|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli"

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter I: Of Fencing in general''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter I:'''</p> |

| − | 1 | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''Of Fencing in general'''</p> |

| − | 1 | + | |

| + | <p>[1] There is nothing in the world to which Nature, wise mistress and benign mother of the universe, with greater genius, and more solicitudinous regard, than for the conservation of one’s self provides him (of which Man is, more so than any other noble creature, demonstrating himself very dear of his safety), as the singular privilege of the hand, with which not only does he go procuring all things necessary for the sustenance of his life, but if he arms himself yet with the sword, noblest instrument of all, protects and defends himself, against any willful assault of inimical force; nonetheless following the strict rule of true valor, and of the art of fencing.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/18|1|lbl=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 2 | + | | <p>[2] Hence if one would clearly discern how necessary to man, how useful, and honorable may be the said discipline, and how it is that to everyone it may be necessary, and good to them, and maximally in demand, those armed of singular valor are inclined to the noble profession of the military, to which this science is subordinate in the guise of an alternative or subservient discipline, as is the part to the whole, and the end of the middle is subject to the final end.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/18|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 3 | + | | <p>[3] The aim of fencing is the defense of self, from whence it derives its name; because “to fence” does not mean other than defending oneself, hence it is that “protection” and “defense” are words of the same meaning; whence one recognizes the value and the excellence of this discipline is such that everyone should give as much care thereunto, as they love their own life, and the security of their native land, being obligated to spend that lovingly and valorously in the service thereof.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/18|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 4 | + | | <p>[4] Thence it is yet seen that defense is the principal action in fencing, and that no one must proceed to offense, if not by way of legitimate defense.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/18|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 5 | + | | <p>[5] The effective causes of this discipline are four. Reason, nature, art, and practice. Reason, as orderer of nature. Nature, as potent virtue. Art, as regulator and moderator of nature. Practice, as minister of art.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/18|5|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/19|1|lbl=2|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 6 | + | | <p>[6] Reason orders nature, and the human body in fencing, is its defense, in reason is considered judgment and volition. Judgment discerns and understands that which must be done for its defense. Volition inclines and stimulates one to the preservation of self.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/19|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 7 | + | | <p>[7] In the body, which in the guise of servant executes the commandments of reason, is to be considered in the body proper greatness: in the eyes the vitality, and in the legs, in the body, and in the arms, the agility, vigor, and quickness.</p> |

| − | | | + | |{{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/19|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 8 | + | | <p>[8] Nature orders and prepares matter, is the sketch, is the accommodation to such extent in order to contain the final form and perfection of art.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/19|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 9 | + | | <p>[9] Art regulates nature, and with more secure escort guides us according to the infallible truth, and by the ordinance of its precepts to the true science of our defense.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/19|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 10 | + | | <p>[10] Practice conserves, augments, stabilizes the strength of art, of nature, and more so than science, begets in us the prudence of many details.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/19|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 11 | + | | <p>[11] Art regards nature and sees that owing to the small capacity of matter, it cannot do all that which it intends to do, and however considers in many details its perfections and imperfections, and in the guise of architect takes thereof and makes such a beautiful model that it is thus refined, and sharpens the rough-hewn things of nature, reducing them little by little to the height of their perfection.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/19|7|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 12 | + | | <p>[12] From nature art has undertaken in defending oneself the ordinary step, the third guard for resting in defense, and the second and fourth for offense, the tempo, or the measure, and the manner as well of the placement of the body, with the torso now placed above the left leg for self-defense, now thrown forward and carried on the right leg in order to offend.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/19|8|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 13 | + | | <p>[13] Because without doubt the first offenses were those of the fists, in the making of them is seen the ordinary step. The third, the second, and fourth, it is yet seen, that many do the punch mostly in tempo and measure.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/19|9|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 14 | + | | <p>[14] Against this offense of the fist, of course was found the art of the stick, and this defense not yet sufficing, iron; I believe it is, that of this material were made little by little many diverse weapons, but always one more perfect than all others, owing to the multiplicity of its offenses, to wit that the sword was discovered, the perfect weapon, and proportioned to the proper distance, in which mortals naturally can defend themselves.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/20|1|lbl=3}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 15 | + | | <p>[15] The weapons which are of length exceeding the distance of natural defense and offense are discommodious and abhorrent for use in civic converse, and the excessively short ones are insidious and with danger to life; owing to which, in republics founded upon justice of good laws, and of good customs, it always was, and is, prohibited to carry arms of which can be born treacherous and heedless homicides. On the contrary, in the ancient Roman republic, the true ideal of a good government, the use of arms was entirely prohibited, and to no one, however noble and great that there was, was it licit to carry a sword or other weapon, except in war, and those who in time of peace were discovered with arms, were proceeded against as against murderers.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/20|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 16 | + | | <p>[16] And the Roman soldiers, immediately upon arriving home, put down their arms together with their short uniforms, and soldiery, and assumed again their long civil robes, and attended to the studies and the arts of peace, because no Roman exercised the body (as says Salustio) without the brain, each one attending beyond the studies of war, to each office of peace, therefore desirous, the burden of war, themselves supported, and yet immediately upon the end of war, they heard no more of captain, of soldier, nor of military wages.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/20|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 17 | + | | <p>[17] In these times soldiers are a greater burden to Princes and to Lords, and more so to the populace in times of peace than in war, and because they are not trained in other studies than those of war, they hate peace, and much of the time they are the authors of turbulence and wretched counsel.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/20|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 18 | + | | <p>[18] But turning to our matter, I say that the sword is the most useful and just arm, because it is proportioned to the distance at which offense is naturally performed, and all arms, to the degree that they differ from this distance of natural defence and offense, are to that extent more bestial and adverse to nature, and therefore useless to civic converse; the one is the way of virtue and of true reason, and the other burdensome and coarse, from which nature never departs, keeping company with sin and ignorance, and sliding about by many routes; one is the straight line, which none but the artful knows how to do; the oblique lines are infinite, and anyone can do them. Whence in our times we see offenses and defences multiply themselves and the art unto infinity, human endeavour imitating nature from principles; and while it follows the traces thereof it is useful and advantageous to the human life, but as soon as it departs from the footprints of nature, it begins to degenerate from the nobility of its origin, and hurls itself into the snares of harmful fancy, and plunges human kind into the abyss of ignorance, leading it from the age of gold into the filthiness of mud.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/20|5|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/21|1|lbl=4|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 19 | + | | <p>[19] From the force of nature, art, and practice, as efficient causes of the defense of which, up until now we have treated, is born the advantage and disadvantage of arms, but principally derives from the just height of body and from the length of the sword; because a man, large of frame, and that carries a sword proportioned to his body, without doubt will come first to the measure. In regard of this, in order to compensate for the natural imperfections of those who are found to be inferior of height, I believe, that it is prohibited in certain lands to make the blade of a sword longer than another, which does not seem a just thing, that one, who is through nature superior, loses advantage still from art, necessitating to him to suffice the privilege of nature, which without manifest indignity, wanting to equalize him with the smaller, not able to take away from him in general, with bestowing a sword less long to him, than to those who are short, who by chance could have other advantages of art and of practice, which exceed those of nature, in which cases human prudence is not sufficient to provide imparticular things.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/21|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 20 | + | | <p>[20] The art of fencing is most ancient, and was discovered in the times of Nino, King of the Assyrians, who, through use of the advantage of arms, was made monarch and patron of the world; from the Assyrians the monarchy passed to the Persians; the praise of this practice, through the valor of Ciro, from the Persians, came to the Macedonians, from these to the Greeks, from the Greeks it was fixed in the Romans, who (as testifies Vegetius) delivered in the field masters of fencing, whom they named “Campi doctores, vel doctores” which is to say, guides, or masters of the field, and these taught the soldiers the strikes of the point and of the edge against a pole. Nowadays we Italians equally carry the boast in the art of fencing, although more in the schools than in the field, and in the use of the militia, considering that in these times war is made more with artillery, and with the arquebus, than with the sword, which moreover almost will not serve in order to secure victory.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/21|3|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/22|1|lbl=5|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 21 | + | | <p>[21] This discipline is art, and is not science, taking that is, the word “science” in its strictest sense, because it does not deal with things eternal, and divine, and that surpass the force of human will, but it is art, not done from manuals, but rather active, and serves very closely the civil science; because its effects pass together with its operation, in the guise of virtue, and being passed, they do not leave any chance of labor or of manufacture, as are employed in performing the plebian and mechanical arts, all of which, although some of them are celebrated with the name of nobility, at great length it surpasses and exceeds.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/22|2|lbl=-}} |

