|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Gérard Thibault d'Anvers/Plates 1-11"

Bruce Hearns (talk | contribs) m (Minor title and description corrections) |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

| + | |- | ||

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

! Transcription by <br/>[[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Transcription by <br/>[[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 1,424: | Line 1,425: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | The practical point of this discussion on the concurrence of the Circle, the Sword, and the Human Body has been to show how easy it is for everyone to have a sword of the proper size. | |

| − | |The practical point of this discussion on the concurrence of the Circle, the Sword, and the Human Body has been to show how easy it is for everyone to have a sword of the proper size. | ||

But there is a concern about the permanently-inscribed Circle, wherein one must oftentimes test between people of unequal stature, for which each should have his own properly-sized Circle, or between people of equal size, but who are both either larger or smaller than the Diameter, such that the Circle is not drawn proportionally to their bodies. | But there is a concern about the permanently-inscribed Circle, wherein one must oftentimes test between people of unequal stature, for which each should have his own properly-sized Circle, or between people of equal size, but who are both either larger or smaller than the Diameter, such that the Circle is not drawn proportionally to their bodies. | ||

To minimize this inconvenience, the permanent Circle should be drawn to the proportions of an average person, to accomodate everyone. | To minimize this inconvenience, the permanent Circle should be drawn to the proportions of an average person, to accomodate everyone. | ||

| Line 1,440: | Line 1,440: | ||

Because what we have done was more for the contentment of those who would make a close study of our Theory, than it is something necessary for our Training. | Because what we have done was more for the contentment of those who would make a close study of our Theory, than it is something necessary for our Training. | ||

Other than that, we have tried to put everything in good order, so that each can easily distinguish between those things necessary for Practice, from those which are only for Theorists, as long as they read our writings attentively. | Other than that, we have tried to put everything in good order, so that each can easily distinguish between those things necessary for Practice, from those which are only for Theorists, as long as they read our writings attentively. | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | Pour venir à la Pratique de tout ce qui a eſté diſcouru, touchant la convenance du Cercle, & de l’Eſpee, avec le Corps de l’Homme; il eſt aiſé à un chaſcun d’avoir une Eſpee de ſa juſte meſure. | |

| − | |Pour venir à la Pratique de tout ce qui a eſté diſcouru, touchant la convenance du Cercle, & de l’Eſpee, avec le Corps de l’Homme; il eſt aiſé à un chaſcun d’avoir une Eſpee de ſa juſte meſure. | ||

Mais pour le Cercle, qu’on deſcrit une fois pour toutes, où il faut ſouventesfois faire des preuves avec perſonnes inegales de ſtature, aux quels il faudroit à chaſcun ſon propre Cercle; ou bien avec perſonnes egales, mais plus grandes, ou plus petites, que la ligne du Diametre, en ſorte que le Cercle ne ſeroit pas compaſſé à la proportion de leurs corps. | Mais pour le Cercle, qu’on deſcrit une fois pour toutes, où il faut ſouventesfois faire des preuves avec perſonnes inegales de ſtature, aux quels il faudroit à chaſcun ſon propre Cercle; ou bien avec perſonnes egales, mais plus grandes, ou plus petites, que la ligne du Diametre, en ſorte que le Cercle ne ſeroit pas compaſſé à la proportion de leurs corps. | ||

Pour obvier à ces inconvenients, il le faut tirer ſur la meſure d’une perſonne moyenne, afin qu’il ſoit capable d’eſtre accommodé à toutes. | Pour obvier à ces inconvenients, il le faut tirer ſur la meſure d’une perſonne moyenne, afin qu’il ſoit capable d’eſtre accommodé à toutes. | ||

| Line 1,464: | Line 1,463: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

! Transcription by <br/>[[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Transcription by <br/>[[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 1,959: | Line 1,958: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | First, do not attach the strap to the right and the hanger on the left side, as is the usual custom. Because if the strap is not supporting the sword, it will drop down in a loop across the knees. That is why it should attach to the middle of the torso, and from that, it follows that I attach the hanger more in back, so the sword is at the side, a little behind, supported by the hanger with help from the strap. The sword is firmly held against the side by the proper proportion of tension between the two. Secondly, it is apparent that the belt-strap should be shorter than is typical, because otherwise it cannot support the hanger, and will be too slack. Thirdly, it follows, that, in contrast, the hanger should be longer, because, by degrees that it becomes shorter, the belt-strap becomes looser, and would need to be shortened proportionally, which it cannot. It is also apparent that the Pendent should be a little shorter than the belt-strap, so that the sword hangs a little behind the hip, rather than at the side. If it were equal in length to the belt-strap, then the sword would hang equally between the two. As it is shorter, the sword is pulled comfortably around towards the back. Fifthly, it is also apparent why the belt-strap and hanger should have the exact lengths that I have given, neither longer, nor shorter, because there is no other length that puts the hilt at such a convenient height that the right hand can easily and quickly reach across and grab ahold of the handle while the left hand holds the scabbard so as to quickly draw the sword, which is the first move in self-defense. It is also the perfect height to rest one’s elbow on, as shown and explained by figure A in Plate I. Finally, for these reasons, one can easily see how my way of carrying the sword is not only the more convenient than the typical method, but it takes the prize for elegance and appearance. Which is why one comes to the same conclusion in almost everything, as the Father of Roman Eloquence said, ‘beauty consists of, and is found in, Utility.’ If something is not practical, it may be appear beautiful to an untutored onlooker, but the discerning gentleman will recognize the inferiority and imperfection that patinas the lustre of appearance. | |

| − | |First, do not attach the strap to the right and the hanger on the left side, as is the usual custom. Because if the strap is not supporting the sword, it will drop down in a loop across the knees. That is why it should attach to the middle of the torso, and from that, it follows that I attach the hanger more in back, so the sword is at the side, a little behind, supported by the hanger with help from the strap. The sword is firmly held against the side by the proper proportion of tension between the two. Secondly, it is apparent that the belt-strap should be shorter than is typical, because otherwise it cannot support the hanger, and will be too slack. Thirdly, it follows, that, in contrast, the hanger should be longer, because, by degrees that it becomes shorter, the belt-strap becomes looser, and would need to be shortened proportionally, which it cannot. It is also apparent that the Pendent should be a little shorter than the belt-strap, so that the sword hangs a little behind the hip, rather than at the side. If it were equal in length to the belt-strap, then the sword would hang equally between the two. As it is shorter, the sword is pulled comfortably around towards the back. Fifthly, it is also apparent why the belt-strap and hanger should have the exact lengths that I have given, neither longer, nor shorter, because there is no other length that puts the hilt at such a convenient height that the right hand can easily and quickly reach across and grab ahold of the handle while the left hand holds the scabbard so as to quickly draw the sword, which is the first move in self-defense. It is also the perfect height to rest one’s elbow on, as shown and explained by figure A in Plate I. Finally, for these reasons, one can easily see how my way of carrying the sword is not only the more convenient than the typical method, but it takes the prize for elegance and appearance. Which is why one comes to the same conclusion in almost everything, as the Father of Roman Eloquence said, ‘beauty consists of, and is found in, Utility.’ If something is not practical, it may be appear beautiful to an untutored onlooker, but the discerning gentleman will recognize the inferiority and imperfection that patinas the lustre of appearance. | + | | class="noline" | Premierement qu’on ne doit attacher le Ceinturon ſur le coſté droit, & le pendant ſur le coſté gauche, comme quelques uns on le couſtume. Car en ce faiſant, ſi le ceinturon ſouſtient aucunement l’eſpee, il aviendra qu’elle pendra par devant la perſonne de travers, en loy croiſant les genoux. Pour ceſte cauſe nous avons ordonné de l’attacher ſur le milieu du ventre, & le pendant de l’eſpee à l’advenant, autant plus en arriere; afin que l’eſpee revienne ſur le coſté de la perſonneun peu vers le derriere, & qu’elle ſoit ſouſtenue par le pendant à l’aide du Centuron; & affermie contre le corps par la juſte proportion de la diſtance de l’un à l’autre. Secondement il appert, que le Ceinturon doit eſtre plus court, qu’on ne le fait ordinairement; car ſans cela il ne peut ſoulager le pendant; d’autant qu’il demeure trop laſche. Pour le troiſieme s’enſuit, que le Pendant doit eſtre au contraire, plus long: car à meſure qu’on le prent plus court, le ceinturon s’en relaſche à l’advenant; de ſorte que’il faudroit auſsi raccoucir à meſme proportion le ceinturon: ce qui ne peut eſtre. Il en paroiſt auſſi ſemblablement, que le Pendant doit eſtre un peu plus court que’ n’eſt le ceinturon: pour ce qu’on ne porte pas l’eſpee juſtement au coſté, mais un peu en arriere devers le pendant de l’eſpee, qui doit eſtre le plus court, afin qu’il la tire d’avantage, car s’il eſtoit egal au ceinturon, l’eſpee pendroit au juſte entredeux. Maintenant qu’il eſt plus court, auſſi l’eſpee s’en accommode un peu d’avantage en arriere. Il en appert auſſi pour le cinquieme, pourquoy le Ceinturon & le Pendāt doivent avoir la juſte longueur, que nous leur avons aſſigné, non plus grande, & auſſi non plus petite: pour ce qu’il n’y a point d’autre meſure, que ceſte-cy ſeule, qui ſoit proportionnée à tenir la garde en ſa convenable hauteur, & à luy donner la ſituation la plus parfaite de toutes, pour mettre à meſme temps & à ſon aiſe la main droite à l’eſpee, & la gauche au fourreau, pour accomplir conſecutivement l’operation du deſgainement, qui eſt la premiere preparation pour ſe mettre en defenſe: voire auſſi pour repoſer le coude du bras gauche deſſus, en la maniere, & pour les cauſes, qui ſont expliquées au Tableau precedent ſur la figure A. En fin par ces raiſons il ſe voit, que noſtre façon de porter l’eſpee, n’eſt pas ſeulement plus commode, que la vulgaire; mais qu’elle en gaigne auſſi le prix au regard de la bienſeance, & de l’ornement de proportion; duquoy on voit quaſi arriver le ſemblable en toutes choſes, car ſelon ce qu’en a teſmoigné le grand Orateur & Pere de l’Eloquence Romaine, la beauté conſiſte, & ſe deſcouvre en l’Vſage meſme. Si quelque choſe eſloignée de l’utilité, ne laiſſe pas de ſembler aucunefois belle aux ignorants, toutesfois les gens de jugement y recognoiſſent touſiours une imperfećtion, qui obſeurcit le luſtre de leur apparence. |

