phrase in Ottoman Turkish in the beginning of the text has it that on «The seventh night of Muharram, 975 AH (1567CE)” a certain “Ṣilāhdār Aǧa” Dervish (unknown) petitioned God to be among those counted as Muhammad’s companions.[5] Likewise, the intricate title page has “The owner of this work is Derviş Ağa” crossed out in black ink.[6] Whether or not this was a higher ranking “Arms-Bearer” of the Sultan cannot be confirmed. The version from which the following translation stems is Bibliothèque Nationale MS 2824 (another version can be found in the same collection: MS 2826). Scholars have yet to produce a critical edition of this work.

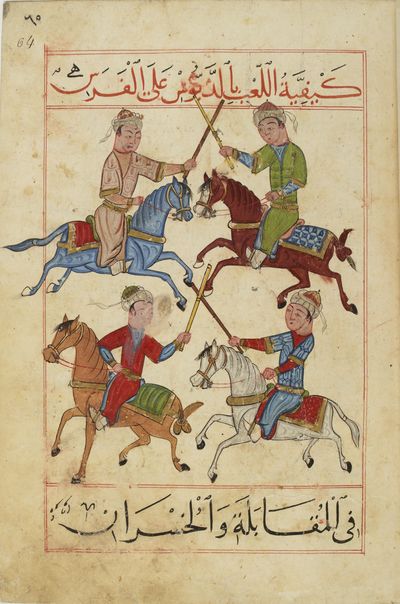

Despite its brevity in comparison to other works of the Mamluk furūsīya tradition, Jāmiʿ al-funūn provides a great deal of insight into the ways in which the Mamluks trained their troops. The illustrations featured in the work are some of the best examples of the medium.[7] Distinct from other works in the genre with lengthy introductions, Jāmiʿ al-funūn begins with only minor benedictions, then jumps straight into a description of how to establish the training area for cavalry exercises – the nāwārd. From there, the author displays 72 bunūd or paired lance exercises – most likely inspired by al-Ṭarāblūsī’s famous 72 forms (c . 738 AH / 1337-8 CE).[8] Following this, the author then treats issues deemed relevant to the development of a cavalier, without a particular logic to the ordering of the sections.

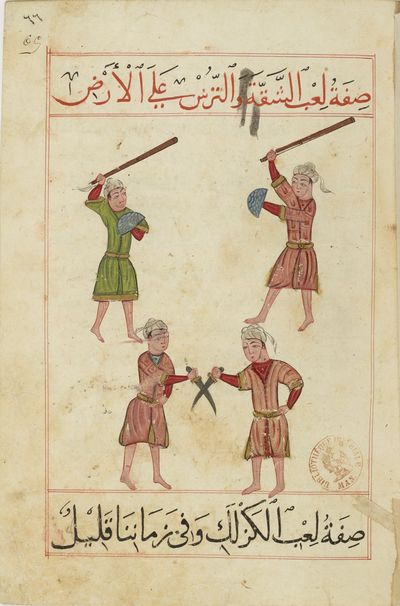

Unlike other works of furūsīya, Jāmiʿ al-funūn contains several sections detailing the ways in which soldiers can train for combat on foot. Most notably, the author presents a system for training swordsmanship. The work begins with instruction on the ways in which one can execute paired exercises with cane fighting, dagger fighting, and cane and shield fighting on foot. The author details the proper ways to feint and hit, the ways in which one can parry and riposte (and disarm), and where to target with a sword. In the author’s system, training with the cane was a safe means to perfect one’s technique before moving on to using sharp swords in battle. After training with the cane, the author recommends perfecting test cutting on clay mounds as a way to develop arm strength and ensure proper edge alignment. Following both of these methods of training, a potential cavalier would be ready to pursue test cutting on horseback.

Contents

Treatise

The translation of these two sections was prepared as part of The Mamlulk Project.

Illustrations |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

In the name of God, The Most Compassionate, The Most Merciful, with whom is my trust...[9] |

||

Chapter of Beginning to ride and learning Furusiya[10] All praise is to God, Owner of Greatness, The Most exalted by His Capabilities over His' resemblances and likenesses, The Owner of Glory, Honor, and Dominion. I praise Him more than others who praise Him, and may the Peace and Blessings of God be upon our Prophet Mohammed, the seal of the prophets and the messenger of the Lord of all Worlds, who was sent calling to God by His will and sent as a warner so that those who were to perish and those who were to survive might do so after the truth had been made clear to both. Surely God is All-Hearing, All-Knowing. Mohammed was sent after a period of suspension of messengers and a fading of knowledge, and God—Glorified and Exalted is He—spoke of fighting against those who oppose him and go astray in His book as He said: "O Prophet! Struggle against the disbelievers and the hypocrites and be harsh upon them." (9:73) And God—the Honoured and Glorified—said in what He sent down of the truth in which we believe: "fight them and God will punish them at your hands, put them to shame, help you overcome them, and soothe the hearts of the believers" (9:14) and said: "Fight against them if they persecute you until there is no more persecution, and your devotion will be to God alone." (2:193) and said: "O believers! Fight the disbelievers around you and let them find firmness in you. And know that God is with those mindful of Him." (9: 123) And we have seen nothing harder on them, nor firmer on them, nor fitter to their eyes, nor more harmful to them than fighting people of knowledge from among the fursan[11] whose riding is firm, stabbing is tight, archery is correct, bravery is acute, and fencing is sharp. |

||

And God is always—by His Power, Kindness, and Mercy—the Most Kind to His creations, so He shows them the benefits of and enlightens them with knowledge, and makes them understand the proofs. Also, He grants some people with more of the strange wisdom and the mystic knowledge[12] of the art[13] than He gives others, by the love He places in the hearts of those people—the people of knowledge—to the point where they seek their knowledge, and He further aids them, through the sin and weakness He takes out of their hearts, a favour from God—the Honoured and Glorified—upon them.[14] Then God—Glorified and Exalted is He—has granted this knowledge to some people by their paying the least of effort, and forbade some from Ijtihad[15] in seeking wisdom and knowledge of the art. For God the Most High has created nothing better looking, nor greater ending, nor more precious in the hearts of people, nor more rare amongst the people than the Fursan. And it is narrated by some Ulama[16] that they said "people are either a Faris or a scholar"[17] so we find them putting Fursan before Ulama. And more than that, there is the saying of prophet Mohammed (PBUH), "every entertainment a son of Adam[18] has is useless but training his horse, playing with the one who accepted him,[19] and shooting by his bow."[20] And it was narrated by Mohammed bin Isa,[21] that Abu-Bakr bin Alharith bin Abdulrahman ibn[22] Makhool[23] said that the Prophet (PBUH) used to include Fursan and the people of Quran amongst his close companions.[24] And it was narrated that Mohammed ibn Isa ibn Younus,[25] said Osama bin Zaid[26] narrated that Makhool said, Omar bin AlKhattab[27] wrote to the people of Homs, telling them to teach their kids Furusiyah, swimming, and shooting with arrows,[28] and command their children to learn how to hide amongst different things.

|

[2v.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 2v.jpg [38r.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 38r.jpg[29] | |

And Furusiyah has fundamentals none of them is enough by itself, and each one branches into many meanings, and no Furusiyah of a man is complete until he knows these meanings and fundamentals. And the first fundamental—which is the head in that Furusiyah is not complete until this is well fixed—is the Faris's goodness, riding, his horse, being firm, being excellent in holding the reins of the horse, and knowing what kind of animals is best for each art of Furusiyah, as he might need different animal in creation and riding[30] for each part. And the second is fineness, knowledge of weaponry and how to deal with them, and causes that refine the work or damage it. Third is bravery, good administration of the art, and the strength of one's heart when faced by risks and fencing. Whoever has knowledge of the first two fundamentals is a knowledgeable, and whoever has all those fundamentals is perfect in his Furusiyah, and Furusiyah itself is within his hands—more than he with the two.[31] Yet if one was not brave by nature, he would not benefit much from his knowledge of Furusiyah. And know, that the origin and branches of bravery are Ihtisab,[32] believing that patience is attainable, knowledge of your rights and obligations, doing good deeds, diminishing what others would magnify, becoming patient when afraid and facing what the mountains seek protection from, and passing through the trails that exhaust others, all by the will of God. |