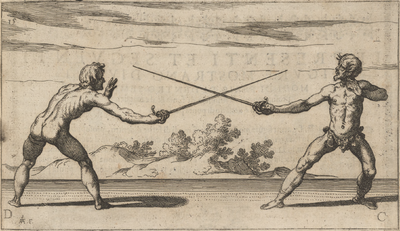

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 22 | + | | <p>[22] The material of fencing is the precepts of defending oneself well with the sword; its form, and the order is the truth of its rule, always true and infallible.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/22|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 23 | + | | <p>[23] But it is time at last, that gathering all up, which heretofore we have said in brief words, we come to lay the foundation of this discipline, which is its true and proper definition, following the rule from which we will guide and direct the rest of all its precepts.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/22|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter II: The definition of fencing, and its explanation.''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter II:'''</p> |

| − | 24 | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''The definition of fencing, and its explanation.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[24] Fencing is an art of defending oneself well with a sword.</p> | ||

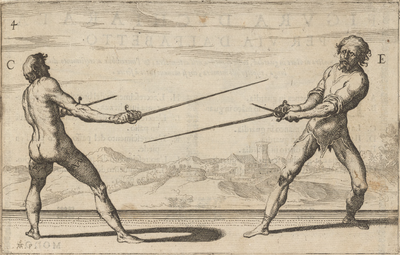

| + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/22|5|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 25 | + | | <p>[25] An art, because it is an assembly of perpetually true and well-ordained precepts, useful to civil converse.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/22|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 26 | + | | <p>[26] The truth is a disposition of precepts of fence; it must not be measured following the ignorance of some, who teach and write owing to the long use of arms that they have; and not owing to knowledge, but rather more often they make of shadow, substance; and of chance, reason; mixing gourds with lanterns, and pole-vaulting in shrubbery; but one must esteem those who constrain themselves to the truth of its nature.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/23|1|lbl=6}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 27 | + | | <p>[27] Their utility is manifest, because they teach the mode of defense, that is very naturally just, and honest, and that cannot be doubted to be of the greatest utility that it delivers to human life, because daily they discern it manifestly in its effects. For as much as that the sword is a commodious weapon to defend oneself in just distance, in which one and the other can naturally offend, we see that the combatants, almost always resting in the defense, rarely come to the offense, which is the last remedy for saving their life, which they would not have, if the arms were disproportionate, that is, either greater or lesser than the natural defense looks for.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/23|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 28 | + | | <p>[28] The aim which separates fencing from all other sciences, is to defend oneself well, however with the sword.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/23|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter III: The division of fencing that is posed in the knowledge of the sword.''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter III:'''</p> |