| − | |||

| − | |Premierement qu’on ne doit attacher le Ceinturon ſur le coſté droit, & le pendant ſur le coſté gauche, comme quelques uns on le couſtume. Car en ce faiſant, ſi le ceinturon ſouſtient aucunement l’eſpee, il aviendra qu’elle pendra par devant la perſonne de travers, en loy croiſant les genoux. Pour ceſte cauſe nous avons ordonné de l’attacher ſur le milieu du ventre, & le pendant de l’eſpee à l’advenant, autant plus en arriere; afin que l’eſpee revienne ſur le coſté de la perſonneun peu vers le derriere, & qu’elle ſoit ſouſtenue par le pendant à l’aide du Centuron; & affermie contre le corps par la juſte proportion de la diſtance de l’un à l’autre. Secondement il appert, que le Ceinturon doit eſtre plus court, qu’on ne le fait ordinairement; car ſans cela il ne peut ſoulager le pendant; d’autant qu’il demeure trop laſche. Pour le troiſieme s’enſuit, que le Pendant doit eſtre au contraire, plus long: car à meſure qu’on le prent plus court, le ceinturon s’en relaſche à l’advenant; de ſorte que’il faudroit auſsi raccoucir à meſme proportion le ceinturon: ce qui ne peut eſtre. Il en paroiſt auſſi ſemblablement, que le Pendant doit eſtre un peu plus court que’ n’eſt le ceinturon: pour ce qu’on ne porte pas l’eſpee juſtement au coſté, mais un peu en arriere devers le pendant de l’eſpee, qui doit eſtre le plus court, afin qu’il la tire d’avantage, car s’il eſtoit egal au ceinturon, l’eſpee pendroit au juſte entredeux. Maintenant qu’il eſt plus court, auſſi l’eſpee s’en accommode un peu d’avantage en arriere. Il en appert auſſi pour le cinquieme, pourquoy le Ceinturon & le Pendāt doivent avoir la juſte longueur, que nous leur avons aſſigné, non plus grande, & auſſi non plus petite: pour ce qu’il n’y a point d’autre meſure, que ceſte-cy ſeule, qui ſoit proportionnée à tenir la garde en ſa convenable hauteur, & à luy donner la ſituation la plus parfaite de toutes, pour mettre à meſme temps & à ſon aiſe la main droite à l’eſpee, & la gauche au fourreau, pour accomplir conſecutivement l’operation du deſgainement, qui eſt la premiere preparation pour ſe mettre en defenſe: voire auſſi pour repoſer le coude du bras gauche deſſus, en la maniere, & pour les cauſes, qui ſont expliquées au Tableau precedent ſur la figure A. En fin par ces raiſons il ſe voit, que noſtre façon de porter l’eſpee, n’eſt pas ſeulement plus commode, que la vulgaire; mais qu’elle en gaigne auſſi le prix au regard de la bienſeance, & de l’ornement de proportion; duquoy on voit quaſi arriver le ſemblable en toutes choſes, car ſelon ce qu’en a teſmoigné le grand Orateur & Pere de l’Eloquence Romaine, la beauté conſiſte, & ſe deſcouvre en l’Vſage meſme. Si quelque choſe eſloignée de l’utilité, ne laiſſe pas de ſembler aucunefois belle aux ignorants, toutesfois les gens de jugement y recognoiſſent touſiours une imperfećtion, qui obſeurcit le luſtre de leur apparence. | ||

|} | |} | ||

{{master end}} | {{master end}} | ||

| Line 1,970: | Line 1,967: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 2,355: | Line 2,352: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

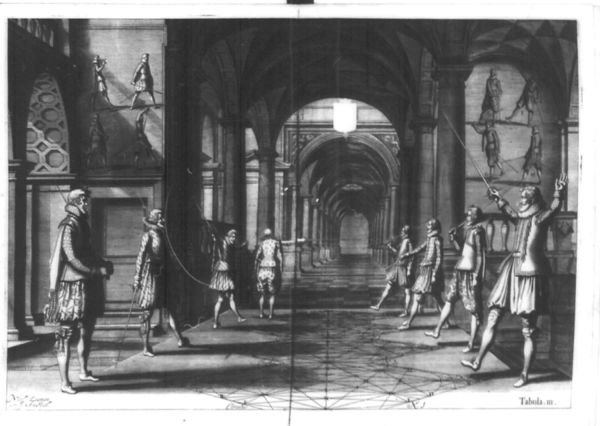

| − | + | | class="noline" | These are the actions he has done as shown in this Plate. The next will contain how he moves into range, advancing the right foot to the Circumference of the Circle, meanwhile swinging the tip of sword inversely from high to low, which he does with a twist of the wrist and a little motion of the arm and continuing on until he has put his blade underneath his opponent’s in parallel and in a direct line. But as these things are shown in the following Plate, I shall finish my explanation of the Third Plate and move on. | |

| − | |These are the actions he has done as shown in this Plate. The next will contain how he moves into range, advancing the right foot to the Circumference of the Circle, meanwhile swinging the tip of sword inversely from high to low, which he does with a twist of the wrist and a little motion of the arm and continuing on until he has put his blade underneath his opponent’s in parallel and in a direct line. But as these things are shown in the following Plate, I shall finish my explanation of the Third Plate and move on. | + | | class="noline" | Telles ſont les aćtions qu’il a faites en ce Tableau preſent; la ſuite contiendra cōment c’eſt qu’il entre en meſure, en avançant le pied droit juſqu’à la Circonference du Cercle, & tournant ce temps pendant la pointe de ſa lame circulairement à l’envers du haut en bas à ſon coſté; ce qu’il fait du poignet de la main avec quelque petite accommodation du bras, en continuant le meſme tour juſqu’à tant qu’il ait mis ſa lame deſſous l’eſpee contraire en ligne droite & parallele. Mais puis que ces choſes ſeront repreſentées au Tableau ſuivant, faiſons icy la fin du Troiſieme, & paſſons outre. |

| − | |||

| − | |Telles ſont les aćtions qu’il a faites en ce Tableau preſent; la ſuite contiendra cōment c’eſt qu’il entre en meſure, en avançant le pied droit juſqu’à la Circonference du Cercle, & tournant ce temps pendant la pointe de ſa lame circulairement à l’envers du haut en bas à ſon coſté; ce qu’il fait du poignet de la main avec quelque petite accommodation du bras, en continuant le meſme tour juſqu’à tant qu’il ait mis ſa lame deſſous l’eſpee contraire en ligne droite & parallele. Mais puis que ces choſes ſeront repreſentées au Tableau ſuivant, faiſons icy la fin du Troiſieme, & paſſons outre. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,367: | Line 2,362: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 2,700: | Line 2,695: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | In sum, this is the superiority of the Direct Line posture, presented at the distance of the First Instance. We could list even more reasons, if these were not self-evident enough, to persuade those who are open to the Truth. I truly believe that we have not unnecessarily repeated anything, but the usefulness of this subject shall serve as an excuse. Considering that such an important matter merits being treated with thoroughness. At this point, I shall leave the reader who can expect to shortly receive even more, just like a landlord who, allowing the rent to be uncollected one month, expects double the next. | |

| − | |In sum, this is the superiority of the Direct Line posture, presented at the distance of the First Instance. We could list even more reasons, if these were not self-evident enough, to persuade those who are open to the Truth. I truly believe that we have not unnecessarily repeated anything, but the usefulness of this subject shall serve as an excuse. Considering that such an important matter merits being treated with thoroughness. At this point, I shall leave the reader who can expect to shortly receive even more, just like a landlord who, allowing the rent to be uncollected one month, expects double the next. | + | | class="noline" | Voilà en ſomme, qu’elle eſt la perfećtion de la Droite ligne, à preſenter ſur la Premiere Inſtance. On en pourroit alleguer encore d’autres raiſons, ſi celles-cy n’eſtoyent aſſez evidentes pour perſuader la Verité à ceux, qui la veulent recevoir. Ie croy bien, que nous avons uſé aucunefois de quelques redites: mais l’utilité du ſujet en fera noſtre excuſe; conſiderant qu’une matiere de ſi grande importance ne meritoit, que d’eſtre traitée bien exaćtement; eſtant expedient d’y arreſter la contemplation du Lećteur, pour imiter en ceſt endroit les avaricieux, qui laiſſent longuement courrir leurs rentes, afin qu’ils les reçoivent par apres avec double uſure. |

| − | |||

| − | |Voilà en ſomme, qu’elle eſt la perfećtion de la Droite ligne, à preſenter ſur la Premiere Inſtance. On en pourroit alleguer encore d’autres raiſons, ſi celles-cy n’eſtoyent aſſez evidentes pour perſuader la Verité à ceux, qui la veulent recevoir. Ie croy bien, que nous avons uſé aucunefois de quelques redites: mais l’utilité du ſujet en fera noſtre excuſe; conſiderant qu’une matiere de ſi grande importance ne meritoit, que d’eſtre traitée bien exaćtement; eſtant expedient d’y arreſter la contemplation du Lećteur, pour imiter en ceſt endroit les avaricieux, qui laiſſent longuement courrir leurs rentes, afin qu’ils les reçoivent par apres avec double uſure. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,712: | Line 2,705: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 2,721: | Line 2,714: | ||