[38r.2] Page:MS Arabe 2824 38r.jpg [38v.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 38v.jpg | |

And the one upon whom God has granted the halal,[33] put this intellect in, and completed this knowledge for, should put himself in the obedience of God who has blessed him with this honorable way of life, and prestigious honorable art, and should put the intention of using it in the sake of God and fighting His enemies much in gratitude for God—the Honoured and Glorified—for what He has taught him of that, and should not give it[34] unless to the one who is mindful of God—the Honoured and Glorified—and is obedient to Him of the people of good intentions and good insight. And the one who wants to benefit of this knowledge should be patient in what he is asked to do and be humble to the one he is learning from, and God is the one who helps us and makes us successful in all matters. |

[38v.2] Page:MS Arabe 2824 38v.jpg [39r.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 39r.jpg

| |

| And know that if you do not hold the origin of a thing and its base, no branch shall get completed, and the base of Furusiyah is firmness, and the base of firmness is riding without a saddle. Who does not learn Furusiyah bareback, neither his riding nor his firmness shall be correct, and he would always be worried about his saddle, and he cannot be trusted not to fall if his horse trembles or a rise hits it.[35] As I saw some who claimed to know Furusiyah and the work of spears when they were not learned bare back, would fall from their horses at any problem coming from the horse from sudden stopping or jumping. And know that if a man is to have ten horses and an enemy attacked him suddenly and none of these horses has a saddle and he didn't know how to ride without a saddle, he would stay on foot and none of these horses would be of benefit to him. While if he knew how to ride without a saddle, he would have ridden, fought, and survived. We have seen some who survived bareback with a bridle, and some who, at the times of need, rode their horses with neither a saddle nor a bridle and survived. We also followed some Fursan who would throw the saddle to the hip of their horses once they realized the horse was getting inactive and then they would speed up and they escaped us. And not anyone who rides animals and plays with spears is perfect in their Furusiyah. Rather, the perfect firm, and fit Faris is the one who looks like he is still on the back of his horse, and the one who is free from flaws that strike the Pursan who deal with this matter poorly, as most people who ride animals and make them run fall down. So start with learning how to ride bareback and do not be ashamed as you seek closeness to God—the Honoured and Glorified—and seek a noble way, of which so many people are incapable. Don't you see that so few people are seeking that this become their status? And depict in yourself that there is no status higher than the status of he who masters this science and in God are power and success. |

[39r.2] Page:MS Arabe 2824 39r.jpg [39v.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 39v.jpg | |

So if you want that, put a bridle on your horse, and tighten a jull[36] to it that is made of fleece or fluff which has a strong Jafa and Lubt[37] as the Faris is firmer on a jull than he is on a plain back. Then stand at the left side of your horse by its shoulder while your crop is in your left hand, and put the thumb of your left hand in the Lubt of the Jull at the top after you attached the rein to your thumb and the palm of your hand is on the horse's shoulder. And jump and grab its neck with your right hand from the side and catch it, and use it to mount. This is the best and easiest way to ride on a naked horse, which if you achieve and get firmly, you would not need the jull anymore. And if you take the bare hair of the horse, along with the rein in the left hand it is fine, but not every horse has a mane. And the first method is more beloved to me, so if you are on the horse, hold the rein with both of your hands and put them at the withers of the horse, straighten your back, and hold with your thighs the sides of the horse and move a little forward on its back as it is better on naked horses and is firmer, and stretch your knees forward with your legs to the shoulders of the horse until you can see your big toe, and depend on nothing but your thighs in getting firm on the horse as stillness is only correct through this position, and everyone who does not depend on it is not firm. So walk anaq for some days until we know that you have ridden firm, then then go soft Khabab until you are settled with it, hold and protect yourself when starting Khabab and then increase in your Khabab until you come close to Taqreeb.[38] So if you were settled and used neither your legs nor your feet to help you settle, did not get them under the arm pads of the horse or in front of it in Khabab, and did not fall from the horse, in this case proceed to Taqreeb and make your back and riding as I described to you concerning the two fundamentals. So if you stayed firm, get your horse out onto firm ground,[39] then delay and stay behind afterwards and get it to rest and protect yourself. |

[39v.2] Page:MS Arabe 2824 39v.jpg [40r.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 40r.jpg | |

If you mastered riding bareback, in the way I have described for you, God—the Honoured and Glorified—has guided you, by His generosity, to own the origin of horse riding and the largest part of Furusiyah. Then take a light tool without a cover,[40] uncovered, and take a Baziki bridle and nothing compares to the Bazikis as they are the bridles of Fursan and they get you busy as it is two pieces so whenever the horse wants to go running while the Faris is riding, it cannot get used to the Baziki so it slows down and it does not like the tightness of the Baziki. And you would not pass anything in crowds but it will stick to the horse's mouth, but the kings took it for its beauty and to use in the hippodromes. It is a good bridle for the urban areas, but I have seen some animals while ridden with the ordinary bridle better than when they are with the Baziki. And what is needed in terms of firmness, and trueness, and lightness in traveling, then it's the Baziki. However, the lightness and heaviness of a bridle is based on the amount an animal can afford, as there are among animals those that can afford the heaviness of a bridle, and among them the weak-jawed ones that cannot afford the heaviness and would sag and stop before they are commanded to, and this would cut the animal from its nature and liveliness. So put on it whatever it can afford, by the will of God the Most High. |

[40r.2] Page:MS Arabe 2824 40r.jpg [40v.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 40v.jpg | |

And use on the bridle a pair of throatlashes and make for the throatlashes a lead of thong or a rope and tighten it under the jaw so the animal would not take it off by shaking its head, nor would your enemy take it off as he sees it the most powerful thing to do and use an iron bit as large as your horse can afford of the width and tightness in the bridle. And if you want, while traveling, take a bit with a feedbag[41] that does not leave your horse on which you hang its barley and water, so it is a bit and it is a lead at the same time, and the people of cunning see it as a must, unless the bit is attached to the lead of the bridle, for when it becomes a halter and it is spared from getting cut, and it is needed to ride fast, your bridle will not be on the bit for one of them is not attached, the horse would open its mouth and not close it and it tongues the bit and buries the bit under its tongue. And whenever it does not do so, it will not be spared from blood and with what the thing but with blood. And do not let your bridle be without a leash for a quick or flighty horse,[42] which uses an onshotah[43] and a light node, or put it in the saddle between the qarboos and meytharah[44] so it will be faster to respond to him if he commanded it to slow down at the time of traveling, but at the time of war and fencing, tie it to your waist—meaning the lash—for a Faris is not safe from falling and if it is not tied to his waist his animal will run away, and if it is tied he succeeds. |

[40v.2] Page:MS Arabe 2824 40v.jpg [41r.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 41r.jpg | |

And take a firm saddle, of firm wood, and wide seated, excessive in speed, thick in its front and back qarbooses, and verily the Arabized peoples have made those high qarbooses so they put their belongings on their saddles which become like extra hands. But if the qarboos is too high, the Faris cannot move the spear as he wants, and his riding and sitting in the saddle become as ugly as if he was sitting at home, and whenever his animal stumbles he is not safe from the qarboos hitting his chest and abdomen which will make him weak. And take a thick cinch and a thin cinch, but if it is only one strong cinch that is going around the whole saddle it would be firmer. And take a strong belt and two stirrups moderate in weight and rings neither too wide nor too narrow, and ensure that the bottom of the stirrup is punctured as it is firmer for the foot, and their heaviness is firmer for the feet, for the stirrups may get off the feet of the Faris, and he wants while running to put his feet back in them. If they are too light, he would not find them, and if they are very heavy, his foot will find it whenever it looks for it, and his foot does not hit the stirrup away, nor does it wave around. And be sure of the stirrup leathers, and check their length and shortness so they are one size, and they are at the size they are needed to be, and their proper size is when they hold the feet up while closer to being high is better than being too low because when the stirrup is low the Faris is thrown when his horse jumps or stops, and he is not spared from falling when his horse rears or trips. With what becomes ugly of his riding; his legs with bended knees on the sides, or his legs being in the back, he—in this way—is not safe from breaking the back of his saddle when his horse jumps. And take a good squared set of labood[45] softly stuffed, or a nice and circled as it is from the art of Furosiyah and it is fit for the hippodrome. |