| − | 29 | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''The division of fencing that is posed in the knowledge of the sword.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[29] There are two parts to fencing, the knowledge of the sword, and its handling. The knowledge of the sword is the first part of fencing, that teaches to know the sword to the end to handle it well.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/23|4|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 30 | + | | <p>[30] The sword therefore is a pointed arm of iron, and apt to defend oneself in distance, in which one and the other can naturally and with danger of body offend.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/23|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 31 | + | | <p>[31] The material of the sword is the iron material of defense; without doubt it is found against that of wood it suffices little to beat aside, and disdain the injury, that one does daily to another.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/23|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 32 | + | | <p>[32] Its exterior form is that it is pointed; because if it were blunt, it would not serve to hold the adversary at the distance of natural offense.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/24|1|lbl=7}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 33 | + | | <p>[33] Its purpose is chiefly that of defense, which signifies chiefly to hold the adversary at a distance such that he cannot offend me, which sort of defense, and natural limits, enabling it to put into action, without injury of my fellow man. And in the Latin tongue, as it is already heard said with grammatical certainty, “defend” does not mean other than “avoid”, or truly to distance oneself from a thing that can harm, if one comes too near thereunto.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/24|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 34 | + | | <p>[34] Hence the words “to defend” signify “to offend”, and strike, which is the ultimate and subsidiary remedy of defense, in case the enemy should pass the boundary of the first defense, and advance himself near to such extent, that I came in danger of coming to harm from him, were I not to take heed for myself; because of the fact, that the enemy crosses the boundaries of defense, entering into those of offense, I am no longer obligated to carry any respect for the conservation of his life, as he comes to my turn, with some arm, commodious to harm me, naturally indeed, as I say in the distance of being able to arrive to me.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/24|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 35 | + | | <p>[35] The purpose of the sword, which is to defend oneself in the said distance, is measured in its length.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/24|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 36 | + | | <p>[36] Therefore the sword has as much for its length as twice that of the arm, and as much as my extraordinary step, which length corresponds equally to that which is from the placement of my foot, as far as it is beneath the armpit.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/24|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 37 | + | | <p>[37] There are two parts to the sword: the forte, and the debole. The forte begins from the hilt, extending as far as the middle of the blade; and the remainder is called the debole. The forte is for parrying, and the debole for striking.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/24|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 38 | + | | <p>[38] The edge is false, and true. The true is that which faces downward when the hand rests in its natural position, which, turning itself out, or from inside, outwards from its natural orientation, makes the false edge. The first orientation, that is, of the true edge, is to be recognized in third, which is the position of the sword in guard, and the other, that is, of the false edge, will appear manifested in the position of third, and second, which are orientations of the sword, not in guard, but in striking.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/24|7|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 39 | + | | <p>[39] I divide only the debole into the true and false edges, and not the forte, because the consideration does not occur that is made in the forte, which serves no other purpose than to parry, and were it without edge, and dulled, it would not be at all amiss, in place of point in the forte and the hilt, not only for gripping the sword, but also for covering oneself and chiefly the head in striking.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/24|8|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/25|1|lbl=8|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter IV: On Measure''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter IV:'''</p> |

| − | 40 | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''On Measure.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[40] Up until now we have discussed the first part of fencing, which consists of the knowledge of the sword; now we commence to treat of the second part, which is that of its handling.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/25|2|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 41 | + | | <p>[41] The handling of the sword is the second part of fencing, which shows the way of handling the sword, and is distributed among the preparation of the defense, and in the same defense, the preparation, and, in the first part of the handling of the sword, that places the combatants in just distance, and in convenient posture of body in order to defend themselves in tempo; and has two parts; in the first is discussed measure and tempo.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/25|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 42 | + | | <p>[42] In the second is treated of the disposition of the limbs of the body.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/25|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 43 | + | | <p>[43] Measure is taken for a certain distance from one end to the other, as for example in the art of fencing is taken for the distance that runs from the point of my sword to the body of the adversary, which is wide or narrow. From then it is taken for an apt thing to measure the said distance, which in the use of fencing is the natural braccio,<ref>I.e. arm length.</ref> which measures all distances, which in the exercise of this art, has all the qualities, and conditions, that are expected of an accomplished measure.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/25|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 44 | + | | <p>[44] The measure is a just distance, from the point of my sword to the body of my adversary, in which I can strike him, according to which, is to be directed all the actions of my sword, and defense.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/25|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 45 | + | | <p>[45] The narrow measure is of the foot, or of the right arm; the measure of the foot is of the fixed foot, or of the increased foot.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/25|7|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 46 | + | | <p>[46] The wide measure is, when with the increase of the right foot, I can strike the adversary, and this measure is the first narrow one.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/26|1|lbl=9}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 47 | + | | <p>[47] The narrow fixed foot measure is that in which only pushing the body and leg forward, I can strike the adversary.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/26|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 48 | + | | <p>[48] The narrowest measure is when the adversary strikes at wide measure, and I can strike him in the advanced and uncovered arm, either that of the dagger or that of the sword, with my left foot back, followed by the right while striking.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/26|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 49 | + | | <p>[49] The first wide measure is of a tempo and a half, the second is of a whole tempo, the third is of a half tempo, regarding the three distances, which according to their size require more or less speed of tempo, and this is enough to have said of measure. Following now is the doctrine of tempo.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/26|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter V: Of Tempo''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter V:'''</p> |