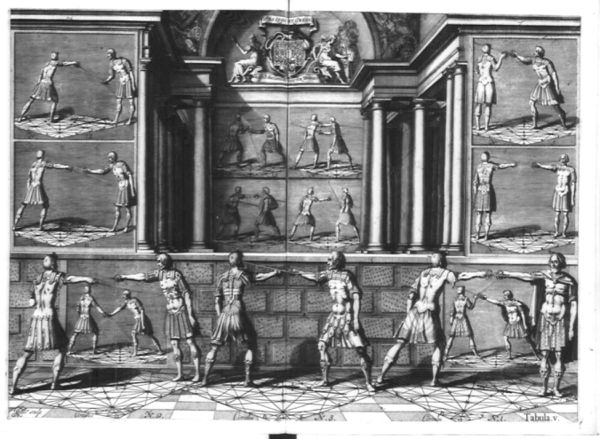

|Colspan="2"|[[file:Thibault L1 Tab 05.jpg|600px]] | |Colspan="2"|[[file:Thibault L1 Tab 05.jpg|600px]] | ||

| − | N.B., The coat of arms at the top belongs to | + | N.B., The coat of arms at the top belongs to [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Sigismund,_Elector_of_Brandenburg Johan Sigismund] (1572 – 1619), Elector of Brandenburg (1608 – 1619) of the House of Hohenzollern, Elector of Brandenburg from 1608 and Duke of Prussia, through his wife Anna, from 1618. |

| + | |||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; font-size: 16pt; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; font-size: 16pt; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| Line 3,102: | Line 3,096: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | To summarize, these are examples which show the great utility of our First Instance, and of the direct line posture when presented from there. One is fortified against all sorts of feints, and assured against all strikes, whether long and determined, or tentative and slow, high or low, made from a direct line or a bent line, on the inside or outside of the arm, to meet probes in one beat, and attacks in two beats, sometimes with the body erect, sometimes bent slightly forward or backwards, always striking with with small movements, which have more force than they seem, with more audacity and assurance than one thinks possible, quite the reverse of what we see in the usual style. If you were to tell me that there does not appear to be an easy way acquire sufficient skill to use this effectively, I would answer that nothing in life worth having comes without effort. In any case, I have made certain of the well-being of those who have not yet any ability, insofar as they put these precepts to the test. Because, just as gold purified in a furnace acquires greater luster, so with our exercises, that, when looked at closely, examined, attentively inspected, and practiced, with each repetition will appear more elegant and beautiful. When one conducts thorough research into these truths and their meaning, one will see they do not depend in any way on chance. The uncertainty of fortune does not appear anywhere. There is only the rules of science that dominate, in such a perfect way that any amateur who applies himself, will gain courage and confidence in his skill at arms, and the certainty and dexterity in their use which, when lacking, leave him weak and vulnerable. | |

| − | |To summarize, these are examples which show the great utility of our First Instance, and of the direct line posture when presented from there. One is fortified against all sorts of feints, and assured against all strikes, whether long and determined, or tentative and slow, high or low, made from a direct line or a bent line, on the inside or outside of the arm, to meet probes in one beat, and attacks in two beats, sometimes with the body erect, sometimes bent slightly forward or backwards, always striking with with small movements, which have more force than they seem, with more audacity and assurance than one thinks possible, quite the reverse of what we see in the usual style. If you were to tell me that there does not appear to be an easy way acquire sufficient skill to use this effectively, I would answer that nothing in life worth having comes without effort. In any case, I have made certain of the well-being of those who have not yet any ability, insofar as they put these precepts to the test. Because, just as gold purified in a furnace acquires greater luster, so with our exercises, that, when looked at closely, examined, attentively inspected, and practiced, with each repetition will appear more elegant and beautiful. When one conducts thorough research into these truths and their meaning, one will see they do not depend in any way on chance. The uncertainty of fortune does not appear anywhere. There is only the rules of science that dominate, in such a perfect way that any amateur who applies himself, will gain courage and confidence in his skill at arms, and the certainty and dexterity in their use which, when lacking, leave him weak and vulnerable. | + | | class="noline" | En fin, voilà les exemples, qui demonſtrent le grand uſage de noſtre Premiere Inſtance, & de la droite ligne preſentée en icelle: fortifiée contre toute ſorte de feintes, aſſeurée contre toutes bottes, tant longues & reſolues, que tardives & lentes, hautes, baſſes, tirées en ligne droite ou courbe, en dehors ou en dedans du bras, pour rencontrer otes en un temps & ores en deux, tantoſt avec le corps dreſſé, tantoſt un peu courbe en avant ou en arriere, en donnant touſiours le coup avec des petits mouvements, qui ont plus de force, que d’apparance, & en faiſant l’execution avec les plus hardis & aſſeurez, qu’il eſt poſsible, au rebours de ce que la Pratique vulgaire en monſtre. Si vous me dites, qu’il n’y a pas grande apparence de venir aiſement à ceſte perfećtion d’en monſtrer les effets; ſachez pour reſponſe, que tout ce qui eſt louable ne s’acquiert ordinairement, qu’à grand travail. toutesfois, je m’aſſeure encores pour le regard de ceux qui n’en auront encores nulle habitude, que d’autant plus qu’ils mettront les preceptes à l’eſpreuve, d’autant plus y trouveront ils de perfećtion. Car ainſi que l’or eſtant mis à la fournaiſe, en reçoit un plus grand luſtre, par l’approbation de ſa pureté; tout de meſme nos inſtrućtions, eſtants regardées de pres, examinées, contrerollées, pratiquées, & repetées en paroiſtront touſiours plus belles. Car quand on aura fait une digne recerche de leur Verité, & de leur importance, on verra que l’incertitude de la fortune n’y a nulle part, & que les ſeules regles de la ſcience y dominent en telle perfećtion, quel Amateur, qui s’en ſera rendu capable, empruntera meſme le courage & l’aſſeurance des armes, qui manque à la foibleſſe des ſes forces de la certitude & dexterité de leur uſage. |

| − | |||

| − | |En fin, voilà les exemples, qui demonſtrent le grand uſage de noſtre Premiere Inſtance, & de la droite ligne preſentée en icelle: fortifiée contre toute ſorte de feintes, aſſeurée contre toutes bottes, tant longues & reſolues, que tardives & lentes, hautes, baſſes, tirées en ligne droite ou courbe, en dehors ou en dedans du bras, pour rencontrer otes en un temps & ores en deux, tantoſt avec le corps dreſſé, tantoſt un peu courbe en avant ou en arriere, en donnant touſiours le coup avec des petits mouvements, qui ont plus de force, que d’apparance, & en faiſant l’execution avec les plus hardis & aſſeurez, qu’il eſt poſsible, au rebours de ce que la Pratique vulgaire en monſtre. Si vous me dites, qu’il n’y a pas grande apparence de venir aiſement à ceſte perfećtion d’en monſtrer les effets; ſachez pour reſponſe, que tout ce qui eſt louable ne s’acquiert ordinairement, qu’à grand travail. toutesfois, je m’aſſeure encores pour le regard de ceux qui n’en auront encores nulle habitude, que d’autant plus qu’ils mettront les preceptes à l’eſpreuve, d’autant plus y trouveront ils de perfećtion. Car ainſi que l’or eſtant mis à la fournaiſe, en reçoit un plus grand luſtre, par l’approbation de ſa pureté; tout de meſme nos inſtrućtions, eſtants regardées de pres, examinées, contrerollées, pratiquées, & repetées en paroiſtront touſiours plus belles. Car quand on aura fait une digne recerche de leur Verité, & de leur importance, on verra que l’incertitude de la fortune n’y a nulle part, & que les ſeules regles de la ſcience y dominent en telle perfećtion, quel Amateur, qui s’en ſera rendu capable, empruntera meſme le courage & l’aſſeurance des armes, qui manque à la foibleſſe des ſes forces de la certitude & dexterité de leur uſage. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 3,114: | Line 3,106: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 3,426: | Line 3,418: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