[41r.2] Page:MS Arabe 2824 41r.jpg [41v.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 41v.jpg

| |

As for the saddle pad for battle, it needs to be wide so it covers the hips of the animal, and the squared one is more beautiful for the Faris and better, or two circled badads,[46] as the long badad for its lightness and being fast-to-put the saddle on is better and safer for its withers and strap if the Faris is always on the back of his horse for if one of the straps of the badad is cut while riding, the front and back qarbooses slip to the far back of the horse, so change it to having a lubt mershahat[47] cloth to arches sized for protection under the badads so whenever a strap from the straps of badad is to be cut making it defective, the mershahat under the saddle is a protection for the back of the horse, and it dries the sweat from getting to the badads. |

||

So if you mastered what I described to you from your tools and your horse's tools, and have put the saddle on your horse, you tie the belt of your horse yourself. And if it was done for you, test it upon riding for you are gathering in this some matters in precaution of the firmness of your saddle. And if the belt is tied, and the saddle did not move on the back of the horse, you cannot change it, and whenever the belt was loose and you depended on it in the time of riding and you had a weapon, the weapon will tip the saddle. So if you want to ride, stand to the left of the horse, your whip is in your left hand by the left stirrup and hide it a little, open your clothes,[48] and then grab the reins by your left hand along with the mane, and if the horse does not have a mane, then grab the arch of the qarboos from the inside. Then turn the stirrup to the front one turn, then put the front of the sole of your left foot in the left stirrup and stretch it to the shoulder of the horse, and do not push it into the abdomen of the horse, then take the back qarboos in your right hand and carry yourself up nice and slow in a neat, prestigious, fit, and calm way until you ride. If you are settled in the saddle, put your right foot in the right stirrup then open your clothes. If you like fixing your clothes with your right hand before sitting on the saddle and after mounting, then do so as the fursan do so, but I do not see to doing this, as you should get your hands grabbing the saddle until you ride and get settled in your saddle, then you fix your clothes. And shorten the reins from the right side a little while riding so it does not drive the stirrup away from you and if it moves it will come closer to you. And if you want, grab the back of the saddle with your right hand while riding and this is all fine except that taking the front qarboos with your right hand is more beloved to me because if the horse jumps while you want to ride it and your right hand is grabbing the front qarboos, it will not release, and of it was grabbing the back, you would not be spared from missing your ride. Then take the reins with both of your hands and fix with it the head of your arch. |

[41v.3] Page:MS Arabe 2824 41v.jpg [42r.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 42r.jpg | |

And know, that the pillars of Furosiyah are the goodness of holding the reins, firmness, and labaqat. As for labaqat,[49] it is the goodness of the attributes of the Faris, the goodness of his stature the goodness of his setting himself upon the saddle, and of the relaxed position of his legs and arms. And the goodness of setting himself upon the saddle is that he sits upright and straight, neither loose nor moving, and do not lean to the front in an ugly way. And the tips of your feet are in the stirrups, and stretch them to the front but do not excess in that. If you are settled in your saddle, fixed your clothes, and got the reins in your hands in front of the Qarboos on the withers of the horse, holding its head up with your reins, and if there was extra length in your rein you fold it in one of your hands, between your hands. And the reins can be long in this place if he was not working with a spear or if the horse could feel the reins.[50] And do not excessively loosen up the reins of the horse which gets it confused and anxious. Then go out for walk, and let your way of getting your horse going be by spurring it with your heel bones, do not bend as if you would hurt it with your hands, and do not move your legs and hit it in its abdomen as most of people do which is ugly and Fursan do not do it. Then walk in the Anaq pace well and nicely in the slowest of the Anaq of your horse. And be as I described to you of this matter, and straighten up your shoulders and back like God created you, straight not bent. And do not lie down, and get well settled in the saddle. And hold with your thighs the sides of the horse, and check your legs, and your feet in the stirrups and keep the soles in them the stirrups. And do not open your legs or get them to the back as nothing in the Faris is uglier than getting his legs to the back. So if you mastered what I have described for you, commit yourself to it and thus becomes your nature and habit in Anaq walk and you mastered the riding as I described to you and nothing happened but what is right, and you never did move but with elegance, then bring your horse to the Khabab by poking it with your heel hone as I described to you as until the Khabab gets difficult and can almost take the Faris off the saddle. Then get your horse to Taqreeb moderately in a slow Taqreeb like the walking on foot with your horse being calm as well as you on its back. And you loosen up the reins until (...)[51] get confused and then meet up and it does Taqreeb like this completely. Then get the horse to its left side back to how it was from being calm and relaxed with the Naward[52] being wide, and let the Naward be between 70 to 80 feet wide for when the Naward gets wider, it becomes calmer and more relaxing to the horse[53] and more relaxing to the Faris on its back, and its steps become firmer on the ground while if the ring was tighter, the horse gets confused even if it was smart and strong-hearted, and there is no goodness in what is not strong-hearted among horses. And the fear of its own hooves, upon tightening the ring, comes and the horse will not be safe from slipping and making mistakes. And now, the tightening of the Naward and the quickness of turning when it is needed with fencers: And the Naward has conditions and causes, and the same thing I see that the wall of your Naward; a balanced circle no doubt, rounding it up in one way and a boundary, and if you wanted to turn, you get a little off the wall piece by piece, and then you turn to the right which is faster for turning and it is needed to be gotten used to by you and your horse; and thus the Naward must be wide.[54] |

[42r.2] Page:MS Arabe 2824 42r.jpg [42v] Page:MS Arabe 2824 42v.jpg [43r.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 43r.jpg |

Illustrations |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Now the military maneuver and what comes after it; a branching of all the maneuvers Next comes the Bunood[55] and Tasareeh[56] which are seventy-two Bands. |

||

The first of them is a Military Band: [one] holds the lance in his right hand and moves to the left then to the right, and throws the head of the lance to his back on the right and then moves it—and like this succeeds—and releases to the end of the lance then he holds on to the qarboos[57] and stabs back and forth, in and out, then move [the horse] left with a Zandyiah.[58][59] |

||

The Second Band is the band of Ali may Allah honour his face: twist Hamaili[60] on the right shoulder, hold it tight [in both hands] with a grip like a hawk,[61] in and out with tasreeh and a Zandyiah.[62] |

||

The third Band is the Band of Hamzah may Allah be pleased with him, hold on to the qarboos and stab back and forth and throw the lance to the back of the right shoulder and move it to the left and do a Zandyiah.[63] |

||

The fourth Band is the Band of Khalid may Allah be pleased with him: stab and hold on to the qarboos heroically,[64] take [the spear] to the front by three rings and throw it left and get back with Zandyiah.[65] |

||

The fifth Band is the Jahilyiat Band:[66] Hamaili on the right shoulder, and get back uncovering, then get under the armpit and hold on to the qarboos, and stab in and out and throw to the left and a Zandyiah.[67] |

||

The sixth is the perfection band: stick[68] to the front and deliver [the spear] to the left on your left shoulder, then strike upward[69] and hold on to the cantle and stab out and in and throw to the left and a Zandyiah.[70] |

||

The seventh is the stirrup Band: stick to the front leaning on the right and wheel to the right with an upward strike, then wheel left, holding to the cantle and stabbing and throwing to the left and a Zandyiah.[71] |

||

The eighth is the Neckless Band: stick to the front, and wheel left and take a Zandyiah. |

||

The ninth Band is like the seventh with the addition of a left wheel[72] |

||

The tenth Band is called the Band of Service which is the Band of Talhah Turn Hamaili on the right shoulder concurrently with releasing half of the lance backwards on the back of your right shoulder and the head is to the front, and grab the lance from the top and then move it to the left and hold it from the middle on your left shoulder then grab it with your right hand and hit Dubooqah until it gets to the left, then raise your chest to it until it passes by it and go then move to the left and get back with a Zandyiah.[73] |

||

The Eleventh is the Band of Alzubair (may Allah be pleased with him): Hamaili on the right shoulder and hold straight, upon landing release, hold on the qarboos, stab back and forth, hit to the left, and get back with a Zandyiah.[74] |