| − | 50 | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''Of Tempo.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[50] The word “tempo” in fencing comes to signify three different things; chiefly it signifies a just length of motion or of stillness that I need to reach a definite end for some plan of mine, without considering the length or shortness of that tempo, only that I finally arrive at that end. As in the art of fencing in order to come to measure, I need a certain and just tempo of motion and of stillness, it doesn’t matter whether I arrive there either early or late, provided that I reach the desired place. We pose the example that I move myself to look for the measure, and that I go very slowly to find it, and that my adversary is so much fixed of body that I find it, although I have arrived somewhat late, nonetheless not at all can it jeopardize my plan; because I have arrived in tempo, considering that, as much length of time as I am myself in motion, precisely so much had my adversary fixed himself; thus my motion equals the tempo of the stillness of my adversary, and his stillness measures my motion precisely, and because in remaining in guard, and searching for the measure, is only to be considered the correspondence of the tempo, that the combatants in moving themselves, and in fixing themselves, mutually consume, that they arrive to a certain point of measure; according to this, in the said actions, the speed of the motion, and the shortness of the stillness do not come into consideration, but rather through taking the just measure, it is more useful that they go, as is often said, with a leaden sandal, with the weight counterpoised, and placed over the left leg in ordinary pace, a posture of body most apt for coming with consideration and with respect to apprehend the due measure.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/26|5|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/27|1|lbl=10|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 51 | + | | <p>[51] Next this word “tempo” is taken in the sense of quickness, in respect of the length or brevity of the motion or of the stillness. Thus in the art of fencing there are three distances, and different measures of striking, and through this again are found three distinct tempos, and here it is not wished to consider only that one comes to a certain end, but that one arrives also with a certain quickness and velocity, because the wide measure, that is, of the increased foot, requires a tempo, that is, a severing of stillness, either of movement of the sword, or of the bodies of the combatants, fairly brief, but not so brief as the narrow measure of the fixed foot; and the narrowest measure requires a fastest tempo, because each little bit that I move myself with the point of my sword, and each little bit that my adversary fixes himself, in the distance of narrowest measure, suffices me to effect my plan, because this tempo is briefest; however we will call it half a tempo, and consequently the tempo that is spent in striking from the less narrow measure of the fixed foot will come to make a whole tempo, and the last tempo, which is employed in striking from wide measure, which is of the increased foot, will be a tempo and a half.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/27|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 52 | + | | <p>[52] In the first tempo, which is that of seeking the wide measure, one does not consider the quickness of the motion and of the stillness, nor is it necessary to measure it by half of a whole tempo, which manners of tempos are only to be regarded in striking. By which thing the posture of the body in the striking is entirely contrary to that which is observed in seeking the narrow measure; because the first posture is comfortable for going little by little to find the narrow measure, and the other is bold, and with speed one hurls oneself to strike.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/27|3|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 53 | + | | <p>[53] The tempo is not other than the measure of the stillness and of the motion; the stillness of the point of my sword measures the motion of the body of my adversary, and the motion of my adversary with his body measures the stillness of the point of my sword. Now, so that this tempo may be just, it is necessary that as much length of tempo as the body of my adversary is fixed, so much is the point of my sword moved, and thus, consequently, for example: I find myself in wide measure, with a will to come to narrow measure; now I move the point of my sword to come to the said terminus; meanwhile as I move myself it is necessary that my adversary fix his body, and thus the stillness of body of my adversary is the measurement of the point of my sword; and, however, if I moved myself to strike before my adversary finished fixing himself, because the tempo would be unequal, I would move myself in vain, or not without great danger to myself. We pose the case, that both of us move ourselves to find the measure, and the one and the other give each other to intend to have found it; both going to invest themselves, intervene so that the one and the other don’t hit, because the tempo in which they move themselves to strike won’t be just, in respect of the distance to which they must first arrive; in this example it is seen that the motion of my point measures the motion of the body of my adversary, and the motion of the point of my adversary measures the motion of my body. However in the times to come, many strike each other in contra tempo, having come at the same time to narrow measure.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/28|1|lbl=11}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 54 | + | | <p>[54] The tempo that has to be considered in wide measure requires patience, and that of the narrow measure, quickness in striking and in exiting.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/28|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 55 | + | | <p>[55] The tempo of the narrow measure is lost either through shortcoming of nature, or through defect of art and of practice.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/28|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 56 | + | | <p>[56] Through shortcoming of nature, by too much slowness of the legs, of the arm, and of the body, which derives either from weakness or from too much bodily weight, as we see to come to men who are either too fat or too thin.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/28|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 57 | + | | <p>[57] Through defect of art, when one does not learn to find the narrow measure as is necessary, with weight carried on the left leg, with the ordinary pace, and with the right arm extended, because the things must move in company in order to produce one single effect, yet they have to move in a just distance; but if the point of the sword is very advanced and the leg back, or if the leg is advanced and the arm back, then the sword will never be carried with that promptness, justness, and speed, which is required; by which, those who come to find the narrow measure in disproportionate distance of limbs, although they arrive there, nonetheless they cannot be in tempo of striking, because they would lack the best tempo of the narrow measure, which is that of prompt justness, or quickness.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/28|5|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/29|1|lbl=12|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 58 | + | | <p>[58] Through lack of practice, tempo is lost for the reason that the body is not yet well loose of limb, or when the scholars acquire some wretched habit, going back to the vanities of feints, and disengages, and counter-disengages, and similar things thus done.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/29|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 59 | + | | <p>[59] From this, which we have so far said, everyone will easily be able to understand to be falsest that which many say, that tempo is taken solely from the movement that my adversary makes with his body and sword; but it is necessary to have equal regard for my own motion, and not only to my motion and that of the adversary, but as well to our stillnesses; because tempo is not solely a measure of motion, but of motion and stillness.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/29|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 60 | + | | <p>[60] And concluding this matter of tempo, I say that every motion and every stillness of mine and of my adversary make together a tempo, to such extant, that one and the other measures.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/29|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter VI: Of the body, and chiefly of the head.''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter VI:'''</p> |

| − | < | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''Of the body, and chiefly of the head.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[61] The head truly is the chief thing in this exercise; it lies indeed in its due place, because it is that which recognizes measure and tempo, hence it is necessary that it comes to be deployed in that place where it can serve as the sentinel, and reveal the land from every side.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/29|5|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 62 | + | | <p>[62] The placement of the head, which lies in guard, and in seeking the measure, up to now is just and convenient when together with the sword it makes one straight line; because in this manner the eyes see all the stillnesses and movements of the sword and of the body of the adversary, and will recognize immediately the parts that they must offend and defend; the head being posted on the said parts, is nonetheless able to cast all the visual rays in a straight line, which they could not do if the head were borne higher or lower, so that its visual rays could not radiate from every side, and thus they would not be quick to seize or flee the tempo.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/30|1|lbl=13}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 63 | + | | <p>[63] In lying in guard and in seeking the measure, the head reposes itself upon the left shoulder, and in striking it leans upon the right shoulder.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/30|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 64 | + | | <p>[64] In lying in guard and in seeking the measure, the head has to retire as much as is possible, and in striking one wishes to propel it forward as much as one can.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/30|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 65 | + | | <p>[65] In striking, the head will take care to be somewhat more to one side than to the other, according to whether one will strike to the inside or the outside, thus it will be covered by the hilt and the sword arm.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/30|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 66 | + | | <p>[66] Other placements and movements of the head which are made in passing, in fleeing, and in moving the body out of the way in diverse sorts of guards, and in infinite means of striking, cannot be accepted as good ones, because they deviate from the straight line, which is called by me that which divides my body through the flank together with that of the adversary, as on the contrary the oblique line I name that which runs outside my body or that of my adversary, of one party as of the other, following the rule by which all of the play of fencing has to be that of measuring.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/30|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter VII: Of the body.''' < | + | | <p>'''Chapter VII:''' |

| − | 67 | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''Of the body.'''<ref>I.e. the trunk.</ref> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[67] In resting in guard and in seeking the measure, the body needs to be bent, and slopes to the rear, such that the angle which it makes with the right thigh is barely visible, and with the left thigh it comes to make an obtuse angle, so that the left shoulder is in line with the line of the left foot, and the right shoulder evenly passes through the middle of the pace of the guard.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/31|1|lbl=14}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 68 | + | | <p>[68] In striking the body propels itself forward, so that the right thigh forms an obtuse angle with the body, and the point of the shoulder is in line with the point of the right foot, and the left thigh and calf carry themselves forward on the diagonal in an oblique line, extended to such a degree that the left shoulder divides the pace that is made through the middle.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/31|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 69 | + | | <p>[69] And when one goes to strike, the body needs to be pushed forward in a straight line, so that the diversity of striking, outside and inside, leaning somewhat more to one than to the other side, will deviate the least from the straight line.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/31|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 70 | + | | <p>[70] The objective of why the body should be thus angled, and this is of prime importance, is because in this way the parts which can be offended are more distanced, and more covered, and better guarded, and defended; because the more distant a target is, the more difficult it is to strike it; thus in striking the blows are carried longer, faster, and more vigorously, thus as much further away do the offenses originate, to such a degree are they safer and better.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/31|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 71 | + | | <p>[71] In addition to the bending of the body and of its form, which it takes in putting oneself in guard, in seeking the measure, and in striking, is to be considered similarly its concealment, which diminishes its length, as the bend diminishes and contracts its height.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/31|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 72 | + | | <p>[72] The concealment of the body needs to be such that no more is shown than the middle of the breast, not only in fixing oneself in guard, and in seeking the measure, but also in striking, because as much less of the breast is shown, so much more one goes and strikes in a straight line, and as much more is uncovered, so much more of measure and of tempo is lost.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/32|1|lbl=15}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 73 | + | | <p>[73] They who like the guards, and counterguards, and stringering, here, there, above, and below, the feints, and counterfeints, the slope paces, the voids of the legs, and the crossings, necessarily form and move their bodies in many strange ways; which, as things done by chance and that were founded in no reasons that are sound and true, we will leave to their authors.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/32|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter VIII: Of the arms.''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter VIII:'''</p> |