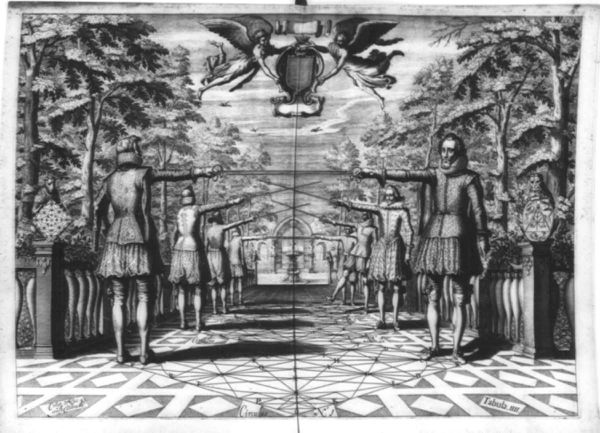

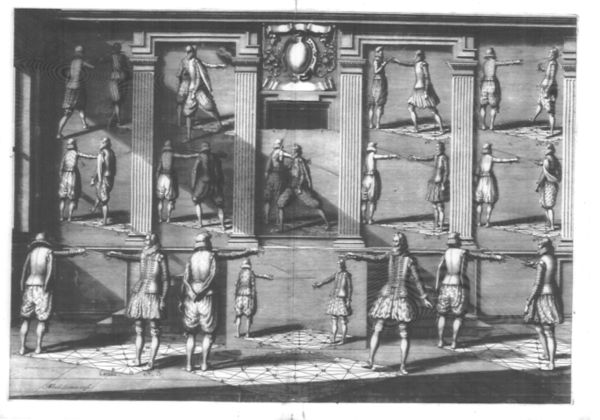

| − | + | | class="noline" | It is apparent from these examples that before one can hit the person who is holding the Direct Line posture, one must first overcome the sword. Because the large distance at the First Instance is advantageous and good for the defender, as much, in contrast, as it is difficult and inconvenient for the attacker. In fact, if you paid close attention to the demonstrations in the previous Plate V, all of Zachary’s thrusts were made from the First Instance, all of their counters were made by Alexander from the Second. As much as he never stayed in place without moving, nonetheless his hits were only begun at the instant when his enemy had closed in to the Second Instance. If someone is out of range, he is also out of danger; when at long range, he is likewise out of danger from smaller and more subtle moves. Thus is follows that, when the enemy is standing in the Direct Line posture, that one must move in closer to put him in danger, but confidently. Good foot, good eye. Believe that neither the speed of the body, nor the quickness of the arm, are nothing compared to the benefit of a good approach. Thus all the practicality of our Training is that we are always moving towards the enemy to come into the range that is most convenient and proper to the execution of our attacks. That is, if he does not bring himself into range and save us the trouble. This is what we wanted to present here, in Plate VI. More specific observations and confidence in how to proceed, shall be explained hereafter, each in its proper place. | |

| − | |It is apparent from these examples that before one can hit the person who is holding the Direct Line posture, one must first overcome the sword. Because the large distance at the First Instance is advantageous and good for the defender, as much, in contrast, as it is difficult and inconvenient for the attacker. In fact, if you paid close attention to the demonstrations in the previous Plate V, all of Zachary’s thrusts were made from the First Instance, all of their counters were made by Alexander from the Second. As much as he never stayed in place without moving, nonetheless his hits were only begun at the instant when his enemy had closed in to the Second Instance. If someone is out of range, he is also out of danger; when at long range, he is likewise out of danger from smaller and more subtle moves. Thus is follows that, when the enemy is standing in the Direct Line posture, that one must move in closer to put him in danger, but confidently. Good foot, good eye. Believe that neither the speed of the body, nor the quickness of the arm, are nothing compared to the benefit of a good approach. Thus all the practicality of our Training is that we are always moving towards the enemy to come into the range that is most convenient and proper to the execution of our attacks. That is, if he does not bring himself into range and save us the trouble. This is what we wanted to present here, in Plate VI. More specific observations and confidence in how to proceed, shall be explained hereafter, each in its proper place. | + | | class="noline" | Il appert par ces exemples, qu’il faut neceſſairement venir à l’eſpee, premier que d’attenter ſur la perſonne, qui ſe tient en ceſte poſture de la Droite ligne. Car la meſure large de la Premiere Inſtance, luy eſt avantageuſe & propre pour les defenſes, autant qu’elle eſt au contraire incommode & dangereuſe pour celuy qui la veut aſſaillir. Et de fait ſi vous avez prins bonne garde aux demonſtrations de la Table V. precedente, toutes les eſtocades de Zacharie, qu’il y eſt repreſenté d’avoir tirées de la Premiere Inſtance, elles ont eſté rencontrees par Alexandre à la Seconde. Car encores qu’il ſoit demeuré aucunesfois ſans bouger de ſa place, toutesfois les atteintes, qu’il a données, n’ont eſté commencées, ſinon à l’inſtant que l’Ennemi s’eſt avancé juſqu’à ceſte Seconde Inſtance. Car ſi celuy qui eſt hors de meſure, eſt auſſi hors de danger, auſſi qui eſt en meſure large, eſt hors du danger des plus petits & plus ſubtils mouvements. S’enſuit donc, quand l’Ennemi ſe tient en la Droite ligne, qu’il le faut aborder plus pres, pour le mettre en danger; mais avec aſſeurance, Bon pied, bon œil. Et croyez hardiment, que ny la viſteſſe du corps, ny la promptitude du bras, ne ſont rien au prix d’une bonne approche. Dont toute la Pratique de ceſtuy noſtre Exercice ſera telle, qu’on ira touſiours ſerrant l’Ennemy, juſqu’à venir à la meſure, qui ſoit convenable & juſte aux executions, qui ſe preſentent à faire; ſi ce n’eſt que luy meſme nous vienne au devant, pour nous relever de la peine. Voilà ce que nous avons voulu repreſenter en general en ce Tableau VI. Les obſervations plus particulieres, & l’aſſeurance, comment il y faut proceder, ſeront declarées cy apres, chaſcune en ſon lieu. |

| − | |||

| − | |Il appert par ces exemples, qu’il faut neceſſairement venir à l’eſpee, premier que d’attenter ſur la perſonne, qui ſe tient en ceſte poſture de la Droite ligne. Car la meſure large de la Premiere Inſtance, luy eſt avantageuſe & propre pour les defenſes, autant qu’elle eſt au contraire incommode & dangereuſe pour celuy qui la veut aſſaillir. Et de fait ſi vous avez prins bonne garde aux demonſtrations de la Table V. precedente, toutes les eſtocades de Zacharie, qu’il y eſt repreſenté d’avoir tirées de la Premiere Inſtance, elles ont eſté rencontrees par Alexandre à la Seconde. Car encores qu’il ſoit demeuré aucunesfois ſans bouger de ſa place, toutesfois les atteintes, qu’il a données, n’ont eſté commencées, ſinon à l’inſtant que l’Ennemi s’eſt avancé juſqu’à ceſte Seconde Inſtance. Car ſi celuy qui eſt hors de meſure, eſt auſſi hors de danger, auſſi qui eſt en meſure large, eſt hors du danger des plus petits & plus ſubtils mouvements. S’enſuit donc, quand l’Ennemi ſe tient en la Droite ligne, qu’il le faut aborder plus pres, pour le mettre en danger; mais avec aſſeurance, Bon pied, bon œil. Et croyez hardiment, que ny la viſteſſe du corps, ny la promptitude du bras, ne ſont rien au prix d’une bonne approche. Dont toute la Pratique de ceſtuy noſtre Exercice ſera telle, qu’on ira touſiours ſerrant l’Ennemy, juſqu’à venir à la meſure, qui ſoit convenable & juſte aux executions, qui ſe preſentent à faire; ſi ce n’eſt que luy meſme nous vienne au devant, pour nous relever de la peine. Voilà ce que nous avons voulu repreſenter en general en ce Tableau VI. Les obſervations plus particulieres, & l’aſſeurance, comment il y faut proceder, ſeront declarées cy apres, chaſcune en ſon lieu. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 3,438: | Line 3,428: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 3,448: | Line 3,438: | ||

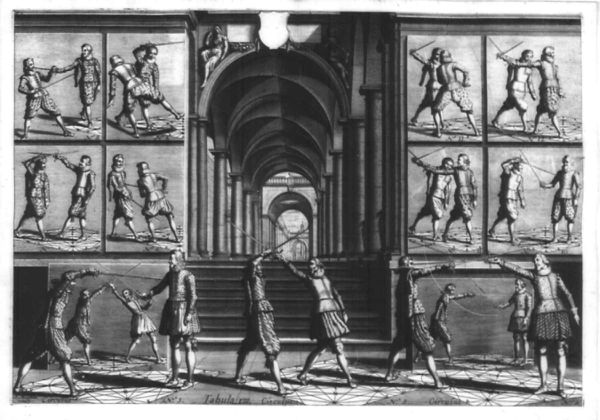

| − | N.B., the coat of arms at the top belongs to George William (1595 – 1640) of the House of Hohenzollern, Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia from 1619. | + | N.B., the coat of arms at the top belongs to [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_William,_Elector_of_Brandenburg George William] (1595 – 1640) of the House of Hohenzollern, Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia from 1619. |

| + | |||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; font-size: 16pt; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; font-size: 16pt; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| Line 3,946: | Line 3,937: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