||

The Twelfth is the Band of AlMustas'ib which is the colouring: turn Hamaili on the right, hold your hands together,[75] do a Dowlab to the left, then get back with a Zandyiah and do what you do in every Band. |

||

The Thirteenth, is called The Perfectionistic:[76] turn Hamaili, wheel to the left, then get back with a Zandyiah, thus do what you do in end of Bands. |

||

The Fifteenth, sticking to the front, and leaning [the lance] on the left shoulder and circulating it in your hand, then you get down with your right hand to the back while the lance in your hand behind your back, then take it with your left hand and hit Dubooqah with your right hand and you do what you do at the end of Bands. |

||

The Sixteenth is called The Split One, turn Hamaili, hold straight, and do a Dowlab to the right, a Dowlab to the left, then hold it Maktoof, hardened, from your left shoulder, and you do what you do at the end of Bands. |

||

The Seventeenth is called Kowr Tareh: stick the head |

||

The head of the lance staying[77] straight and you hold it with your left [arm] and you deliver the rein to the right [hand], and hit its [lance] back with the right side of your neck and deliver the rein to the left and hold the lance standing up and hold on to the cantle and stab back and forth, in and out and throw it two Taqs[78] and hit to the left, and get back with a Zandyiah. |

||

The Eighteenth is called the Hall and Aqd Band: turn Hamaili meeting the Maktoof with hitting the right side, hitting Dowlab on the right and do what you do with the rest of the Bands [i.e. Zandyiah]. |

||

The Nineteenth is the Band of Dhirar binAl-Azwar (may Allah be pleased with him): Hamaili on the right Maktoof with a Dowlab to the right and left, get up and hold on to the cantle, stab back and forth, out and in with the [lance extended] long and do what you do with the rest of the Bands. |

||

The Twentieth Band: turn Aqbyiah[79] Zandyiah in front of [your] hands, with a Dowlab to the right, hold on to the cantle, stab back and forth, and get back with a Zandyiah. |

||

The Twenty First, the Kowr BirKhan: turn and sit to the front and take [the lance] Maktoof and to the left stay with it to the front and hit Dubooqah and the tenth[80] Dowlab to the left shoulder while standing and do what you do with it what you do at the end of Bands. |

||

The Twenty Second is the Sword Band: Aqbyiah Zandyiah staying straight holding [the lance] to the left and doing Kaffyiah[81] with the right hand and you get it down behind your back, and hold it with the left and unsheathe your sword and sheathe it back and hit Dubooqah and stay tenth then another Dubooqah and you hold the lance opposite to your shoulder like you are stabbing with it and hit Zandyiah.[82] |

||

The Twenty Third is the orphan Band: Aqbyiah, Zandyiah turn Hamaili, Maktoof staying tenth and hit Dubooqah, right turning Dowlab, and do what you do. |

||

At the end of the Bands, the Twenty Fourth is called the two services Band |

||

Turn Hamaili then Zandyiah then release it to the left and serve by your right and then hide it behind your back by your left hand and give it to the right and serve by the left and that's why it was called the two services Band and the description of the form of service is as one does to the spectators, which is to greet them and [salute],[83] then you sit with it to the front, then you hit Dubooqah with staying tenth, then you receive it with the right over your left shoulder from its opposite [side] and you do what you do at the end of Bands. |

||

The Twenty Fifth is the Band of the Mixed; which is to turn and hit with the head of the lance on the left side of the neck and receive it with the right and you do Zandyiah with your left then you do what you do at the end of Bands. |

||

The Twenty Sixth is the Band of Al-Taq; turn Zandyiah and stay to the front then hit Kaffyiah[84] and you do it in Dubooqah and you hold the lance, standing up, from your left shoulder and hold onto the cantle and stab back and forth then retreat and get back in and get in and out as well in the tall one[85] then release to the right on your shoulder to the back to the end of the lance. When you reach the end of the lance, hold onto it with your right hand and throw it from below upward, spinning it so that its head comes to your hand and then release it and get back with Zandyiah and do what you do at the end of the Bands. |

||

The Twenty Seventh is called Jamillah and it is the Band of the beauty; turn Zandyiah and bring it through the turning of the Zandyiah making it on both of your shoulders spinning by itself and you are centring it over your neck for two or three times then let it get down from the back saddle parallel to the spine[86] then hold it with your left and move it to the right with a jump while holding onto the cantle etc. and add to it getting in and out with the tall one. |

[12v.4] Page:MS Arabe 2824 12v.jpg [13r.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 13r.jpg | |

The Twenty Eighth is the Band of the Elyaki, turn Hamaili then hold it Maktoof and followed by the left like you do in the hardened, then do a left Dowlab holding it from above your left shoulder with your right hand Maktoof, bend it, and get it followed by the left bending it like the first. Then release it to the outside and then you do what you do at the end of the Bands. |

||

The Twenty Ninth is called the collected, straight and outstanding with no retreat, give it to the left and take [it] with the right Dubooqah again and make a right Dowlab from any Dowlab going to the left receiving it Maktoof inevitably urgent. Turn to the front and then Kaffyiah Dhahryiah[87] then give it to the left and take it with your right. Then hit Dubooqah then right Dowlab then Zandyiah then left Dowlab then receive it Maktoof with your right hand and hit right Dowlab then Zandyiah then left Dowlab then receive it Maktoof by your right and hit right Dowlab, Zandyiah, hit left Dowlab, and stay tenth then release, hold onto the cantle, stab back and forth, and throw two Taqs upside down and then throw heroically then stay straight and release and get back with Zandyiah. |

||

The Thirtieth Chapter is the Band of the accompanied, Aqbyiah Kaffyiah with descending under the armpit, move it to the left, and then do what you do at the end of Bands. |

||

The Thirty first is the seeking company Band. |

||

The translation which follows is a selection of those sections of Jāmiʿ al-funūn most relevant to the study of swordfighting and the development of the saber in the Islamicate, prepared by Hamilton Parker Cook, PhD, for the Oakeshott Collection.

Illustrations |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

You should put in the shield two, delicate (liṭāf) rings between the two edges of the inner part of the shield (min al-khānabayn). Then, you should add a fine cord (bindan latifan) to them. Then, you tie a knot to the head of this cord, which should enter over the right shoulder over the gambeson (qarqal) and then should enter through the other side of the two rings, from under the grip. [The rider] should enter his right hand from under the cord between the grip and one of the rings, and lift the shield over his (left) shoulder so that it protects and shields his face, and sets upon his [left] shoulder bone (ʿalā rummānati katfihi). He should then pull the rope tight such as he is able, then tie over the other ring one strap from the front. The rider should be able to transport it in this way, such that the shield does not move about while upon his shoulder whenever he intercepts a blow. If he wants to shorten the rope to make it tighter on his back, he should move it and shorten it between his shoulders. If the rider wants, he can return it to its (previous) position on his shoulder (from the back). If someone should bind a weapon to the shield, or thrust into the middle of the shield, the rider can cut the knot tying together the strap, and the shield will release, and the rider will be freed of it. None have seen a shield of this likeness before. Some of those who use shields when they seek to bind against a spear, they are not able to fire a single arrow as a riposte. With this shield, you are able to shoot whatever you want and thrust however you want, and the shield will not deter you at all. For this reason, riders have made these shields (in the above manner), and chosen these shields over all other shields. So you should not favor any other one, because this kind of shield will remain as the best. |

Illustrations |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Chapter Concerning how the Play of the Canes are on Foot It is that which consists of taking[88] and parrying.[89] If you will engage in this, you should:

|

||

Then your opponent should do as you have done. |

||

Then practice the known counters[94] to these actions between players of the cane. |

||

In this manner one should do as I’ve described to you here on horseback, if you intended to do the play on foot. |

||

Description of the Cane that the player should use It should only be from the bitter almond tree,[95] because it is not too stiff when striking.[96] Or, it should be one that can be made from an orange tree.[97] It should be one whose length is eight hand grips.[98] |

||

Now, the play beings with the stopping of the horses, and grabbing the cane in the rider’s right hand. The left stirrup should be short, in order for the rider to stand up in it. The rider should grab the reins of the horse at the half. After saluting the opponent,[99] the rider should begin by striking from the right and from the left, by breaking the trot of the horse[100] with the spurs—but not stopping the horse during any of the actions. The rider should circle in the Nāward.[101] |

||

Then: The rider should grab the horse by the head, and have it circulate. This is knowledge from the Chapter of Warfare.[102] The rider has already voided the opponent, after parrying him, from the right and from the left. Then, the rider should jump in a way to disengage after having grabbed the face of the horse and the flank of the horse. Then the rider should disengage from the right and the left. After disengaging, he should strike at the head. After striking, he should invert his cane so that it is behind him, and cast it to hit the two elbows, two times and three. Then, the rider should engage from the Abode of the Arm,[103] striking from the right and the left. Then disengage, inverting the cane to hit the two elbows, striking from the right and from the left. Then, he should strike from the right and the left. Then the rider should engage from the Abode of Entering:[104] he should lean in and strike from the right and the left. He should “strip” the opponent’s cane with his own cane that will lay on top of it.[105] Then he should cast the cane at the face of the opponent vertically[106] Then, the rider should turn his hand to strike under the armpit[107] of the opponent. Then, he should invert the cane threatening the head. Then, he should parry right and left, then enter to take advantage of the pursuit during retreat.[108] |

||

And strike three strikes: at the back of the neck, at the face, and the head of the horse. |

||

The way in which the play with the cane is done on horseback |

||

In direct confrontation and during the pursuit |

||

A description of this: One plays as one played on the ground It is necessary that the horse be obedient during all of the leanings, entries, and escapes. |

||

Some deceptions in executing the play of the cane: if you strike to the right, then invert the cane to threaten the hand quickly from the left. |

||

Another: If the opponent struck hard[109] against your cane, and you have also struck hard against his cane, then strike his forearm quickly from under his own cane. |

||

Another: If the opponent comes to you from «The Abode of Retreat», and he is unaware, lean on the shoulder of the horse to the right, and strike his face.[110] |

||

Another: If the opponent comes to you from the «Abode of Retreat» and has struck your cane, be yourself someone receptive to the strike.[111] Then immediately enter your hand from under your own cane and shackle up the opponent’s cane and pull it from him towards yourself—in order to take it from his hand. Whether it leaves his hand or not, do not busy yourself with taking the cane too much. Rather, invert your own cane toward the opponent’s neck quickly. This will yield a great injury. |

||

Another: If you want to have the opponent not reach you with his cane, then every time he attacks you from the Abode of Retreat, let him slip by, then lean to the right, always. He will not be able to reach you. If you want your strike to be strong, and want to stop his hand from striking, whenever you riposte with a strike, twist your hand in the blow, the opponent’s hand will become stung up unto the shoulder, and he will not be able to meet you [for another blow], and will fatigue. He will not be able to meet you [for another blow]. Then, [strike] three blows: If you strike, invert the blow, then invert the blow a second time from above, then strike a third time with your hand vertical.[112] This will yield a great injury. |

||

If the opponent should enter into a retreat, it will tire him out. |

||

A description of the play with the cane and the buckler on foot |

Illustrations |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

A description of the play with the dagger.[113] In our times, it is not common. |

||

Explanation of the Play with the Dagger. Its description is that you stand opposite the opponent, and put the right foot to the front, while putting the left foot behind. Grab the handle of the dagger with its head inverted toward the earth. Its pommel should be gripped so that the hand is showing outwards. You should seek to hold onto it well. If the opponent throws a blow against it, so that it should meet the reverse of the dagger, the meeting of the dagger should always be with the reverse of the dagger in all actions.[114] Your dagger should meet his own from the right and from the left, then shield the head with the dagger, and seek to riposte to the head of the opponent quickly. The person doing this should not do so excessively, nor should the players be neglectful in practicing, so that someone should die or be forced to retire. If you do this one time during a session[115] with the opponent, and if one should be able to reach the head of the opponent a second time, the player should take the back of the dagger, invert it to threaten the forearm and then take the dagger from the opponent all the while cutting his hand. This is indeed the art. If one does this exercise excessively, then it is possible to practice taking the sword or the knife from the opponent. Understand this, for it is a concise summary. |

||

Section: Concerning the Play with the buckler and cane.[116] The description of this is that you take up a light buckler and a cane[117] with a color of burnt wood.[118] The player stands holding the buckler in his left hand, and the stick in his right. He strikes the first strike at the face of the opponent, and then inverts the cane to strike under the opponent’s armpit, all the while not having the cane pass to become caught in the underarm itself—the opponent will be able to fend it off. The player should then extract the cane [from a bind] quickly to strike the hand of the opponent and his face. Then he should return the cane to above his head and strike at the face of the opponent. |

||

These are the three places of striking[119] on which rest the tradition[120] in its entirety. The one who understands the tradition’s ways of entering, its ways to retreat, its disadvantages, and its benefits, has come to know the entire tradition. |

Illustrations |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

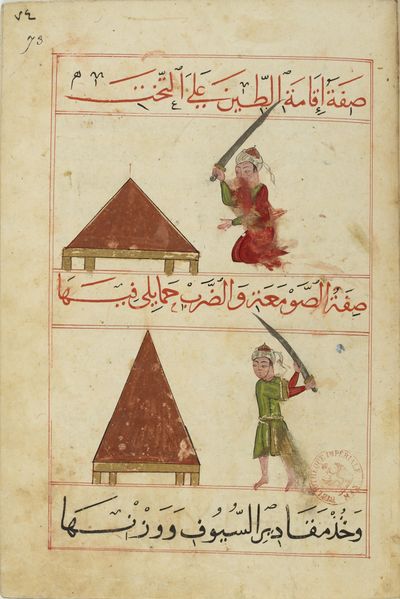

Chapter concerning Striking the Sword in Clay in Continual Training[121] It is necessary for one who wants to train striking the sword to make use of three swords, one light, one of middling weight, and one heavy, all from black iron.[122] His grip should be full in accordance with the strength of the palm of the one who is striking. If the striker practices striking with the first sword, he moves on to the second heaviest, then to the third. The weight of the first is three ratls, the weight of the second is five ratls, and that of the third is in accords with the strength of the striker.[123] If the person wishes to practice, he should begin by presenting clay that he has covered for two days or three. When he has covered it, he should take a plank of wood about the width of a coat of mail, and the length of five[?], and set it upon four small pillars, with each pillar being as tall of a handspan. The striker should also have something that can carry water, and a cutlet[124] of camel or cow, and some iron. Whatever may attach to the sword of clay, wipe it off with the cutlet. When one has done all of this, bake the clay in a crossed baking, and carry it upon the aforementioned plank. If the feet of the plank should be longer or shorter than they should be, the palm of the striker will be ruined. The clay should be set down on the plank as a small mound, as the back of a camel, so that the strike will land correctly. If the clay is placed incorrectly from above, or if it is too fine below, this will ruin the cut of the striker’s hand, and will be loathsome to the exercise. This is a great secret which not everyone understands: the clay pile should be in the same height of the striker, neither higher nor lower. |

||

If it is higher than that, then the hand will gain the habit of stopping short, for the strike becomes a moment among moments.[125] If it is shorter than that, then the hand will gain the habit of striking too hard,[126] and lessening of strength. However, if one does as I have said, the striker’s blow will become heavy and strong, and the heart of the striker will be overjoyed. His strike will remain accurate. The striker will be able to work the clay from the first instance of hitting all the way through to the end, as I have described it. It is also necessary that one does not mix into the clay anything that does not belong, for it will corrupt it. The clay itself can come from any kind of clay, whether it is lime, small ground stones, or plaster. When you have shaped the clay, and recognize its goodness, the exercise begins after becoming aware of the states of the clay and sword. The cutter should stand at the head of the clay, and enter in [by turning] the toes of the left foot, and enter in a little bit with the left side in striking due to the strength of the force of the right side. When one does not do this, there will be no strength to the cut at all. |

||

Chapter/section on holding the hilt of the sword with the correct grab. This entails that you grab the part of the sword meant to be grabbed.[127] Grasping the sword occurs in several ways: The first[128] is that if there is a small curve[129] to the grip, then it will not cut. Know that the sword does not cut save by its tip—and by no other part. If there is a curve at the tip of the blade, then it cuts. If the curve is from below the tip,[130] then it does not cut. The established grip is one that is gentle, this is the goal. It should be neither too refined, nor done incorrectly. |

||

This pertains to the composition of the sword. Let the grip of the sword be circular,[131] not broad. For if it is too broad, the the sword will fall from the hand, and will not remain in place in a steadfast fashion. If the grip is too fine, wrap wax around it a bit. This is what needs to be done especially with «darkened swords». Practice will make gripping these weapons much easier, and progress strength and composure in using them. If the hand grip is too close to the crossguard, it is incorrect, and if too close to the end of the sword, it is too fine—it will cause issues in the hand of the striker, even if the striker is stronger in build. Rather, the grip should be small and subtle at the top of the hand toward the crossguard and while robust yet not excessive toward the end of the sword. For if strength is applied to the front of the sword in cutting, the sword cuts well. If strength is applied to the back of the sword in cutting, the sword misses its mark,[132] and will have no strength in any cut that should happen. In addition, the grip should not bee too short, for then one could not strike with it. Rather, the whole sword should be manipulated from the end to the tip of the blade if it is held [well] from the grip. The right hand should twist well around the back of the grip, while the tip of the head of the sword should come towards the nose of the striker (in length). Whether the striker has two long hands or two shorter hands, the sword should come up to about the left eye. Many people who forge black swords broad, while making swords for striking fine. Between these swords are many differences. |

||

The broad bladed sword cuts deeper than the fine bladed sword. However, the fine bladed sword cuts more quickly than the broad bladed sword. The root cause of this lies in the grips, proper positioning, and in their quenching—there is no fourth reason. Quenching comes in many different varieties, while sections of the sword occur in different kinds. As for sword without quillons, its kinds are comprised of two different general varieties: "rigid"[133] and "soft-rigid".[134] The rigid part of a sword is made of iron and all things associated with it. The soft part of the sword is made of materials like crocodile and all concomitant with it. If we recall these two kinds beyond all others, it is because iron is a core part of making a blade as well as crocodile (or other biological material). An iron-wrought sword must be made from blue-green steel, and likewise when it is struck by the blacksmith it must be said about it "a sword shall be made with an edge".[135] There is an exception for those swords that do not have edges, such as the horseman's sword[136] which itself lacks an edge. As for the sword that cuts soft things, it must be made from white steel, and must at least have an edge as we’ve discussed before. It can also have a slight curve at the tip, the curve can also be more pronounced.[137] As for the grip, as we have said above, the strongest soft things to wrap around it are those that emerge from the water, such as the crocodile and other creatures. Another strong choice would be grips made from birds, ostriches, eagles, scorpions—great Egyptian vultures are by my reckoning the strongest of all. After these kinds, there are those made of sheep, donkey, and cow, and other such animals. Every one of these wrappings has a quenching, preparation, working, and fashioning—so understand this! |

||

If you desire to take up using the sword correctly: Stand as you have learned and take up the sword with the right hand. The shoulder should open up, because this gives the greatest power. The grip should be aligned with the back of the spine of the sword. You should place the top of the grip[138] between the thumb and the pointer finger without having the grip lean on the bones of the thumb and forefinger. |

||

The head of the grip should be freed to move about[139] between the two fingers to the top of the right quillon—just like thread. This is the right kind of wrapping. If the one meant to grip the sword grips it, he should raise his shoulder until it is at the same level as his ear, and raise his elbow in front of him. His left hand should be at a safe place. Once he has raised his elbow thusly, and is standing at the head of the striking point of the clay, he should bring the sword down in a balanced manner.[140] While doing so, he should be wary of his grip. The hand should not become lax in the grip. If this should happen, the sword will cut crookedly in the clay, and this will damage the hand. When the trainer goes to bring the sword down on the clay, he should do so with strength, and aim to make a cut on the right in his descending cut. When he does cut downwards, let his descending cut end in a draw back towards the cutter a bit. Were the cutter to cut a descending cut, and would not draw the sword back in this manner in his descent, he would not be able to cut anything effectively—neither would the sword be able to go through the clay. Let the cutter be on his knees when he cuts as well. |

||

This indeed is the secret to cutting efficaciously: Cut a downward cut. If you have cut into the body of the clay pile thoroughly, pull the sword toward you and then extract it from the clay. Do not lift the sword back toward the place from which you have made your descending cut, for it will become stuck in the reverse part of the clay, and the sword will bend in it. If clay sticks to the sword, take the cutlet that I mentioned before to you, wipe the blade off and clean it. Were you not to continuously work, and tire in the work of practice, the results of such labor will not come to you. Now, if you strike, strike the clay one strike at a time. Do so starting at the tip of the clay pile and work your way down to its base. Whenever you strike a bit of clay, move your legs forward a bit closer to the clay, until your strike cannot find space to work. If you have done this, and practiced these exercises thoroughly day by day, and have strengthened your shoulder, to the point that you have internalized this method of cutting into your very character |

||

Take up the second sword that is weightier than the first. Do what you have done with the first sword with the second—if you have the capacity to do so, and do not return to the first, taking up the second sword will strengthen you. Take up the aforementioned second sword, and when you have done as I have said to you, and have practiced thoroughly with the second sword, then take up the third sword. |

||

When you have practiced with the third sword sufficiently, and have become stronger, you may begin with the "Baldric Strike".[141] For this, you should construct a pyramid from the aforementioned clay. The bottom should be broad while the top should be thin, just as with the first clay pile. Its height should be at about your right breast. Take up the light sword with which you began your training, and stand facing the pyramid. Stand towards it with both feet flat on the ground, with feet equal distance from one another. Do not take a step yet. When you do step, one step should be ahead of the other, let your feet not be parallel upon the ground—this will corrupt your stance for cutting well. When you have taken a step [with the right foot], stop with your left side at an angle forward. Cast forth your sword from the left, and strike at the top of the pyramid from the left [with an ascending cut]. When you have struck from the left at the head of the silo, tread on the right foot with strength. Let your left shoulder assist your left cut [lean in with your body]. This is what is intended in this lesson. If you do not do this, you will not acquire any skill whatsoever in this Art. So strike from the left, and understand. Strike from the left section by section on the silo, until you reach the ground. When you have come close to the ground in your strikes, undertake descending cuts from the left, and attempt to perform drawing cuts in each cut. This is the correct tradition for striking. |

||

When you have finished this, that is, by cutting the left side of the clay, then take a goose and slaughter it. Hang up its body, and strike it from the left with the sword. |

||

A depiction of setting up the clay on the dais. |

||

A depiction of the pyramid of clay, and the Baldric Cut on it. |

||

In doing so, make sure to take the weights and measurements of the swords you will use in cutting the goose. |

||

And make sure to hang the carcass in in front of you in a place roughly at your breast level. Continue to cut from the left as you have done with clay. Your cuts from the left should stick to the spine in the back of the goose, and the goose should remain in two parts. Once you have considered yourself as having become proficient in these strikes, set up other pells to cut from soft-tissues. If you have not become proficient, return to the clay and strike it. However, if you have practiced well, string up another goose. Once you have cut these all down, begin with a sheep that you have sacrificed. Hang it up like you did the goose, but this time have the loins hung from above the head with its four legs hanging down, and its entrails opened. When you have become proficient in cutting the sheep, then move onto a donkey. Once you have become proficient in this, sacrifice a cow, hamstring it upon its knees after it has died, and hang it in such a way that its neck is exposed to you. Strike the neck in the same way that you have struck clay, and strike the flanks. Once you have become proficient at this, return, to the clay with a heavy sword, and then return again to this cow. Once you have become proficient at this, strike an ostrich. Once you have become proficient at this, then strike a vulture, and do not make light of it. Your strikes should be at its neck. Once you have become proficient at this, then strike a crocodile. In all of this there is great strength to be had. Do not refrain from cutting a carcass even if it is older or young. If it is young, do not fear, strike with steadfastness in your stance,[142] and seek to be proficient. If it is older, and has been dead for some time, do not fear, continue to strike. If one of these animals is alive, and it is hard to cut into them, in the case of quadrupeds, do not cut them unless you have thrown over their face a cloth. For when you strike at them, and they see the edge of your sword, it will tighten up, and such a strike will not be possible. However, if you put a cloth over their faces, their eyes will not be able to see. It will open its eyes under the cloth. Were the animal to become violent and lash out, at this moment, strike as you have hit the clay. Indeed, you will cut well. Once you have cut in this manner, it will be easy to cut any animal, such as beasts of prey, hyenas, wolves, bears, and beyond. |

[73v.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 73v.jpg [74r.1] Page:MS Arabe 2824 74r.jpg | |

Now, when you have struck something, your sword and its quenching will deteriorate. Indeed, there are many aspects to quenching. Do not [re-]quench a sword except with coal and felt. Now, if you are certain in your technique, you will try and cut felt from the left. A description: buy Syrian felt, wrap it up as you would wrap up a paper scroll. Arrange it as you had the pyramid of clay. Strike it from the left in the same way. Let your first left cut be twenty rolls of felt. Once you have cut twenty, then make it thirty. Once you have cut thirty, then make it fifty. Once you have cut fifty, then add ten layers of felt by ten until your strength becomes complete. At this moment, your sword with which you cut this felt should become whetted and sharpened, and should have breadth, in essence it should return to its original form.[143] Once you have done this, take up a bolt of cloth and place it over a stuffed carded-cotton cushion, and do not make light of this!. For many people cannot cut such a cushion. Strike at the cushion, and make your hand light, and keep your hand holding the cushion at a proper distance away from the strike. Indeed, the cloth will cut. |

||

Once you have done so, begin with strikes against iron. Now, it is necessary that you have at your disposal…[144] |

||

For every kind of sword cannot cannot be used outside of its class.[145] |

||

Chapter concerning cutting iron with the sword, and cutting all things that are rigid. This is [different] than cutting soft things. For this, you should have a sword possessed of a good edge as I have described to you. Take an iron bar and place it in the ground. It should be made of old horseshoes. Strike a blow in the correct manner. Be wary that the cut part does not fly into your face. If the iron bar cuts, and when put into the fire it glows, do not place it just anywhere, but rather, have your bars arranged well ordered on the ground. Doing this will strengthen you. You should begin, after this, what is called «trick cutting»—which is the cutting of ephemera.[146] This is a cut of various sheets from whatever one chooses by the strength of the sheet. A description of this: One can take a small cut of iron, formed into the form of a sheet that you can cut. One then adds to this a bit of starch to cover it and conceal it.[147] Once one has done this, no one from among those God has created would know what is in this sheet. One could then say to the crowd[148] "How many should I cut for you?" They would respond "this many, that many, etc." and then one could take up this bit of iron sheet, and add to it and place it before them in such a way that one could strike it, and the sheets would cut be cut just to the edge of the iron core, but the iron core of the sheets would not be cut themselves. They would perceive this with much wonder at the trick! I have not mentioned here many more such tricks. So understand this. |

||

A description of the practice of cutting reeds on horseback One should take a green, Persian reed, and then plunge it into the ground to about the height of the chest of the rider on horseback. Then the sword is grasped with vigor. You, the rider, should drive your horse and cut at the reed from the left, cutting it a hand-span[149] by hand-span to the extent that only a hand-span should remain. When you have achieved certainty in this, intensify your strike to that of wild game on the ground. |

||

Take care that the sword does not cut through the horse or through yourself.[150] Do not grab the sword except in such a way that leaves room for free movement at the right side of the horse. If you find that you are not hitting,[151] do not strike from the left nor strike in the same way you have been doing before. Rather, thrust a good thrust at the reed while standing up in your two stirrups. Refine your hand on the sword, and do not hurry, you will push through.[152] However, your toes should remain in the stirrups, do not release your toes to the side of the horse, or you will be expelled from the stirrups. Be wary of this. |

||

Depiction of the Green Reed |

||

Practice with the sword on horseback |

||

The reed and practicing on horseback |

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

| Work | Author(s) | Source | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| Images | Bibliothèque nationale de France | ||

| Translation | Meshari Al-Otaibi | HAMA Association Mamluk Project | |

| Translation | Hamilton Parker Cook, PhD | Wiktenauer | |

| Transcription | Index:Kitāb al-maḫzūn ğāmi' al-funūn (MS Arabe 2824) |

Additional Resources

- Agnès CARAYON, “La Furūsiyya Des Mamlûks: Une élite sociale à cheval (1250-1517), Doctoral Thesis in History (Arab World, Muslim, and Semitic Studies), Université de Provence Aix-Marseille, June 26 2012.

- Shihab al-Sarraf, “Mamluk Furūsīyah Literature and Its Antecedents,” in Mamlūk Studies Review Vol. VIII, No. 1 (2004).

References

- ↑ Pseudo Ibn Akhī Ḥizām, “Kitāb al-makhzūn”

- ↑ al-Sarraf, “Mamluk Furūsīyah Literature and Its Antecedents”, pg. 154

- ↑ CARAYON, “La Furūsiyya Des Mamlûks”, pg. 605

- ↑ al-Sarraf, “Mamluk Furūsīyah Literature and Its Antecedents”, pg. 155-172

- ↑ Pseudo Ibn Akhī Ḥizām Kitāb al-makhzūn, 2r

- ↑ Pseudo Ibn Akhī Ḥizām Kitāb al-makhzūn, 3r

- ↑ See: Pseudo Ibn Akhī Ḥizām Kitāb al-makhzūn, 28r, 36r, 62r etc.

- ↑ CARAYON, “La Furūsiyya Des Mamlûks”, pp. 567, 574, 581

- ↑ This entire opening, including its references to the Quran, can be understood as a sort of thesis through which the author purchases social credit through a display of religious relevance and piety and attempts to contextualize their art in the religious sensibilities of the time. The author does not include the reference numbers to the Quranic passages that he presents, but they would have been largely known by his audience.

- ↑ Furusiyah is an art of horsemanship or chivalry, deriving from the same root as "horse." Like Chivalry, its extent through martial arts on horseback and on foot, as well as religious and moral codes has changed over time and from one culture to another, however its distinctive practices set it apart from Chivalry as an art in its own right.

- ↑ The plural of faris; a practitioner of Furusiyah.

- ↑ Hidden intelligence, while the concept does not refer directly to Greek concepts of "the mysteries", it is an appropriate approximation so long as the reader is cautious to avoid Orientalist interpretations of mystical swordsmanship beyond what the author himself presents.

- ↑ The art of Furusiyah.

- ↑ The author puts effort here to dispel the magical in favour of a mundane approach to learning the art: God does not give some people magical knowledge of Furusiyah, rather He gifts them with passion and removes obstacles from their education so that they may learn it themselves.

- ↑ This term has great contemporary religious significance in academia, however here it means simply to exert effort, meaning some people are forbidden by God to seek knowledge in the art of Furusiyah as a way of explaining why some excel and others do not, not as a social restriction on learning the art.

- ↑ Scholars

- ↑ Similar to the phrase "if you can't do, teach."

- ↑ The sons of Adam; all of humanity.

- ↑ The one who accepted him; his wife.

- ↑ This quote is found in classical Hadith literature as narrated in many ways, but Tirmidhy narrated it from Abduilah bin Abdulrahman bin Abu-Hasan as, "Verily, God would let by one arrow three people into Heaven: its maker who is seeking goodness in making it, its archer, and its supplier, and "the Prophet' said shoot and ride, and for you to shoot is more beloved to me than to ride, every entertainment a Muslim man has is useless except shooting with his bow, training his horse, and playing with his wife for they are from Truth." lt is unclear why the author relates the Hadith in a way that excludes riding, when that is the focus of his work.

- ↑ Mohammed bin lsa bin Shaibah bin AlSalt bin Osfour Alsudousi, Abu Ali Albasri Albazzar. Died circa 300H/913CE in Egypt.

- ↑ Ibn, bin, abu, and other words are used in Arab genealogical names to identify lineage, which becomes important when relating oral traditions such as these. In this case, it is our opinion that a mistake was made in transcription or in fact, as the Abu-Bakr referred to here is a man well known to history, being one of the Seven Jurists of Medina, with a well known genealogy (his genealogical name is traditionally Abu-Bakr bin Abdulrahman bin Alharith bin Hisham bin Almugheerah). Makhool is largely regarded to be from a different tribe, and therefore not the ancestor of this Abu-Bakr. This mistake could represent an alternative genealogy, or an intentional or accidental misattribution or more likely, it could have been a manuscript error and intended as, "And it was narrated through Mohammed bin lsa, by Abu-Bakr bin Alharith bin Abdulrahman that Makhool said that the Prophet..."

- ↑ This is a narrator of Hadith that used to narrate traditions without the chain of narration that supports oral traditions, so his narrations are rarely found in the classical Hadith literature and are usually graded poorly. He was not present in the early Islamic period, but in this work the chains of narration end with him, demonstrating the gap in oral history between him and his subjects.

- ↑ This is likely a novel Hadith. Our team has not found it in any other source.

- ↑ This narrator is not known, but Isa bin Younus bin Abu-Ishaq Amro bin Abdullah, Abu-Mohammed, is a famous narrator and either the intended person given here, or possibly his father.

- ↑ The well known scholar Abu-Zaid AlLaithi.

- ↑ The second Caliph

- ↑ This appears to be a composite of several traditions. The first hadith was narrated by this the following chain of narration: Abu-Hatim Mohammed bin Ya'qoob told us, said Alhussain bin ldrees, said Swaid bin Abi-Nasr, said Abdullah bin Almubarak, from Osama bin Zaid, said Makhool Aldimashqi that Omar bin Alkhattab wrote to the people of Sham 'teach your kids swimming, shooting with arrows, and Furusiyah."' in the book of Fadhaeel Alrami for lshaq bin Alqarrab #15 pg. 55-56 and the rest (teach them to hide amongst different things) was narrated by Sarkhasi in the Alseyar, in the chapter of weaponry and Furusiyah.

- ↑ The original manuscript from which this translation derives has its pages out of order. The order was reconstructed through cross-referencing other contemporary works that cite or copy this work as well as through analysis of the themes, structure and grammar of the text itself. This page break is an example of one such reconstruction, as the following contents are misplaced to elsewhere in the original manuscript.

- ↑ This is to say a different individual horse or breed of horse, not a different type of mount entirely.

- ↑ The exact meaning of this phrase is unclear. It might be a copying error from a previous passage, or it might be intended as we have rendered it, or it might mean "...and Furusiyah itself is within one's grasp once they have the first two fundamentals."

- ↑ A state of patience or peacefulness, indicating a spirit of contentedness. The examples given in attaining 'bravery' belie a very distinctive paradigm in which the one who knows and exercises his rights, does good deeds, etc. can be content with his life, and therefore remove from himself all anxiety and face fear with stoic 'patience,' which is to say allow it to pass, rather than overcome it or pretend it does not exist.

- ↑ Literally, that which is permitted, could indicate any form of blessings including knowledge or material wealth which allows the practitioner the time and ability to perfect his art.

- ↑ Which is to say teach it, or indeed translate it.

- ↑ Through the passive nature of the horse, the author evokes the idea that the unsure rider is subjected to the terrain and not master over it.

- ↑ A type of saddle blanket or riding pad.

- ↑ These are archaic terms for part of the jull. Jafa could be a handle, or it could indicate that the jull is loose, as the word is related to removing a saddle or leaving one's place. Lubt is the belt or that which fastens the pad to the horse.

- ↑ These are technical gaits, though they are not always the most common terms for the gaits in modern terminology. The first, anaq, is walking. The second, khabab, is the pace, in which the left hooves and right hooves move together. The pace is uncommon in modern riding, however proves its utility in Furusiyah. The third, taqreeb, is galloping. The canter seems to be left out, as is the harder hodhor, which is a leaping sprint.

- ↑ Hezb, as found in the text, is usually translated as 'troops', rendering "get your horse out between the pair of troops." We have taken the meaning of 'firm terrain' instead because there is no other mention of troops or other participants in the text. This is a less common understanding of the word, and the meaning of the line is understood to indicate that the horse is to be taken out of the hippodrome and into the field.

- ↑ It is unclear what this tool is supposed to be.

- ↑ Roaimi Ethar, literally 'the lash of the people of Rome', which could refer to a tribe known as Roaimi, or the Byzantines, or a people who live in or near the Eastern Roman Empire. It is evidently a type of feed bag.

- ↑ The word mes'hak means very dark in all ways, rendering something like, 'do not let your bridle be without the blackest of leads.' Whereas we have rendered it assuming that the intention was mes'hak, which is a flighty horse.

- ↑ While in a modern sense this can mean a noose, presumably here it indicates a manger tie or quick release knot. In fact, the word in the text is written without dots, which would be isotah, but that word is meaningless.

- ↑ The qarboos is the cantle and pommel of the traditional Arabian saddle, which are much more vertical than in English or Western saddles, and may or may not include a horn, whereas the meytharah is the saddle cushion. The meaning here is likely in the case that the saddle does not have a horn, so the lead is secured between the cushion and the pommel.

- ↑ The ward is erased and from the text it is most likely to be labood and seems to be the plural form of the ward lubt.

- ↑ Badad is a big Lubt that is put on the back of the horse so that the wood of the saddle doesn't hurt it, it is taken from the word Badd which means the inner thigh due to the fact that this pad also touches the inner thigh of the rider.

- ↑ The sweat pad, from the root rash'h, meaning sweat.

- ↑ The style of clothing (probably the jacket), required opening before the rider could sit comfortably on the horse.

- ↑ Labaqat, from labaq, indicates perfection in the knowledge of doing something, and evidently needs a more precise definition in this context, which is provided by the author.

- ↑ Ibn Huthail cites this part and comments on it by saying that if the horse feels the reins it will know that the Faris is not focused and the horse will get used to driving itself.

- ↑ Damage to the manuscript prevents the interpretation of this word, but it seems to describe the instruction of the horse to abide loose reins.

- ↑ The naward is alternatively known as the manege, school or arena depending on its exact specifications.

- ↑ Perhaps this refers to the nature of the arena walls leaning outward while indeed blocking the path of the horse.

- ↑ This seems to indicate an exercise by which the Faris rides along the ring anti-clockwise, spiraling inward (thus moving away from the wall) as they become more comfortable with tighter circles. Once there is enough room between the faris and the wall, they can then quickly turn about toward the outside (thus their right side). Theoretically the exercise could thereafter be continued in the opposite direction.

- ↑ Bunood is the plural of Band which is "basic lance exercises or drills, intended to teach the student the basics of lance handling and riding, as a prerequisite to doing more advanced work in the hippodrome." The Mamluk Lancer, K. E. Jensen.

- ↑ Tasareeh is the plural of Tasreeh which is to release or to get out of the place. Twelve of the twenty-five Tasaree are mentioned somewhat cryptically at the end of this section, however the second band contains a tasreeh, which can be understood to mean a maneuver or guard.

- ↑ The word used here is Yuqarbis which is the verb of Qarboos. Because Qarboos describes the horn and the cantle, it is unclear which part should be gripped, so qarboos remains even though the word is in verb form, not noun form, in the original text.

- ↑ Zandyiah is a possession form of the word Zand which means the forearm, and here it means a hit with the forearm, however this more likely means to strike upward with the butt of the spear, thus presenting the forearm as the spear head goes over your left shoulder.

- ↑ This entire exercise can be understood to take place in a zig-zagging motion on the horse. The Faras will put his lance over his right shoulder and then throw it forward to allow his right hand to slip to the back, thus extending the reach of the lance. With the lance in the right and qarboos (likely saddle horn) in the left, the Faras will thrust to and fro before finishing with the Zandyiah as you move away to the left.

- ↑ K. E. Jensen mentioned that the word Hamaili may be a mistake and it originally means Carrying (Hamllan) since it was mentioned only once in his book. However, in this book it is mentioned many times by the same form which means it is not a mistake, rather it is a military term. In Arabic, when Hamal Ala comes in a military context, it means to fight hard, and by looking to the context here, one can conclude that the word Hamaili is an adjective for the verb Hamal Ala that was formed in accordance to the Egyptian dialect that was common around that time. In either case, the word seems to have fallen into use as jargon, since the sense in this book is that it indicates the spear or lance should be held in both hands.

- ↑ The word here is Muqarnasat which is used specifically for a falconer's hawk.