| − | 74 | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''Of the arms.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[74] In resting in guard and in seeking the measure, the right arm must rest somewhat bent, so that its upper part is stretched in an oblique line, so low that the elbow meets the bend of the body, and is in line with the right knee; and its lower part, withdrawn somewhat, forms together with the sword a straight line.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/32|3|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 75 | + | | <p>[75] In resting in guard and in seeking the measure, the left arm together with the left thigh and calf have to serve as the counterweight of the body and the right leg; and the upper arm needs to be extended, so that it is in line with the left knee, and meets the bend of the left flank; and its forearm needs to be somewhat tucked in to oneself, in order by its motion to help to propel the body forward in striking, which it would not be able to do were it allowed to fall.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/32|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 76 | + | | <p>[76] In striking, the right arm needs to be extended in a straight line, turning the lower part of the hand and of the arm up, sometimes in, sometimes out, depending on from which side one strikes.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/32|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 77 | + | | <p>[77] In striking, the left arm needs to be so extended that it makes a straight line with the right arm, turning it according to whether one strikes outside or inside; because each iota that one carries the arm forward, or that one fixes it in an oblique line, would significantly diminish the measure, and the quickness of the tempo.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/33|1|lbl=16}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 78) The sword is regarded entirely as one limb with the arm, and it has to form a straight line with the forearm, which is properly aligned with the fold of the right flank, and has to divide the height and width of the body into two equal parts, because in resting in guard and seeking the measure, the reason why it will have to return properly to the fold of the flank is this: that every time that it is in this place, it will be quickest to come to the aid of all the parts that can be offended, being that the upper parts, that is, those from the top of the head down to the fold of the flank, are of a measure with the parts beneath from the fold of the flank down to the knee; and it doesn’t happen that one has to regard the calf, which being in the natural distance of the offense of the increased feet, cannot be offended without excessively leading one’s body forward into manifest peril. | + | | <p>[78]) The sword is regarded entirely as one limb with the arm, and it has to form a straight line with the forearm, which is properly aligned with the fold of the right flank, and has to divide the height and width of the body into two equal parts, because in resting in guard and seeking the measure, the reason why it will have to return properly to the fold of the flank is this: that every time that it is in this place, it will be quickest to come to the aid of all the parts that can be offended, being that the upper parts, that is, those from the top of the head down to the fold of the flank, are of a measure with the parts beneath from the fold of the flank down to the knee; and it doesn’t happen that one has to regard the calf, which being in the natural distance of the offense of the increased feet, cannot be offended without excessively leading one’s body forward into manifest peril.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/33|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 79 | + | | <p>[79] The location and posture of the sword in striking is entirely one with that of its arm, turning the false edge up in striking, according to whether it strikes from the outside or inside.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/33|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 80 | + | | <p>[80] Take heed diligently that the point of your sword always is aimed at the uncovered parts of the enemy, which are those of the right flank and right thigh, and one must not let anybody divert one from this intention through uncovering of the left parts, which is fallacious measure and tempo, being that it may be plucked back in an instant, which doesn’t occur with the right parts, which necessarily are made targets.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/33|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 81 | + | | <p>[81] It is not good to rest in guard with the arm crouched in, because it does not cover the measure well in which I find myself; it is equally not good for seeking the measure, because the point of the sword is too far from the body of the adversary. Hence one cannot take the proper measure, thereby lacking the ability to strike in tempo; in addition to this, the arm thus retired does not have separation from the adversary of just distance, wherein he can strike me, and thus it does not do its duty. Through which the sword is chiefly found thus to not be useful in striking, because it will not be able to strike in the measure of the increased foot, which resting with its point so far from the adversary, it cannot properly take the said measure, which is so much more excellent than the narrower measures, as it is to strike the enemy from afar than from near. Furthermore it is not good for launching the blow, which together with the arm is discharged by the pressure that makes the body advance, and it is not true that the stretching out of the arm increases the measure, but rather it is done well with the stretching of the body and of the forward pace, because the weight of the forward leg and the body, while extending the arm with the sword, is poised over the left leg, on which is supported the entire body and right leg; which left leg during the launching throws the body and the thigh forward onto the right leg, which mutually form a pillar and buttress, sustaining all of the weight of the body, inclined forward to launch the blow.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/33|5|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/34|1|lbl=17|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 82 | + | | <p>[82] I cannot approve of having the arm fully extended in guard and finding the measure, because it forces the sword out of the place which is proper and commodious to defend one’s own life, and to offend that of the adversary; and in striking it does not aid the body in launching the blow, and carries it with less vigor; other locations, and movements of the arm, are not desired in the play of striking in the straight line.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/34|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter IX: Of the thighs, calves, of the feet, and of the pace.''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter IX:'''</p> |

| − | 83 | + | |

| − | | ' | + | <p>'''Of the thighs, calves, of the feet, and of the pace.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[83] In resting in guard and in finding the narrow measure, the right calf with the thigh and its foot, point directly forward, and lean back in an oblique line, in the manner of a slope, and the left calf with the thigh and its foot point straight toward your left side, with the knee bent as far as a possible, so that the part inside the knee faces the point of the right knee.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/34|3|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 84 | + | | <p>[84] In striking, the knee of the right leg is bent so far as it can, so that the calf and the thigh come to make an extremely acute angle; and on the contrary, the left calf with its thigh is extended forward in an oblique line in the manner of a slope.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/34|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/35|1|lbl=18|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 85 | + | | <p>[85] The pace is a just distance between the legs, as much in fixing as in moving oneself, a point for placing oneself in guard for seeking the measure, and to strike; in regard of distance, the pace is either entirely narrow, or a half pace, or a just pace, or extraordinary.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/35|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 86 | + | | <p>[86] In the use of fencing, I know of no pace so good as the ordinary, in which the body rests commodiously and carried well in guard, for seeking the narrow measure with a little increase of pace; as wanting to seek it with smaller paces, the narrow foundation is weak; it would not support the weight of the body, and would disconcert one, if not little by little, but with paces and half paces one seeks the measure, and losing the tempo, would not discharge the blow with so much speed, and if they are indeed the said good paces, they will serve outside of the measure for walking, and placing oneself in guard, and for returning into it.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/35|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 87 | + | | <p>[87] The pace of fencing, we will, for better understanding, name “military”, or “soldierly”, dividing it into the ordinary and the extraordinary. The ordinary is that in which one rests in guard and seeks the narrow measure. And the extraordinary is that in which one moves, lengthening the pace forward to strike.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/35|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 88 | + | | <p>[88] The pace, regarding its position, is to be considered in more ways, forward, back, sideways, and diagonally, and this with the legs crossed or not, equally whether a single leg is moved or both, and whether the legs are moved to make an entire pace, either to diminish it or to change its position in order to allow the body to retreat or evade.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/35|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 89 | + | | <p>[89] It appears to me, that there are not but two main ways of fixing and moving oneself with respect to the legs. The first way is that in which one appears in guard, and seeking the narrow measure, or avoiding it; the other serves for striking.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/35|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 90 | + | | <p>[90] I do not know that stepping sideways serves other than to make a good show, and display animosity, and to scout out the strength of the adversary; when somebody goes to put himself in guard in this fashion of stepping, you will be able to avail yourself of all the narrow and just paces, although in my judgment in this the ordinary pace still carries the boast.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/35|7|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 91 | + | | <p>[91] Nonetheless there are those that avail themselves of this stepping to the side when the adversary is poised on an oblique line with the sword in order to stringer him on the outside, but to me it seems that it would be a more expeditious way to seek the narrow measure immediately by the straight line, which follows from the rule of the play thereof. Still, there are those who avail themselves thereof through fading back of the body, while their adversary comes to strike them encountering him in fourth, and in second, either from outside or inside, according to the occasion, but so would they be able to encounter him, having in consideration the tempo and the measure of fourth and of second in the straight line, without traversing their legs.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/35|8|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/36|1|lbl=19|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 92 | + | | <p>[92] The crossing of the left foot toward the right side in performing an inquartata is worthless; it causes a shortcoming, because it hinders the body and shortens the motion of the right arm in striking, with loss of tempo; the void of the right leg toward the left side from the adversary in order to perform an inquartata is equally a thing done by chance, and sooner serves for an amicable assault than for the trial or dispute.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/36|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 93 | + | | <p>[93] The passatas are not good, because they lose measure and tempo, because while one is moving the left leg, at the same time the torso, and the right leg, and the sword arm, cannot move to strike with due speed, nor without danger of risposta.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/36|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 94 | + | | <p>[94] Retreats are necessary principally in striking, because in the act of striking I necessarily uncover my body, yet as I fix myself too much it could easily occur that my adversary could make a response to me.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/36|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter X: Of defense, of the guard.''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter X:'''</p> |