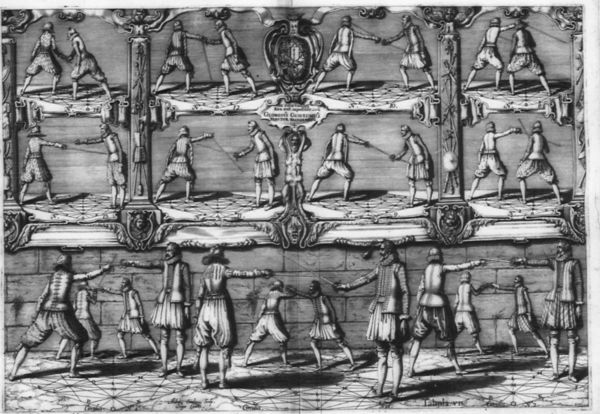

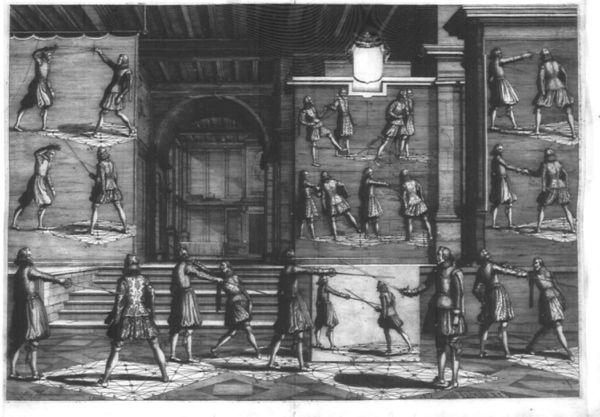

| − | + | | class="noline" | The principle to which every student must aspire in performing the actions in the Plate, is to have exact timing. This is one of the most important points of the entire system, and without this, nothing can be performed either gracefully or surely. For if Hypocrites, that Prince of Doctors, dared pronounce only with care on matters of medicine, which was difficult to observe and diagnose, even when the sypmtoms endured for days, or, at the least, hours, we have even more reason to say, how fast and difficult is the Practice of Arms, wherein we have often a moment of time, and often are presented with but an instant to decide, which is a point of time, indivisible, and without any duration. As such, there are times wherein we can find an opportunity, but few opportunities wherein we find much time. Which is why those who strive to reach this high goal to comprehend correct feel and timing, I shall warn them now, that they must not assume this is an easy thing and they must not be bored with spending a long time practising these exercises presented in this Plate VII. For beyond the confidence that they will provide in the prefection of the Theory and Practice of Arms, they may also be, in and of themselves alone, enough to become competent to enter into a fight against the greatest and toughest fighters they may find, as long as they do not play at learning to feel the sense of contact. For these others are not accustomed to having their swords crossed and in contact and even when they are closely embroiled, they always do their best to detach before they can be subjugated. Thus they do not usually present any other action than those which you see represented in this Plate, so that the time spent on these exercises could not be better used. | |

| − | |The principle to which every student must aspire in performing the actions in the Plate, is to have exact timing. This is one of the most important points of the entire system, and without this, nothing can be performed either gracefully or surely. For if Hypocrites, that Prince of Doctors, dared pronounce only with care on matters of medicine, which was difficult to observe and diagnose, even when the sypmtoms endured for days, or, at the least, hours, we have even more reason to say, how fast and difficult is the Practice of Arms, wherein we have often a moment of time, and often are presented with but an instant to decide, which is a point of time, indivisible, and without any duration. As such, there are times wherein we can find an opportunity, but few opportunities wherein we find much time. Which is why those who strive to reach this high goal to comprehend correct feel and timing, I shall warn them now, that they must not assume this is an easy thing and they must not be bored with spending a long time practising these exercises presented in this Plate VII. For beyond the confidence that they will provide in the prefection of the Theory and Practice of Arms, they may also be, in and of themselves alone, enough to become competent to enter into a fight against the greatest and toughest fighters they may find, as long as they do not play at learning to feel the sense of contact. For these others are not accustomed to having their swords crossed and in contact and even when they are closely embroiled, they always do their best to detach before they can be subjugated. Thus they do not usually present any other action than those which you see represented in this Plate, so that the time spent on these exercises could not be better used. | + | | class="noline" | Le principal que le Diſciple doibt pretendre en la Pratique de ce Tableau preſent, c’eſt de prendre exaćtement le temps: qui eſt l’un des plus importants points de tout l’Exercice, & ſans lequel il n’y a rien qui puiſſe eſtre pratiqué ny avec bonne grace ny avec aſſurance. Car ſi Hippocras le Prince des Medecins a oſé prononcer que l’occaſion en medicine eſt difficile à obſerver & à prendre, laquelle y dure cependant des jours ou à tout le moins des heures entieres, à plus forte raiſon pourrons nous dire, qu’elle eſt tresſoudaine & difficile en l’Exercice des Armes, où elle ne dure ſouvent qu’un moment de temps, & ſouvent qu’elle ne s’y preſente qu’en un ſimple Inſtant, qui eſt un poinćt de temps indiviſible & ſans duree quelconque. En ſorte qu’il y a temps auquel on trouve de l’occaſion, mais bien peu d’occaſions où il ſe trouve du temps. Parquoy ceux qui taſcheront de parvenir à ce haut but de cognoiſtre & prendre juſtement les temps, je les avertis, qu’il ne l’eſtiment pas pour choſe facile, & qu’il ne leur ennuye pas de mettre un long Exercice en l’uſage des preſentes leçons de ce Tableau VII. car outre l’aſſeurance qu’elles leur donneront en la parfaite Theorie & Pratique des Armes, auſsi pourront elles eſtre quaſi ſeules tenues pour ſuffiſantes dentrer en la lice avec les plus grands & hardis tireurs d’Armes qu’ils puiſſent trouver, moyennant qu’ils ne jouent pas ſur le ſentiment. Car puis qu’ils ne ſont pas accouſtumez d’avoir les eſpees accouplées, & meſmes qu’ils s’en trouvent incontinent embrouillez, ils font touſiours leur devoir de les deſtacher avant qu’on les puiſſe aſſujettir. dont il ne ſe preſente ordinairement quaſi nulle autre operation que celles que vous voyez repreſentées en ce Tableau. de façon que le temps qu’on y mettra, ne pourra eſtre que tresbien employé. |

| − | |||

| − | |Le principal que le Diſciple doibt pretendre en la Pratique de ce Tableau preſent, c’eſt de prendre exaćtement le temps: qui eſt l’un des plus importants points de tout l’Exercice, & ſans lequel il n’y a rien qui puiſſe eſtre pratiqué ny avec bonne grace ny avec aſſurance. Car ſi Hippocras le Prince des Medecins a oſé prononcer que l’occaſion en medicine eſt difficile à obſerver & à prendre, laquelle y dure cependant des jours ou à tout le moins des heures entieres, à plus forte raiſon pourrons nous dire, qu’elle eſt tresſoudaine & difficile en l’Exercice des Armes, où elle ne dure ſouvent qu’un moment de temps, & ſouvent qu’elle ne s’y preſente qu’en un ſimple Inſtant, qui eſt un poinćt de temps indiviſible & ſans duree quelconque. En ſorte qu’il y a temps auquel on trouve de l’occaſion, mais bien peu d’occaſions où il ſe trouve du temps. Parquoy ceux qui taſcheront de parvenir à ce haut but de cognoiſtre & prendre juſtement les temps, je les avertis, qu’il ne l’eſtiment pas pour choſe facile, & qu’il ne leur ennuye pas de mettre un long Exercice en l’uſage des preſentes leçons de ce Tableau VII. car outre l’aſſeurance qu’elles leur donneront en la parfaite Theorie & Pratique des Armes, auſsi pourront elles eſtre quaſi ſeules tenues pour ſuffiſantes dentrer en la lice avec les plus grands & hardis tireurs d’Armes qu’ils puiſſent trouver, moyennant qu’ils ne jouent pas ſur le ſentiment. Car puis qu’ils ne ſont pas accouſtumez d’avoir les eſpees accouplées, & meſmes qu’ils s’en trouvent incontinent embrouillez, ils font touſiours leur devoir de les deſtacher avant qu’on les puiſſe aſſujettir. dont il ne ſe preſente ordinairement quaſi nulle autre operation que celles que vous voyez repreſentées en ce Tableau. de façon que le temps qu’on y mettra, ne pourra eſtre que tresbien employé. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 3,958: | Line 3,947: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 4,247: | Line 4,236: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | Here then, in these two Plates VII & VIII, we have presented the actions which will typically be used against those whose style of fighting does not involve swords in contact. As such, its usefulness is self-evident. But speaking especially about Plate VIII, I believe I should not be taken to task for the most part for these demonstrations, with these reversals of the arm, raising it up to, or even above, head-height, and making this jump from about the Third Instance to the adversary’s side, and making these spinning moves, both high and low, which appear to be strange and extreme, and, what is worst of all, to be disadvantageous to someone attempting them. To which I must respond that mistakes made while trying to follow these instructions should not be taken as a weakness of an otherwise powerful art. For, insofar as untrained students may not be able to successfully execute these moves, this does not mean the principles are not correct. Which is why, if any would criticize this system, they must show that there is some fault in the action being displayed, such as taking too long to set up, or being too awkward to perform the move as shown. To say these are extremely difficult moves means nothing if they cannot show an easier one instead, which would be appropriate in the same situations. Because everything we do is forced on us in response to our opponents moves. Because, in any case, the law of performing movements in a natural way must be held inviolable, you understand that there is nothing more compelling than necessity, which force drives all laws to be as stable as they can be. This is a general answer, which must suffice to respond to criticisms that these movements shown here are not natural, which entirely wrong. These may be difficult to put into practice at first, nevertheless, with a little practice, they become very easy to do, so that when and where they are needed, they can be done quite gracefully, and unbelievably quickly, and very successfully, not done by chance, but through skillful application of this art, grounded in rational science. These examples should not be taken as in any way unnatural, because Nature herself not only advocates these methods, but teaches us they are the answer when we are pressed to the point of being able to do nothing else, in the same way that Nature instructs a man who has fallen into the water to swim. I will say that this art does have some apparently strange moves, and is, at first, quite difficult to learn, but after some training, one will find oneself so capable, that there is not one person in the whole world who would not admit that this art is entirely in accordance with natural principles. | |

| − | |Here then, in these two Plates VII & VIII, we have presented the actions which will typically be used against those whose style of fighting does not involve swords in contact. As such, its usefulness is self-evident. But speaking especially about Plate VIII, I believe I should not be taken to task for the most part for these demonstrations, with these reversals of the arm, raising it up to, or even above, head-height, and making this jump from about the Third Instance to the adversary’s side, and making these spinning moves, both high and low, which appear to be strange and extreme, and, what is worst of all, to be disadvantageous to someone attempting them. To which I must respond that mistakes made while trying to follow these instructions should not be taken as a weakness of an otherwise powerful art. For, insofar as untrained students may not be able to successfully execute these moves, this does not mean the principles are not correct. Which is why, if any would criticize this system, they must show that there is some fault in the action being displayed, such as taking too long to set up, or being too awkward to perform the move as shown. To say these are extremely difficult moves means nothing if they cannot show an easier one instead, which would be appropriate in the same situations. Because everything we do is forced on us in response to our opponents moves. Because, in any case, the law of performing movements in a natural way must be held inviolable, you understand that there is nothing more compelling than necessity, which force drives all laws to be as stable as they can be. This is a general answer, which must suffice to respond to criticisms that these movements shown here are not natural, which entirely wrong. These may be difficult to put into practice at first, nevertheless, with a little practice, they become very easy to do, so that when and where they are needed, they can be done quite gracefully, and unbelievably quickly, and very successfully, not done by chance, but through skillful application of this art, grounded in rational science. These examples should not be taken as in any way unnatural, because Nature herself not only advocates these methods, but teaches us they are the answer when we are pressed to the point of being able to do nothing else, in the same way that Nature instructs a man who has fallen into the water to swim. I will say that this art does have some apparently strange moves, and is, at first, quite difficult to learn, but after some training, one will find oneself so capable, that there is not one person in the whole world who would not admit that this art is entirely in accordance with natural principles. | + | | class="noline" | Or voilà donc en ces deux Tableaux VII. & VIII. les operations qui ſe preſentent ordinairement à faire contre ceux qui ſont accouſtumez à tirer des armes ſans l’uſage du ſentiment. En ſorte que l’utilité en eſt evidente d’elle meſme. Mais touchant ſpecialement le VIII. je croy qu’il ne faudra pas d’eſtre reprins en la plus part de ſes demonſtrations en ces renuerſemens du bras à porter en haut à l’egal de la teſte ou encores plus, en ce ſaut à faire depuis environ la Troiſeme Inſtance juſques à coſté de l’adverſaire, & en ces voltes du corps tant hautes que baſſes, qui ſembleront à pluſieures eſtre des mouvements eſtranges, & extremes, & qui eſt le pire de tout, deſavantageus pour celuy qui les voudroit mettre en pratique. Auxquels il faudra reſpondre, que les fautes commiſes a l’encontre des regles ne doivent prejudicier à la certitude de l’art meſme. Car encores que le diſciple malverſé n’en puiſſe venir à bout, toutesfois les preceptes n’en laiſſent pas d’eſtre juſtes. Parquoy s’ils les veulent reprendre il faut qu’il nous demonſtrent, qu’il y a de la faute en la demonſtration meſme, comme n’ayant pas le temps ou la preparation ou la commodité requiſe pour mettre en œuvre ce qu’elle monſtre. Car de dire que ce ſont des mouvements extremes, cela n’importe ſi ce n’eſt qu’ils nous en monſtrent des autres plus faciles, qui ſoyent neantmoins convenables en ces meſmes occaſions. Car tout ce que nous faiſons l’adverſaire nous y force: & partant combien que la loy de ſuivre les mouvements naturels doive eſtre inviolable, toutsfois il faut entendre que la neceſsité n’en a nulle, & qu’elle enfonce toutes loix quelques ſtables qu’elles puiſſent eſtre. Ce que nous alleguons pour une reſponce generalle, qui pourroit eſtre tenue pour ſuffiſante, encores que les mouvements icy repreſentez fuſſent contre la nature, ce qui eſt toutesfois autrement. Car encores qu’il ſoyent difficiles à pratiquer du commencement, ce neantmoins ils nous ſont rendus par l’excercice tres faciles, en ſorte qu’en lieu & temps on s’en ſert avec tres-bonne graçe, voire avec une viſteſſe incroyable, & avec un heureux ſuccés procedant non par hazard mais de la ſevreté de l’art, fondé en raiſon naturelle. Ces exemples ne doivent donc pas eſtre tenues pour choſes contre Nature, puis que c’eſt la nature meſme qui non ſeulement les avoüe, mais meſme les enſeigne, quand elle eſt reduite au point de ne pouvoir autrement; tout ainſi qu’elle monſtre à l’homme eſtant tombe en l’eau l’art de la nage; jaçoit que ledit art conſiſte en des mouvements fort eſtranges, & du commencement fort difficiles à apprendre: deſquels il ſe rend toutesfoit par l’exercice ſi capable, qu’il n’y a perſonne au Monde, qui ne confeſſe que ledit art ne ſoit du tout accordant à la Nature. |

| − | |||

| − | |Or voilà donc en ces deux Tableaux VII. & VIII. les operations qui ſe preſentent ordinairement à faire contre ceux qui ſont accouſtumez à tirer des armes ſans l’uſage du ſentiment. En ſorte que l’utilité en eſt evidente d’elle meſme. Mais touchant ſpecialement le VIII. je croy qu’il ne faudra pas d’eſtre reprins en la plus part de ſes demonſtrations en ces renuerſemens du bras à porter en haut à l’egal de la teſte ou encores plus, en ce ſaut à faire depuis environ la Troiſeme Inſtance juſques à coſté de l’adverſaire, & en ces voltes du corps tant hautes que baſſes, qui ſembleront à pluſieures eſtre des mouvements eſtranges, & extremes, & qui eſt le pire de tout, deſavantageus pour celuy qui les voudroit mettre en pratique. Auxquels il faudra reſpondre, que les fautes commiſes a l’encontre des regles ne doivent prejudicier à la certitude de l’art meſme. Car encores que le diſciple malverſé n’en puiſſe venir à bout, toutesfois les preceptes n’en laiſſent pas d’eſtre juſtes. Parquoy s’ils les veulent reprendre il faut qu’il nous demonſtrent, qu’il y a de la faute en la demonſtration meſme, comme n’ayant pas le temps ou la preparation ou la commodité requiſe pour mettre en œuvre ce qu’elle monſtre. Car de dire que ce ſont des mouvements extremes, cela n’importe ſi ce n’eſt qu’ils nous en monſtrent des autres plus faciles, qui ſoyent neantmoins convenables en ces meſmes occaſions. Car tout ce que nous faiſons l’adverſaire nous y force: & partant combien que la loy de ſuivre les mouvements naturels doive eſtre inviolable, toutsfois il faut entendre que la neceſsité n’en a nulle, & qu’elle enfonce toutes loix quelques ſtables qu’elles puiſſent eſtre. Ce que nous alleguons pour une reſponce generalle, qui pourroit eſtre tenue pour ſuffiſante, encores que les mouvements icy repreſentez fuſſent contre la nature, ce qui eſt toutesfois autrement. Car encores qu’il ſoyent difficiles à pratiquer du commencement, ce neantmoins ils nous ſont rendus par l’excercice tres faciles, en ſorte qu’en lieu & temps on s’en ſert avec tres-bonne graçe, voire avec une viſteſſe incroyable, & avec un heureux ſuccés procedant non par hazard mais de la ſevreté de l’art, fondé en raiſon naturelle. Ces exemples ne doivent donc pas eſtre tenues pour choſes contre Nature, puis que c’eſt la nature meſme qui non ſeulement les avoüe, mais meſme les enſeigne, quand elle eſt reduite au point de ne pouvoir autrement; tout ainſi qu’elle monſtre à l’homme eſtant tombe en l’eau l’art de la nage; jaçoit que ledit art conſiſte en des mouvements fort eſtranges, & du commencement fort difficiles à apprendre: deſquels il ſe rend toutesfoit par l’exercice ſi capable, qu’il n’y a perſonne au Monde, qui ne confeſſe que ledit art ne ſoit du tout accordant à la Nature. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 4,259: | Line 4,246: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 4,268: | Line 4,255: | ||