| − | 95 | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''Of defense, of the guard.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[95] Up until now we have dealt of the first part of the handling of the sword, in which was taught to us the just distance, and the true position of all the members of the body, which are required for defense; now we will speak of that very same defense.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/36|5|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/37|1|lbl=20|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 96 | + | | <p>[96] Defense is the second part of handling of the sword, which trains us to employ the sword for our defense, and has two parts, of which the first is the defensive, or guard, as we wish to call it, and the other is the offensive.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/37|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 97 | + | | <p>[97] The guard is a position of the arm and of the sword extended in a straight line in the middle of the offendable parts, with the body well accommodated to its ordinary pace in order to hold the enemy at a distance from any offense, and in order to offend him in case he approaches to endanger you.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/37|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 98 | + | | <p>[98] The third then is exclusively a guard, not indeed posed with the hilt outside the knee, but so that it properly divides the body though the middle, neither high nor low, but just in the middle of the parts that cannot be covered, through being equally prompt and near to all of their offenses and defenses.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/37|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 99 | + | | <p>[99] The first and the second are not guards, because they are not apt for seeking the measure, and uncover too much of the body that can be offended and defended; the fourth equally shows too much of the body; it is a way of striking, and not of guarding oneself.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/37|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 100 | + | | <p>[100] There are three reasons which make it difficult to hit the mark, namely: the distance to the target; because it is concealed, so that one is at pains to see through the impediment of the things that veil it; and even if it is uncovered, as the danger of the blow approaches, in a moment it is possible to cover it.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/37|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 101 | + | | <p>[101] All of these virtues are contained in our guard; because it greatly distances the target and removes so much of it, that by means of the fold and concealment of the body, most of the parts that cannot be concealed can be excellently covered; one is quick to succor them, being in equal distance, and thus walks safely to take well the tempo and measure, which thing is the ultimate perfection of the guard.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/37|7|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 102 | + | | <p>[102] Of changing one’s guard, in guard, to me is not legitimate to speak, it not being good, if not a single guard.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/37|8|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 103 | + | | <p>[103] Offense is a defense in which I seek the measure and strike my adversary.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/37|9|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter XI: On the way of seeking the measure.''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter XI:'''</p> |

| − | 104 | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''On the way of seeking the measure.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[104] There are two arts to offense: seeking the measure, and striking.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/38|1|lbl=21}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 105 | + | | <p>[105] Seeking the measure is an offense in which, in the said guard, I seek the narrow measure in order to strike.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/38|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 106 | + | | <p>[106] There are three ways of seeking the measure; because I seek it, either while I move and the adversary fixes himself, or when I fix myself and the adversary moves, or when I move and the adversary moves.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/38|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 107 | + | | <p>[107] The tempo of these actions needs to be just, and equal to the final boundaries of the wide measure, upon which the tempo of seeking the measure expires, and gives rise to the tempo of another action, which is that of striking.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/38|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 108 | + | | <p>[108] In order that this tempo may be just, it is necessary that you have patience up until you arrive at the said distance, and move yourself earlier to strike.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/38|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 109 | + | | <p>[109] For example: I fix myself in guard to seek the measure, my adversary already being entered into the boundaries of offense; meanwhile, as he either seeks the measure, or pretends to strike me, he walks with his sword, it is necessary that I fix myself as much with the point of my sword, so that he arrives to the end of the wide measure, and I not move myself to strike earlier. Because in this action his motion has to measure my stillness, and my stillness his motion, and if I had moved myself from my stillness before he had come to the edge of the wide measure, the tempo would not be just, and I would not have sought the measure well; and in conclusion this motion and stillness are equal; so that one arrives to the principle that the narrow measure is one tempo, and it does not occur, however, as quick as it may be, that it may be equal and correspondent to the final terminus of the wide measure, and thus the end of the tempo of the wide measure is the beginning of the tempo of striking.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/38|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 110 | + | | <p>[110] Many in seeking the narrow measure make disengages and counterdisengages, feints and counterfeints, stringer a palmo<ref>a unit of measure variously from a palm’s width up to 10 inches</ref> and more of the sword, and step from every side, and twist their bodies and stretch them, and retreat in many eccentric fashions, which are things done outside of true reasons, and found through beguiling the doltish, and make the play difficult; nonetheless stringering of the sword, when I cannot do otherwise, seeking the measure in my guard, it is only necessary that I stringer the debole of my enemy’s sword in a straight line, with the forte of mine, and this straddling it without touching, but only in striking to hit with my forte the debole of the enemy’s sword, from the inside or the outside according to the circumstances of the striking.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/38|7|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/39|1|lbl=22|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 111 | + | | <p>[111] To disengage, although good, is good in the situation in which the adversary has constrained me and removed me from the straight line; in that case it would be licit, indeed necessary, to retreat, disengaging with a little ceding of my body or feet, replacing myself immediately into the straight line in order to seek the measure; because disengaging is done against stringering, and as stringering is done while moving the sword forward, thus must the disengage be done while retiring it.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/39|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Chapter XII: Of striking.''' | + | | <p>'''Chapter XII:'''</p> |