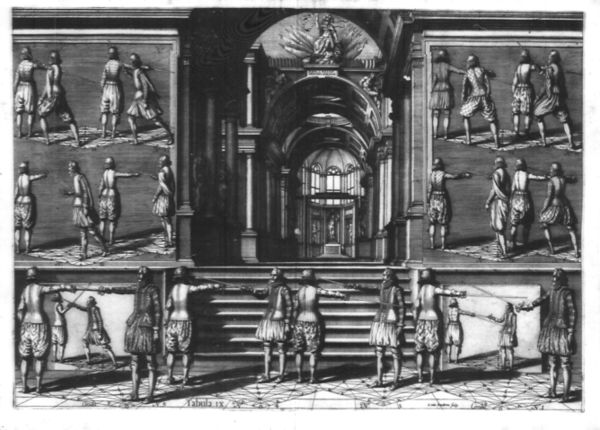

|Colspan="2"|[[file:Thibault L1 Tab 09.jpg|600px]] | |Colspan="2"|[[file:Thibault L1 Tab 09.jpg|600px]] | ||

| − | N.B., the coat of arms at the top belongs to Maurice of Nassau | + | N.B., the coat of arms at the top belongs to [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maurice,_Prince_of_Orange Maurice] of Nassau (1567 - 1625), who became Prince of Orange in 1618. |

|- style="font-family: times, serif; font-size: 16pt; vertical-align:top;font-variant: small-caps" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; font-size: 16pt; vertical-align:top;font-variant: small-caps" | ||

| Line 4,841: | Line 4,828: | ||

|Que s’il advenoit que Zacharie pare l’eſtocade qui luy eſt dreſſé devers le viſage en hauſſant ſimplement les eſpees, avec moins de Poids que nous ne venōs de ſepcifier, & qu’il ſe contentaſt d’y appliquer le Gaillard, Plus-gaillard, ou Tres-Gaillard, à l’exemple des Cercles 7. 8. & 9. dont il advendroit que ſa lame ne s’en fuyeroit pas aſſez viſtement; alors il la faudroit derechef deſgraduer & remettre en ſubjećtion; comme il a eſté fait & repreſenté au Cercle 10. ſur les meſmes Poids. | |Que s’il advenoit que Zacharie pare l’eſtocade qui luy eſt dreſſé devers le viſage en hauſſant ſimplement les eſpees, avec moins de Poids que nous ne venōs de ſepcifier, & qu’il ſe contentaſt d’y appliquer le Gaillard, Plus-gaillard, ou Tres-Gaillard, à l’exemple des Cercles 7. 8. & 9. dont il advendroit que ſa lame ne s’en fuyeroit pas aſſez viſtement; alors il la faudroit derechef deſgraduer & remettre en ſubjećtion; comme il a eſté fait & repreſenté au Cercle 10. ſur les meſmes Poids. | ||

| − | |- | + | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" |

| − | | | + | || |

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | All of these examples serve to demonstrate the great importance of the sense of Feel, which is so frequently held in such little esteem by Masters of this profession. But seeing how the truth is so self-evident, they are, despite their wishes, constrained to know something about how forces act on the blade. But as soon as one attacks their blade, they feel hindered, and try by all means to deliver themselves from these straits, either by withdrawing, or by circular disengagements, or by feints, or grosser actions which are slow and take up time that they might have used to better advantage. If only they were not so enamoured of nurturing their ignorance, rather than learning to do better. At the least, as they feel hindered by the coupling of swords, they ought to consider that if they are themselves inconvenienced, that their adversary is no more free of this hindrance than they, and while some hindrances are greater than others, all these can be made more effective by following the same basic principles. And each of these hindrances can be remedied with it’s own counter move. These Masters ought to be advised they can lessen their own sense of hindrance, and increase that of their adversaries, merely by means of the sense and feel of the blade in their hand, without immediately losing their courage to desperation, for which there is no remedy except to escape as quickly as possible. This is completely the reverse of how to respond. Because experience not only demonstrates to us the importance of a sense of feeling for assessing and knowing things, but, moreso, it is a common language we can all learn, that there is nothing more sure and certain than the touch of the hand. We see that the blind know with only their sense of touch the different values of coins, and how to find their way along the streets to their intended destination. And following their example, when we find ourselves in the obscurity of darkness, we do the same. And because, in the Exercise of Arms, it is necessary to be able to discern the power or weakness of your opponent as he moves. How else do they think one could possibly understand, if not by a sense of feel through the crossing of swords and the heaviness or lightness of that touch, which is the real goal and purpose of the use of this sense. As such, it is necessary to ignore these men or to listen to them while keeping this fact in mind. By what other means would they have us know when our opponent begins to act against us, so that we can counter him, if not by the sense of feel that comes from crossing swords, where we can detect when he is about to begin because the force of his blade against our own becomes lighter? The sense of feel tells us in half the time it takes for us to see what is happening. Finally, how else would they have it, that we can work with confidence against someone, if we do not have a sense of feel by which we can know with how much force, and on which side, our opponent is attacking? Considering these points, it is easy to see that those who hold as detrimental such a useful ability are holding to false doctrines. For as soon as we have crossed swords, we can approach our opponent with confidence, because we are certain to know in good time, all the designs he would undertake against. Designs which he cannot even begin to execute, but we are already prepared against him. This is such a notable advantage, one which has been in use in the Exercise of Arms for so long, yet without these masters having been able to see it. This is a skill so obvious, so important, and so necessary, that those who have not completely learned it have no better ability than one who has never touched a weapon in his life. And through ignorance of this, they hold the belief that approaching an opponent is so dangerous that they must make use of main-gauche, or two swords, as if the sword was not entirely sufficient in and of itself for both the defence of the of the holder and causing harm to an opponent. | |

| − | |All of these examples serve to demonstrate the great importance of the sense of Feel, which is so frequently held in such little esteem by Masters of this profession. But seeing how the truth is so self-evident, they are, despite their wishes, constrained to know something about how forces act on the blade. But as soon as one attacks their blade, they feel hindered, and try by all means to deliver themselves from these straits, either by withdrawing, or by circular disengagements, or by feints, or grosser actions which are slow and take up time that they might have used to better advantage. If only they were not so enamoured of nurturing their ignorance, rather than learning to do better. At the least, as they feel hindered by the coupling of swords, they ought to consider that if they are themselves inconvenienced, that their adversary is no more free of this hindrance than they, and while some hindrances are greater than others, all these can be made more effective by following the same basic principles. And each of these hindrances can be remedied with it’s own counter move. These Masters ought to be advised they can lessen their own sense of hindrance, and increase that of their adversaries, merely by means of the sense and feel of the blade in their hand, without immediately losing their courage to desperation, for which there is no remedy except to escape as quickly as possible. This is completely the reverse of how to respond. Because experience not only demonstrates to us the importance of a sense of feeling for assessing and knowing things, but, moreso, it is a common language we can all learn, that there is nothing more sure and certain than the touch of the hand. We see that the blind know with only their sense of touch the different values of coins, and how to find their way along the streets to their intended destination. And following their example, when we find ourselves in the obscurity of darkness, we do the same. And because, in the Exercise of Arms, it is necessary to be able to discern the power or weakness of your opponent as he moves. How else do they think one could possibly understand, if not by a sense of feel through the crossing of swords and the heaviness or lightness of that touch, which is the real goal and purpose of the use of this sense. As such, it is necessary to ignore these men or to listen to them while keeping this fact in mind. By what other means would they have us know when our opponent begins to act against us, so that we can counter him, if not by the sense of feel that comes from crossing swords, where we can detect when he is about to begin because the force of his blade against our own becomes lighter? The sense of feel tells us in half the time it takes for us to see what is happening. Finally, how else would they have it, that we can work with confidence against someone, if we do not have a sense of feel by which we can know with how much force, and on which side, our opponent is attacking? Considering these points, it is easy to see that those who hold as detrimental such a useful ability are holding to false doctrines. For as soon as we have crossed swords, we can approach our opponent with confidence, because we are certain to know in good time, all the designs he would undertake against. Designs which he cannot even begin to execute, but we are already prepared against him. This is such a notable advantage, one which has been in use in the Exercise of Arms for so long, yet without these masters having been able to see it. This is a skill so obvious, so important, and so necessary, that those who have not completely learned it have no better ability than one who has never touched a weapon in his life. And through ignorance of this, they hold the belief that approaching an opponent is so dangerous that they must make use of main-gauche, or two swords, as if the sword was not entirely sufficient in and of itself for both the defence of the of the holder and causing harm to an opponent. | + | | class="noline" | Toutes ces exemples demonſtrent clairement le tres-grand uſage du Sentiment, qui eſt toutesfois en ſi petite eſtime envers les Maiſtres de ceſte Profeſſion. Mais veu que la verité en eſt ſi evidente, ils ſont contraints malgré qu’ils en ayent, d’en recognoiſtre le forces. Car tout auſſi toſt qu’on les attaque la lame, ils s’en ſentent incommodez, & taſchent à la delivrer par touts moyens, ſoit en reculant, ſoit an cavant ſoit en uſant de feintes, ou meſmes de plus lourdes aćtions durant leſquelles il eſt neceſſaire qu’ils perdent touſiours autant de temps, duquel ils ſe pourroyent prevaloir à leur advantage, s’ils n’aimoyent pas de careſſer pluſtoſt leur ignorance, que d’apprendre à mieux faire. A tout le moins, puis qu’ils ſe ſentent incommodez par l’accouplement des lames, ils devroyent penſer s’ils en reçoivent quelque incommodité de leur part, qu’auſſi l’adverſaire en eſt pas libre, & puis que les incommoditez ſont plus grandes les unes que les autres, auſſi qu’elles peuvent eſtre augmentées en pourſuivant les meſmes commencements, & que elles peuvent eſtre remediés par leurs contraires. Ils devroyent adviſer à diminuer leurs propres incommodites, & à augmenter celle de leurs adverſaires par la moderation du Sentiment meſme, ſans perdre incontinent courage comme en une choſe deſeſperée, à laquelle il n’y a point de remede ſinon d’en eſchapper à touts marchez. Ce qui eſt tout au contraire. car l’experience non ſeulement nous demonſtre, que l’attouchement eſt de tres-grand importance pour le jugement & la cognoiſſance des choſes, mais qui plus eſt le commun langage nous apprend, qu’il ne peut y avoir aſſeurance plus certaine que celle qu’on touche à la main. Nous voyons que les aveugles congnoiſſent au ſeul ſentiment les differences de la monnoye, qu’à l’aide d’iceluy ils trouvent les chemins pour arriver par tout où ils pretendent; & à l’exemple deſquels quand nous nous trouvons en obſcurité, nous faiſons de meſme: & puis qu’en ceſt Exercice des Armes il eſt queſtion de diſcerner le fort & le foible des mouvements du Contraire, par quel moyen veulent ils donc qu’on les puiſſe comprendre, ſinon par le ſentiment & par l’attouchement des eſpees, & puis que le fort & le foible, ſont le propre objećt du ſentiment: en ſorte que’il eſt neceſſaire de les ignorer ou de les entendre par ceſte voye ſeule. Par quel moyen veulent ils qu’on comprenne les commencements des meſmes mouvements du Contraire, pour travailler à temps alencontre, ſinon par l’attouchement, auquel les commencements ſe deſcouvrent par leur foibleſſe, touſiours un demy temps pluſtoſt qu’ils ne ſe peuvent appercevoir à la veuë. Et finalement comment veulent ils, qu’on travaille avec aſſeurance alencontre, ſi on n’a pas l’attouchement par lequel on cognoiſſe avec quelle force, & de quel coſté l’adverſaire travaille. Par leſquelles conſiderations, il ſe voit que ceſt à fauſſes enſeignes, qu’ils tiennent pour dommageable ce qui eſt en effećt ſi Vtile. Car dés que nous avons l’attouchement des lames, nous pouvons faire nos approches deſſus l’adverſaire avec aſſeurance, puis que nous ſommes certains de ſçavoir touſiours à temps les deſſeings qu’ils voudra faire, leſquels il ne pourra tant ſeulement commencer que nous ne ſoyons deſia preparez alencontre. Advantage ſi notable, & ſi digne, que c’eſt choſe admirable, comment l’Exercice des Armes a eſté ſi longuement en vogue, ſans que les Maiſtres s’en ſoyent apperceus, eſtant choſe ſi claire, ſi ample, & ſi neceſſaire, qu’au defaut de l’avoir pratiquée, ils ſe voyent à touts moments, comme reduits à l’eſgal de ceux qui jamais n’ont manié les armes. Et pour l’ignorance de laquelle, ils tiennent les approches ſi dangereuſes, qu’ils en ſont contraints de ſe ſervir inutilement de la main gauche, ou d’Armes doubles, comme ſi l’eſpee neſtoit auſſi bien ſuffiſante à defendre la perſonne qui en uſe, comme elle eſt capable à offencer le Contraire. |

| − | |||

| − | |Toutes ces exemples demonſtrent clairement le tres-grand uſage du Sentiment, qui eſt toutesfois en ſi petite eſtime envers les Maiſtres de ceſte Profeſſion. Mais veu que la verité en eſt ſi evidente, ils ſont contraints malgré qu’ils en ayent, d’en recognoiſtre le forces. Car tout auſſi toſt qu’on les attaque la lame, ils s’en ſentent incommodez, & taſchent à la delivrer par touts moyens, ſoit en reculant, ſoit an cavant ſoit en uſant de feintes, ou meſmes de plus lourdes aćtions durant leſquelles il eſt neceſſaire qu’ils perdent touſiours autant de temps, duquel ils ſe pourroyent prevaloir à leur advantage, s’ils n’aimoyent pas de careſſer pluſtoſt leur ignorance, que d’apprendre à mieux faire. A tout le moins, puis qu’ils ſe ſentent incommodez par l’accouplement des lames, ils devroyent penſer s’ils en reçoivent quelque incommodité de leur part, qu’auſſi l’adverſaire en eſt pas libre, & puis que les incommoditez ſont plus grandes les unes que les autres, auſſi qu’elles peuvent eſtre augmentées en pourſuivant les meſmes commencements, & que elles peuvent eſtre remediés par leurs contraires. Ils devroyent adviſer à diminuer leurs propres incommodites, & à augmenter celle de leurs adverſaires par la moderation du Sentiment meſme, ſans perdre incontinent courage comme en une choſe deſeſperée, à laquelle il n’y a point de remede ſinon d’en eſchapper à touts marchez. Ce qui eſt tout au contraire. car l’experience non ſeulement nous demonſtre, que l’attouchement eſt de tres-grand importance pour le jugement & la cognoiſſance des choſes, mais qui plus eſt le commun langage nous apprend, qu’il ne peut y avoir aſſeurance plus certaine que celle qu’on touche à la main. Nous voyons que les aveugles congnoiſſent au ſeul ſentiment les differences de la monnoye, qu’à l’aide d’iceluy ils trouvent les chemins pour arriver par tout où ils pretendent; & à l’exemple deſquels quand nous nous trouvons en obſcurité, nous faiſons de meſme: & puis qu’en ceſt Exercice des Armes il eſt queſtion de diſcerner le fort & le foible des mouvements du Contraire, par quel moyen veulent ils donc qu’on les puiſſe comprendre, ſinon par le ſentiment & par l’attouchement des eſpees, & puis que le fort & le foible, ſont le propre objećt du ſentiment: en ſorte que’il eſt neceſſaire de les ignorer ou de les entendre par ceſte voye ſeule. Par quel moyen veulent ils qu’on comprenne les commencements des meſmes mouvements du Contraire, pour travailler à temps alencontre, ſinon par l’attouchement, auquel les commencements ſe deſcouvrent par leur foibleſſe, touſiours un demy temps pluſtoſt qu’ils ne ſe peuvent appercevoir à la veuë. Et finalement comment veulent ils, qu’on travaille avec aſſeurance alencontre, ſi on n’a pas l’attouchement par lequel on cognoiſſe avec quelle force, & de quel coſté l’adverſaire travaille. Par leſquelles conſiderations, il ſe voit que ceſt à fauſſes enſeignes, qu’ils tiennent pour dommageable ce qui eſt en effećt ſi Vtile. Car dés que nous avons l’attouchement des lames, nous pouvons faire nos approches deſſus l’adverſaire avec aſſeurance, puis que nous ſommes certains de ſçavoir touſiours à temps les deſſeings qu’ils voudra faire, leſquels il ne pourra tant ſeulement commencer que nous ne ſoyons deſia preparez alencontre. Advantage ſi notable, & ſi digne, que c’eſt choſe admirable, comment l’Exercice des Armes a eſté ſi longuement en vogue, ſans que les Maiſtres s’en ſoyent apperceus, eſtant choſe ſi claire, ſi ample, & ſi neceſſaire, qu’au defaut de l’avoir pratiquée, ils ſe voyent à touts moments, comme reduits à l’eſgal de ceux qui jamais n’ont manié les armes. Et pour l’ignorance de laquelle, ils tiennent les approches ſi dangereuſes, qu’ils en ſont contraints de ſe ſervir inutilement de la main gauche, ou d’Armes doubles, comme ſi l’eſpee neſtoit auſſi bien ſuffiſante à defendre la perſonne qui en uſe, comme elle eſt capable à offencer le Contraire. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 4,858: | Line 4,843: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 4,866: | Line 4,851: | ||

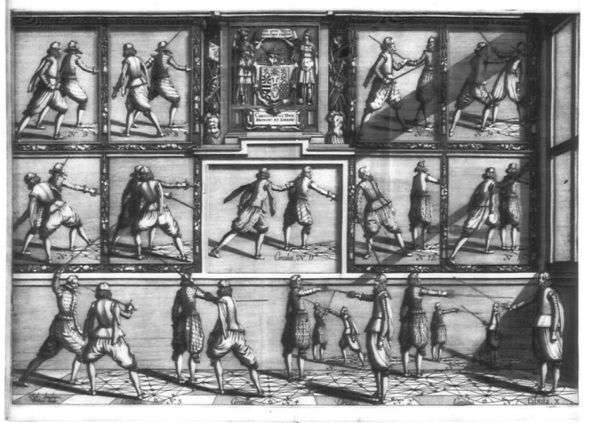

|Colspan="2"|[[file:Thibault L1 Tab 10.jpg|600px]] | |Colspan="2"|[[file:Thibault L1 Tab 10.jpg|600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | N.B., The coat of arms at the top belongs to [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian,_Duke_of_Brunswick-Lüneburg Christian (the Elder)] (1566 - 1633), Duke of Brunswick and Lunenbourg. | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; font-size: 16pt; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; font-size: 16pt; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| Line 5,117: | Line 5,104: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | Those who my chance to contemplate the images without duly examining them, may feel they have some critique to make. They may not be easily persuaded that is practicable, when confronted with a live opponent, to use these means to get behind him, as shown. Also that this said opponent would take care not to permit this. But I would caution them, that they would but take some time to consider the opening Zachary created, the extremity of the position into which Zachary has been put, before they proudly present their case. The strike that Alexander makes can only be countered with an extremely powerful and violent parry. And such wild action cannot be conducted, nor controlled, as easily as one wishes, the opponent has benefitted from having already moved into close range, and while the swords were flying overhead, he has taken the opportunity and time to pass beyond and behind. Those who find this so very strange are those who have been trained in the traditional way, who are careful to only make a pass while they are still at long range, and upon seeing their opponent’s sword close in, withdraw out of range. What they do by chance, we perform with assurance. For we come from the sense of feel and the close range, and thereby force our opponent to counter our moves wildly, in such a way that opens to us the path for our position, from which he invariably receives a blow. | |