| − | 112 | + | |

| − | | '' | + | <p>'''Of striking.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>[112] Striking is the final offensive action of fencing, in which, having arrived at the narrow measure, I move myself, with my body, with my legs, and with my arms, all in one tempo thrown forward to be better able to strike my adversary, and this is done with the feet fixed or with the increase of the pace, according to the magnitude of the narrow measure, according to whether it comes to be more commodious for me to take more of one than of the other measure; because if through my tardiness, or through the fury of my adversary, the first measure vanishes, then I could avail myself of the second, striking with fixed feet, which in this case doesn’t happen, that greatly speeding the pace, with the bending only of the right knee, it does not behoove me to seek the narrower measure, so that I had time to increase the pace.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/39|3|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 113 | + | | <p>[113] Striking is done in three ways; because I can strike my adversary while I am fixed and he moves to seek the measure or to strike me; or while he is fixed and I move in order to seek the measure; or because both of us move ourselves to seek the measure and to strike; only this is the difference, that when he moves to strike me, I strike him with fixed feet, because when he moves through the said effect, I can poorly take the just measure to strike him with the increase of pace; on the contrary it is necessary that I cling to the narrower measure, and when he moves to seek the measure I strike him with the increase of pace.</p> |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/39|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/40|1|lbl=23|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 114 | + | | <p>[114] In consideration of the parts of the body with respect to the sword, I strike either from the inside or outside; from inside from fourth, and from outside from second, high or low according to the exposed parts of the body of the adversary, that he gives me measure, with respect to the point of my sword.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/40|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 115 | + | | <p>[115] Meanwhile, as I strike, I necessarily parry together, inasmuch that I strike in the straight line, and with my body in its due disposition, because when I strike in this manner, in tempo, and at measure, the adversary will never hit me, neither with point nor edge, because the forte of my sword goes in a straight line, and comes to cover all of my body.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/40|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 116 | + | | <p>[116] The edge is of little moment, because I cannot strike with the edge in the said distance of the narrow measure, without entirely uncovering myself and giving the measure and tempo to my adversary to strike me, because of the compass of the arm and of the sword which I make, and although some usefulness is found in the cut, nonetheless in the same measure in the very same tempo more can be shown in the thrust.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/40|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | 117 | + | | <p>[117] But without a trace of doubt, on horseback it is better to strike with the cut than the thrust, because my legs are carried by another’s, and thus I am not commodious to seek the measure and the tempo, which are apt for propelling forward the body and the arm, but it is indeed true that I can wheel my arm about to my satisfaction, which is a proper motion to strike with the edge.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf/40|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| class="noline" | | | class="noline" | | ||

| − | | class="noline" | '''Chapter XIII: Of the dagger.''' | + | | class="noline" | <p>'''Chapter XIII:'''</p> |

| − | Of the dagger it will suffice us in this brief chapter to record only that it has been found better for saving oneself, in case the adversary, while I throw a blow without attending to the parrying, threw one at me where it turned more commodious to him, than for one to be unable to employ the dagger in order to avert the risposta. And as all commodious things delivered carry along some incommodious ones, still thus did it happen to the play of the dagger, which one cannot employ without uncovering somewhat more of the body, and shortening a little the line while striking. This is the end of the dagger, but the art is deviated thereby from its chief aim, given to it as it is done with the sword, various effects which may be better put into action with the single sword, without going on further at such length. | + | |

| − | | class="noline" | '' | + | <p>'''Of the dagger.'''</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>Of the dagger it will suffice us in this brief chapter to record only that it has been found better for saving oneself, in case the adversary, while I throw a blow without attending to the parrying, threw one at me where it turned more commodious to him, than for one to be unable to employ the dagger in order to avert the risposta. And as all commodious things delivered carry along some incommodious ones, still thus did it happen to the play of the dagger, which one cannot employ without uncovering somewhat more of the body, and shortening a little the line while striking. This is the end of the dagger, but the art is deviated thereby from its chief aim, given to it as it is done with the sword, various effects which may be better put into action with the single sword, without going on further at such length.</p> | ||

| + | | class="noline" | {{pagetb|Page:Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli) 1601.pdf|41|lbl=24}} | ||

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 03:06, 20 July 2020

| Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 16th century |

| Died | 17th century |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Patron | Federico Ubaldo della Roevere |

| Influences | Camillo Aggrippa |

| Influenced | Sebastian Heußler |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) | Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (1610) |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |