|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Paulus Hector Mair

| Paulus Hector Mair | |

|---|---|

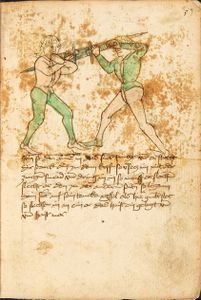

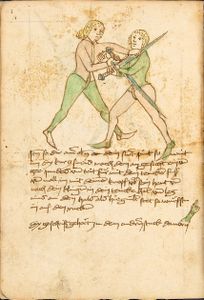

"Mair", Cod.icon. 312b f 64r | |

| Born | 1517 Augsburg, Germany |

| Died | 10 Dec 1579 (age 62) Augsburg, Germany |

| Occupation |

|

| Movement | |

| Influences | |

| Genres | |

| Language | |

| Notable work(s) | Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica |

| Manuscript(s) |

Codex Icon 393 I & II (1550s)

|

| First printed english edition |

Knight and Hunt, 2008 |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | Traduction française |

| Signature | |

Paulus Hector Mair (1517 – 1579) was a 16th century German aristocrat, civil servant, and fencer. He was born in 1517 to a wealthy and influential Augsburg patrician family. In his youth, he likely received training in fencing and grappling from the masters of Augsburg fencing guild, and early on developed a deep fascination with fencing manuals. He began his civil service as a secretary to the Augsburg City Council; by 1541, Mair was the Augsburg City Treasurer, and in 1545 he also took on the duty of Master of Rations.

Mair lead a lavish lifestyle and maintained his political influence with expensive parties and other entertainments for the burghers and patricians of Augsburg. Despite his personal wealth and ample income, Mair spent decades living far beyond his means and taking money from the Augsburg city coffers to cover his expenses. This embezzlement was not discovered until 1579, when a disgruntled assistant reported him to the Augsburg City Council and provoked an audit of his books. Mair was arrested and tried for his crimes, and hanged as a thief at the age of 62.

While Mair is not known to have ever certified as a fencing master, he was an avid collector of fencing manuals and other literature on military history, and some portion of his embezzlement was used to fund this hobby. Perhaps most significant of all of his acquisitions was the partially-completed manual of Antonius Rast, a Master of the Longsword and one-time captain of the Marxbrüder fencing guild. The venerable master died in 1549 without completing it, and Mair ultimately was able to produce the Reichsstadt "Schätze" Nr. 82 based on his notes. In sum, he purchased over a dozen fencing manuscripts over the course of his life, many of them from fellow collector Lienhart Sollinger (a Freifechter who lived in Augsburg for many years). After Mair's death, this collection was sold at auction as part of an attempt to recoup some of the funds Mair had embezzled.

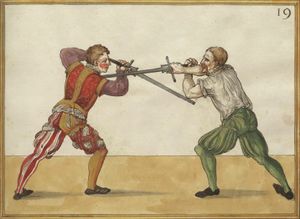

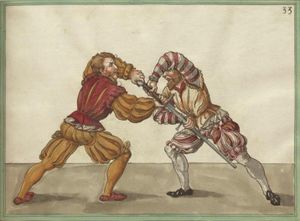

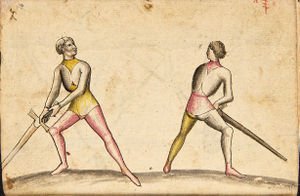

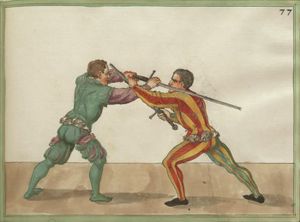

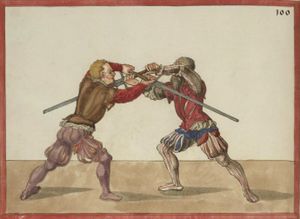

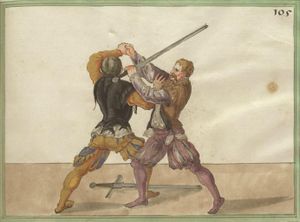

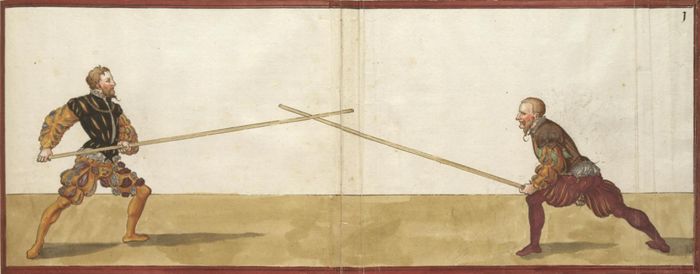

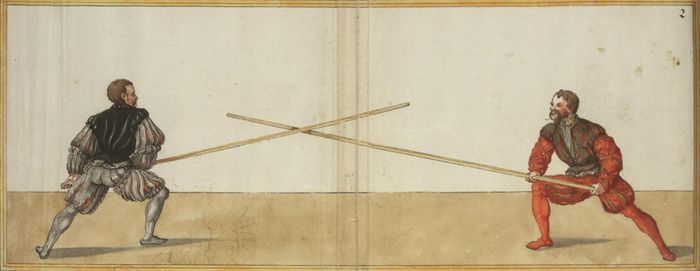

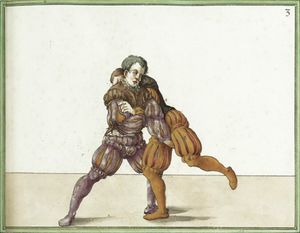

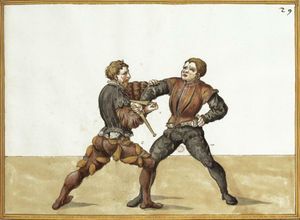

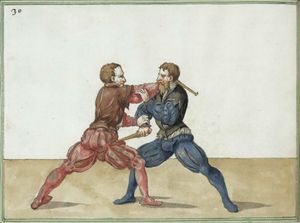

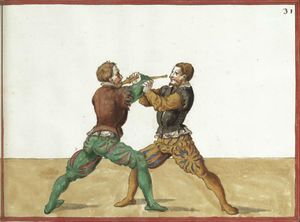

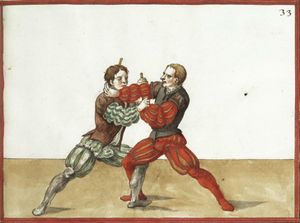

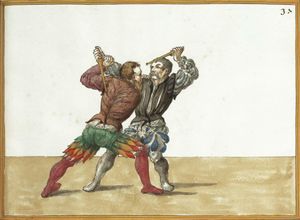

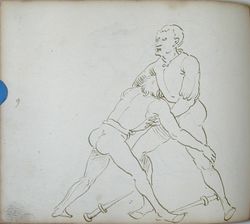

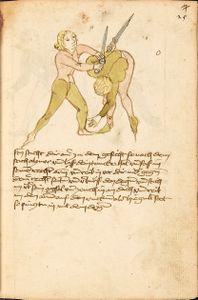

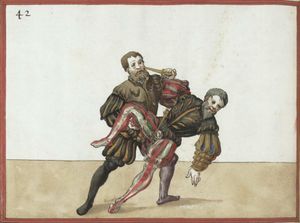

Like his contemporary Joachim Meyer, Mair believed that the Medieval martial arts were being forgotten; this was tragic to him, as he viewed the arts of fencing as a civilizing and character-building influence on men. In order to preserve as much of the art as possible, Mair commissioned a massive compendium titled Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica ("The Greatest Work on the Athletic Arts"), and in it he compiled all of the fencing lore that he could access. Some time in the 1540s, he retained famed artist Jörg Breu the Younger to create the illustrations for the text,[1] and hired two Augsburg fencers to pose for the illustrations.[2] This project was extraordinarily expensive and took at least four years to complete. Ultimately, three copies of the massive two-volume fencing manual were produced, each more ambitious than the last; the first was written in Early New High German, the second in New Latin, and the third incorporated both languages.

Whether viewed as a noble scholar who made the ultimate sacrifice for his art or an ignoble thief who robbed the city that trusted him, Mair remains one of the most influential figures in the history of Kunst des Fechtens. By completing the fencing manual of Antonius Rast, Mair gave us valuable insight into the Nuremberg fencing tradition; his own works are impressive on both an artistic and practical level, and his extensive commentary on the uncaptioned treatises in his collection serves to make potentially useful training aids out of what would otherwise be mere curiosities. Finally, in gathering so many important fencing treatises he succeeded in preserving them for future generations; they were purchased by the fabulously wealthy Fugger family after his death and remain in Augsburg to this day.

Contents

- 1 Treatise

- 1.1 Manuscripts

- 1.2 Books

- 1.3 Personal Compendiums

- 1.4 Preface

- 1.5 Register

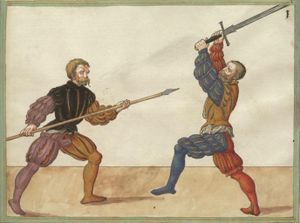

- 1.6 Longsword

- 1.7 Dussack

- 1.8 Short Staff

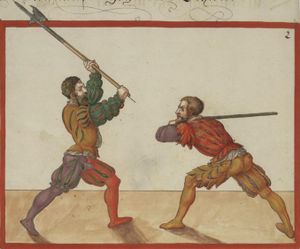

- 1.9 Long Staff

- 1.10 Halberd

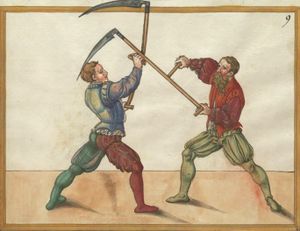

- 1.11 Scythe

- 1.12 Flail

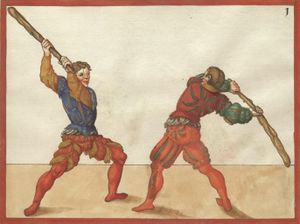

- 1.13 Peasant Staff

- 1.14 Mixed Weapons

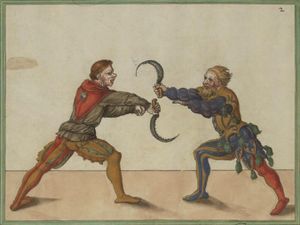

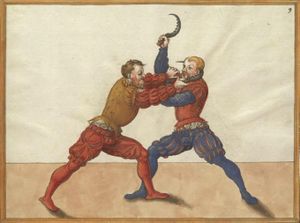

- 1.15 Sickle

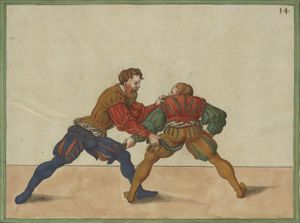

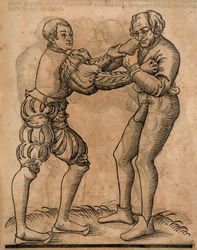

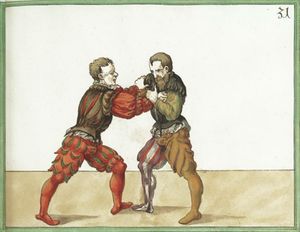

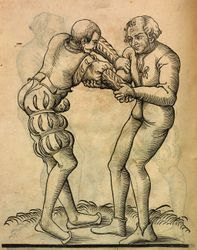

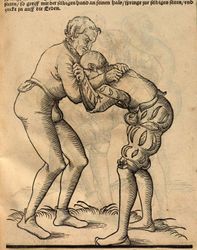

- 1.16 Grappling

- 1.17 Dagger

- 1.18 Side Sword

- 1.19 Side Sword and Dagger

- 1.20 Side Sword and Buckler

- 1.21 Poleaxe

- 1.22 Longshield

- 1.23 Armored Fencing

- 1.24 Foot vs. Horse

- 1.25 Mounted Fencing

- 1.26 Copyright and License Summary

- 2 Additional Resources

- 3 References

Treatise

In addition to the three manuscripts that Mair personally commissioned (detailed below), Mair is known to have collected the following during his life:

Manuscripts

- Codex I.6.2º.1 - A copy of one of Hans Talhoffer's fencing manuals, possibly the MS XIX.17-3.

- Codex I.6.2º.2 - A compilation of Jörg Wilhalm Hutter's longsword treatise and Lienhart Sollinger's manuscript reproduction of Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterey.

- Codex I.6.2º.3 - A copy of Codex I.6.4º.5 with descriptive text by Hutter.

- Codex I.6.2º.4 - Jörg Breu's draftbook for his work on Mair's treatises.

- Codex I.6.2º.5 - A compilation of Hans Medel's revision of Sigmund Schining ein Ringeck's treatise, Medel's own writings, fencing prints by Maarten van Heemskerck, and records of the Marxbrüder fencing guild.

- Codex I.6.4º.2 - A compilation of two treatises from the Nuremberg Group and a much older, uncaptioned series of fencing drawings known as pseudo-Gladiatoria.

- Codex I.6.4º.3 - A compilation of several treatises from the tradition of Johannes Liechtenauer, possibly compiled by Jud Lew. (Not verified as being in his collection.)

- Codex I.6.4º.5 - Jörg Wilhalm Hutter's draftbook.

- MS E.1939.65.354 - Gregor Erhart's fencing manual. (Formerly Codex I.6.4º.4.)

- Reichsstadt "Schätze" Nr. 82 - The expanded and finished version of Antonius Rast's fencing notes.

Books

- Der Altenn Fechter anfengliche kunst, compiled by Christian Egenolff

- Opera Nova by Achille Marozzo

- Ringer Kunst by Fabian von Auerswald

Personal Compendiums

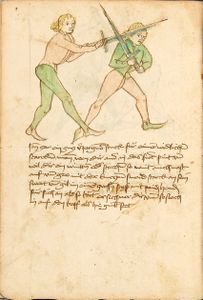

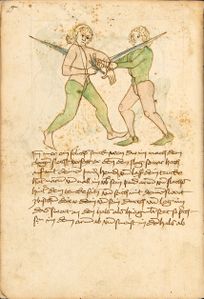

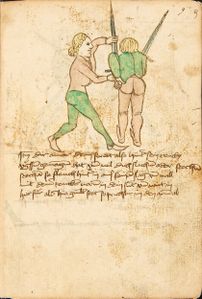

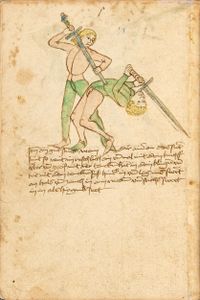

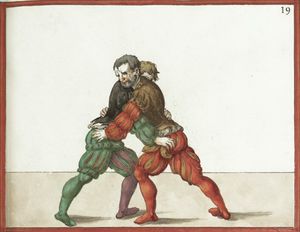

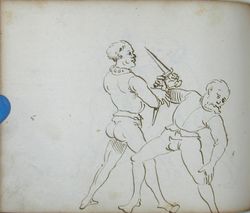

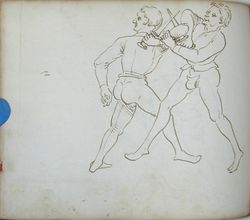

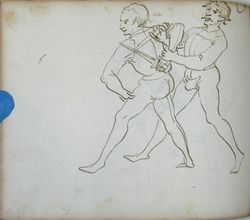

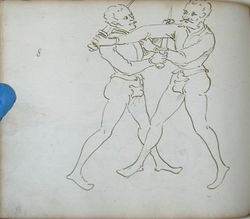

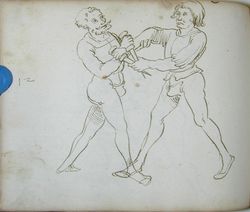

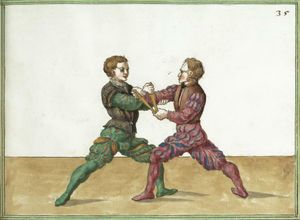

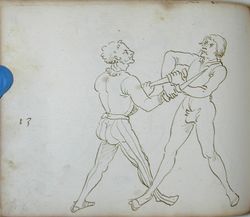

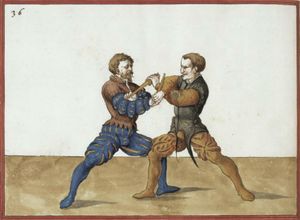

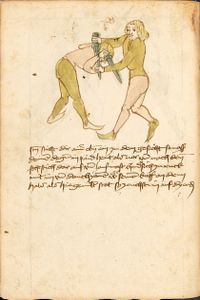

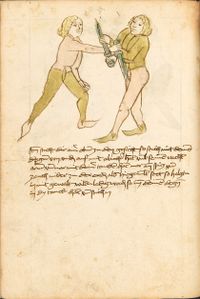

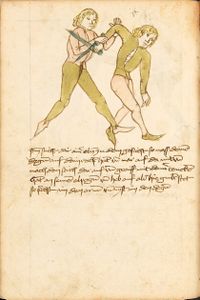

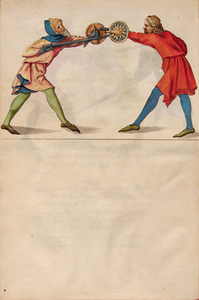

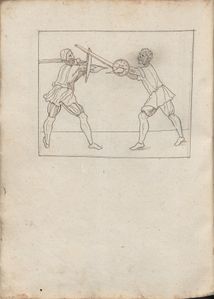

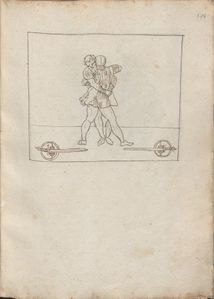

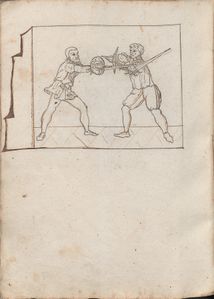

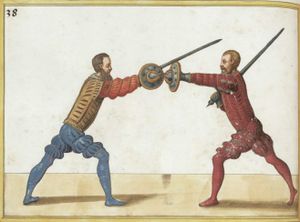

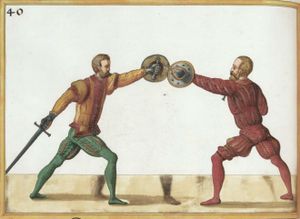

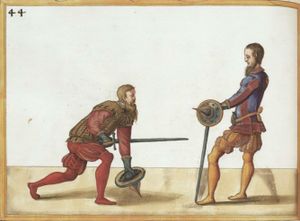

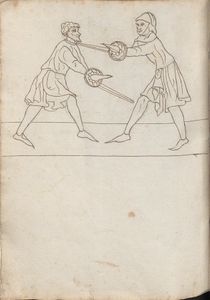

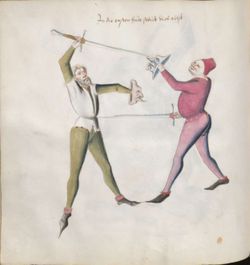

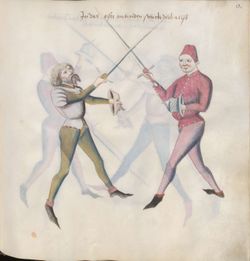

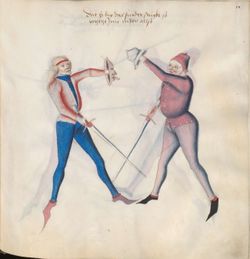

Much of Mair's content represents his revision and expansion of the older treatises listed above, including adding descriptive content to uncaptioned images. Where available, these images are displayed for in the left-most column, labeled "Source Images", for comparison purposes. Mair's own illustrations appear in the second image column.

Source Images |

Images |

Dresden I Transcription (1540s) |

Vienna I Transcription [German] (1550s) |

Vienna I Transcription [Latin] (1550s) |

Munich I Transcription (1540s) |

Draftbook Transcription (1540s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The First Part of the Fechtbuch |

[001r] Der Erst Tail diß Fechtbuch |

[005*r] Vorred in das Fechtbuch. |

|||||

|

Preface It would only be right and proper, and I would have thought it good and advisable, for me to publish this knightly book of honour without any preface, as to the knowledgeable each art can with good reason defend and speak for itself. But as I become aware and notice, that this manly art of fencing, as other arts besides, which profit the beloved fatherland as useful and honourable, and by the learned are praised for men to study, are by those who out of idleness and neglect fail to respect the good virtues and arts, and those that do neither love nor feel inclination to learn, not just failing to support, but the same that from an ignorant, impertinent and lazy carelessness use disdainful words of mockery to besmirch them (as I during the long time during which I have compiled this work of honour, myself had to experience, and such things did often have to hear to my vexation). Therefore, moved and instigated against my will that I would order and place here a little preface and apology of the noble knightly art of fencing, to all beloved honourable men, be they of noble birth or otherwise. To this end I would not look on the cost, just as I did not with the other work and zeal that I put into this work, with unwavering hope that this preface would succeed to serve as good and comprehensible instruction for the reader. |

[002r] Vorred Es were wol recht vnnd billich Vnnd hette mich auch fur guet vnnd Ratsam angesehen · Das ich dises Ritterlich Eernbuch · dieweil sich Jede kunst · beÿ allen verstenndigen · mit gutem grund selbs verthedingen vnnd versprechen kan · on alle vorred von mir außgeen lassen · sollte · Dieweil ich aber merckh · sihe vnnd briefe · das dise manliche Kunst des Fechten · wie annder kunsten mer· so dem geliebten Vatterlannd als fur nutzlich vnnd Eerlich · den mentschen durch die gelerten geprisen vnd zulernen furgestellt sein· von den Ihenigen · so auß faulkait vnnd hinlessigkait · der guten tugenden vnnd kunsten nicht achten · auch dieselben zulernen kain liebe noch naigung nicht allain nit tragen · sonder dieselben vil mer auß vnwissender frechen faulen leichtuertigkait · mit verachtlichen schmachworten · besudlen vnnd belegen ( · wie ich dann die lannge zeit · als ich dises Eernnwerckh zusamen geordnet · selbs erfaren · vnnd solches offtermalen mit verdruß hab hören muessen · ) Derhalben ich wider meinnen willen verursacht vnnd bewegt worden · das ich der Edlen Ritterlichen kunst des Fechtens vnnd allen geliebten Eerlichen vom Adel vnnd sunst · so sich der manlichen Kunst · dem Eerliebenden Vatterlannd zu Eern · nutz vnnd wolfart gebrauchen · ein klaine Vorred vnnd verthedigung vorher hab setzen vnnd ordnen wellen Daran mich auch neben annderer muhe vnnd arbait · so ich auf dises werckh gelegt · der vncost gar nicht betauren soll ungezweifleter hoffnung · das dise Vorrede dem leser zu gutem verstenndigem bericht raichen vnnd gedeichen werde / · |

[006*r] Vorred. Es were nur recht und billich, und hette mich auch für gut und ratsam angesehsen, Das Ich dises ritterliche Eerenbuch, Dieweil sich jede kunst bey allen verstendigen, mit gutem grundt selbst vertheidigen und versprechen kan, on alle vorred, von mir aussgeen lassen solte. Dieweil ich aber merck, sihe und briefe, das dise manliche kunst des fechten, wie ander künsten mer, so dem geliebten vatterland, als für nutzliche und eerliche, den menschen durch die gelerten geprisen, und zu lernen furgestalt sein, von denjhenigen, so aus faulkait und hinlessigkait, der gutten tugenden und kunsten nicht achten, auch dieselben zu lernen kain liebe noch naigung, nicht allain nit tragen, sondern dieselben vilmer aus unwissender frechen, faulen leichtvertigkait, mit verachtlichen schmachworten, besudeln, und belegen (wie ich dann die lange zeit, als ich dises Eerenwerck zusamen geordnet, selbst erfahren, und solches offtermalen mit verdruss hab horen mussen) Derhalben ich wider meinen willen verursacht und bewegt worden, das ich der Edlen ritterlichen kunst des fechtens, und allen gelibten Eerlichen vom adel und sonst, so sich der manlichen kunst, dem Eerliebenden vatterland zu eeren, nutz und wolfart gebrauchen, ein klaine vorred und vertheidigung vorher hab setzen und ordnen wollen. Daran mich auch neben anderer muse und arbait, so ich auf dises werck gelegt, der unkost gar nicht beschauen soll, Ongezweiffelter hoffnung, das dise vorredt, dem leser zu gutem verstandigen bericht reichen und gedeihen werde. |

|||||

|

The ancient and modern Greek, Latin and German historians have put much zeal and effort into the question, in numerous points and articles, from which basis and causes, in which time, and in what land and situation, and by whose instigation, the knightly sport of fencing first took its origin and source, but in the cause and the tale of years, or in place and situation, they all are in agreement, that this knightly art of fencing was in the beginning established with the purpose of serving to the honour, virtue and stimulation to the youth of both high and low birth, and also to the protection and preservation of the fatherland. But in the question of naming who was the first inventor of this art, they are found somewhat discordant and of differing opinions. |

Es haben sich die alten vnnd Newen Griechischen / Lateinischen vnnd Deutschen Historici · ob dem Ritterspil des Fechtens · Inn etlichen puncten vnnd Articulen Namlich auß was grund vnnd vrsachen · auch zu welcher zeit · Inn was Lannd vnnd gelegenhait vnd auch durch wen sie anfengcklich Jren vrsprung empfanngen · vnnd hergeflossen seÿe · seer vast bemuehet · aber Inn der vrsach vnnd Jarzal · auch Ort vnnd gelegenhait sie alle vast vberain stimmendt · vnnd zugleich bekennen Das dise Ritterliche kunst des Fechtens · der Jugent von hochen vnnd Nidern stennden zu eernzucht vnnd anraitzung guter Mannlicher tugent · auch zu schutz vnnd erhalltung des Vatterlanndts · sampt aller Redlichkait Im anfanng gefundiert auch die zu lernen furgenomen worden seÿ Noch werden sÿ allain Inndem · welcher der erst erfinder diser Kunst zubenennen were · etwas mißhellig vnd vngleicher mainung befunden · |

Es haben sich die alten und neuen Griechischen, Lateinischen und Teutschen historici, ob dem ritterspil des fechtens, in etlichen puncten und articulen, menlich aus mass grund und ursachen, auch zu welcher zeit, in was land und gelegenhait, und auch durch wen, sie anfanglich iren ursprung entpfangen, und hergeflossen sey, seer vast bemuehet, aber in der ursach und jartzal, auch ortt und gelegenhait, sie alle cast uberain stimmend, und zugleich bekommen, das dise ritterliche kunst des fechtens, der jugent von hohen und nidern standen, zu Eeren, zucht und anraitzung gutter manlicher tugend, auch zu schutz und erhaltung des vatterlands, sambt aller redlichkait, im anfang gefundiert, auch die zu lernen fürgenomen worden sey. Noch werden sie allain in dem, welcher der erst erfinder diser kunst zu benennen were ettwas misshellig und ungleicher meinung befunden. |

|||||

|

And while many of the learned say that this art of the knightly sport, as other arts beside, must have come among men to influence[?] their appetites and pleasure, from above, i.e. from God and celestial influence of the stars, as is well believable. Besides this, some say that Pollux, who was honoured by the Romans, was an instigator of this honourable art; others would attribute the honour of such invention to Mercury. But both these statements must be found somewhat obscure and uninstructive from the fact that they do not explain what use or profit they would have made from this art, or which lords they took as their disciples that would have learned the art from them and in turn passed it on. |

[002v] Vnnd wiewol etlich der Gelerten sagen das dise kunst des Ritterspils · wie annder kunsten mer Inn die mentschen zu kumen · seinen einflus · begird vnd lust · von oben herab · das ist von gott vnnd Himlischer Influentz · des Gestirens haben mueß · welchs dann auch wol zu glauben Hieneben sagen ainstails das Polux · welchen die Römer geeret haben · ein anfenger diser Eerlichen kunst gewesen seÿ · Anndere wo°llen solche erfindung vnnd Eher dem Mercurio zu aignen · Es werden aber baider anzaigung · auß der vrsach das nicht befunden wirt · was nutz vnd frucht sie Inn diser kunst geschafft · auch welch herren sie zu Schueler gehabt · die Kunst von Inen gelernet · vnd hinder Inen verlassen haben · etwas dunckel vnnd vnleerhafftig befunden · |

Und wiewol etlich der gelerten sagen, das dise kunst des ritterspils, wie andere künsten mer, unn die menschen zukomen, seinen einfluss, begird ud lust, von oben herab, das ist von Gott und himlischer inflyentz des Gestirns haben muess, malchs dann auch wol zu glauben, Hineben sagen ainsstails, das Polux, welchen die Römer geeret haben, ein anfenger diser Eerlichen kunst gewesen sey. Andere wollen solchen erfindung und eer, dem Mercurio zuaignen. Es werden aber beide antzeignung aus der ursach, das nicht befunden wirt, was nutz und frucht sie in diser kunst geschaft, auch welche herren sie zu schueler gehabt, die kunst von inen gelernet und hinder inen verlassen haben, etwas tunckel und unlerhafftig befunden. |

|||||

|

But the majority of the same historiographers state and testify that Probas, the famous fencer and teacher of Theseus, the king of Athens in Greece, in which realm the knightly art in the beginning and for a long time thereafter did much prosper, was the first inventor and establisher of this art. For this same Probas did to the highest extent praise and commend the knightly exercise to king Theseus with fair and rigorous argument, to the kingdom and fatherland, to all ordered conduct and honesty, and all that serves the preservation of the liberty of the fatherland, as a highly expedient medicine against the useless, inert and recreant slothfulness and other frivolity. Which instruction said king Theseus took to heart and in consideration of that this knightly art and exercise of fencing in times of peace may be an honourable and manly exercise for the young, but in times of distress and danger may serve and succeed towards the fatherland's honour, advantage and prosperity, he put belief in Probas and himself together with some of the most noble of his court, undertook it to learn this knightly art of fencing, to which end Probas was highly assiduous. And thus the honourable art of fencing prospered from the cause that each [practitioner] was found that much more competent and able to support the fatherland in its need. Said king Theseus did build, to considerable cost, many sumptuous houses dedicated for the exercise of this art, in Athens and elsewhere in his realm, which was the beginning of the general [systematic] tuition in fencing. These events under the reign of the Athenian king Theseus, who according to the reckoning of the Urspergian[3] reigned for thirty years, took place and occurred approximately in the year 1224 before the birth of our saviour Jesus Christ, and from this circumstance it follows that this art, which has been founded by kings, and by many of royal and noble kin and blood besides, which served to themselves as a noble exercise and towards honour, advantage and necessity for the fatherland, may well and truly be called a noble and knightly sport. |

Aber der merertail Derselben Historiographeÿ sagen vnd zeugen · das Probas · welcher beruempter Fechter · vnnd ain lermaister Teseÿ · des Kunigs zu Athen Inn Griechenlannd · Inn welchem Reÿch die Ritterliche kunst Im anfanng · vnnd lannge zeit hernach vast · geplueet hat · gewesen ist · der erst erfinder vnnd aufrichter diser Kunst gewesen seÿ · Dann diser Probas die Ritterliche übung dem Kunig Teseÿ · mit so scho°nen grundtlichen Argumenten · dem Kunigreich vnnd Vatterlannd · auch allem ordenlichem wesen vnnd redlichkait · sampt allem was zu erhaltung der Freÿhait des Vatterlannds diennet · als ain hoch nutzliche Artzneÿ wider die vnutzen hinlessige faige faulkait · vnnd anndrer leichtuertigkait · zu dem ho°chsten geprisen · vnnd gelobet welches bemellter Kunig Teseus zu hertzen gefiert · vnnd hat Inn bedennckung · das dise Ritterliche Kunst vnnd übung des Fechtens · zu fridlichen zeiten der Jugent ein Eerliche vnnd manliche vbung seÿe Vnnd aber Inn der nott vnnd geferlichkait dem Vatterlannd zu ehrn · nutz vnnd wolfart raichen vnnd gedeihen mo°g · dem Probas · glauben geben vnnd darauf selbs · sampt etlichen der seinen vom hof des po°sten Adels · dise Ritterliche kunst des Fechtens zulernen vnnderstannden · Inn welchem Probas · hochbeflissen gewesen · Vnnd hat sich also die Eerliche Kunst des Fechtens · auß vrsachen das Jeder dem Vatterlannd · Inn der not zu helffen · dester Kunnder vnnd geschickter befunden wurd dermassen so vast zugenomen · Das bemelter Kunig Teseus · etliche ko°stliche heuser zu der übung diser Kunst · zu Athen vnnd annderstwo Inn seinem Reich · nicht mit wenigem uncosten · reichlich gebawen hat · Welches dann ein anfanng der lernung des Fechtens Inn gemain gewesen ist · Es haben sich aber dise ding beÿ dem zehenden Kunig [003r] der Athenienser Teseus genannt Welcher nach der Rechnung Vrspergensis 30 · Jar · geregiert · vngeuarlich Anno · 1224 · vor der geburt vnnsers hailannds Jhesu Christi · sich zugetragen · vnnd verloffen · vnnd von dannen her dise kunst · weliche die Kunig fundiert vnnd noch vil von Kunigelichem vnnd Furstlichem geschlecht vnnd gebluet · dasselbig Inen selbs zu ainner Adenlichen Vbung · dem vatterland zu Eern nutz vnnd notturfft geprauchen · auch billich ein Adelichs Ritterspil warhafftig genent werden mag · / |

Aber der merentail derselben Historiographi, sagen und zeugen, das Probas, welcher berumbter fechter und lermaister Teseii des kunigs zu Athen in Griechenland in welchem raich die ritterliche kunst im anfang, und lange zeit hernach, vest geplüt hat, gewesen ist, der erst erfinder und aufrichter diser kunst gewesen sey. Dan diser Probas die ritterliche übung dem künig Teseii mit so schönen grüntlichen argumenten dem künigreich und vatterland auch allem ordentlichen wesen und redlichkeit, sambt allem was zu erhaltung der freiheit des vatterlands dienet, als ain hoch nützliche artzney wider die unnützen hinlessige faige faulhaitt [006*v] und andere liechtvertigkait, zu dem höchsten gebrisen und gelobet. Welches beelter kunig Teseus zu hertzen gefiert, und hat in bedenckung das dise ritterliche kunst und übung des fechtens zu fridlichen zeiten der jugent ein Eerliche und manliche ubung seye und aber in der not und geferlichkait dem vatterland zu eeren nutz und wolfart raichen und gedeihen mag, dem Probas glauben geben, und darauf selbs sambt etlichen der seinen vom hof des besten Adels, dise ritterliche kunst des fechtens zu lernen understanden, in welchem Probas hochbeflissen gewesen. Und hat sich also die Eerliche kunst des fechtens, ausz ursachen, das jeder dem vatterland, in der not zuhelffen dester künder und geschickter befunden wurd, dermassen so vast zugenomen. Das bemelter künig Teseus, etliche köstliche heuser zu der übung diser kunst, zu Athen und anderstwo in seinem Reich, nicht mit wenigen unkosten, reichlich gebauen hat. Welch dann ein anfang der lernung des fechtens in gemain gewesen ist. Es haben sich aber dise ding bey dem zehanden kunig der Athenienser Teseus genant, welcher nach der rechnung Ursperpensis, dreissig jar geregiert, ungefärlich anno .1224. vor der geburt unsers heilands Jhesu Christi, sich zugetragen und verlauffen, und von dannenher dise kunst welche die künig fundiert, und noch vil von küniglichen und fürstlichen geschlecht und gebluet, dasselbig inen selbst zu einer Adelichen übung, dem vatterland zu Eeren nutz und notturfft gebrauchen, auch billich ein Adeliges ritterpil warhafftig genent werden mag. |

|||||

|

But what zeal and considerable cost was invested by the ancients in the knightly art of fencing, and in what earnest and honourable reputation its exercise was held, furthermore what high persons undertook to learn this art, and to what good consequence this art served in all lands and kingdoms, this I will also tell and describe. |

Was aber fur fleÿs Vnnd Reichlicher vncosten von den alten auf dise Ritterliche Kunst des Fechtens gelegt · auch mit was ernst · vnnd Eerlichem ansehen dise übung gehalten worden · zudem was fur hohe personnen sich diser kunst zulernen vnnderfangen · vnd das auch dise Kunst allen Lannden vnnd Kunigreichen zu gutem geraicht habe · will ich auch erzelen vnd beschreiben · |

Was aber für fleis und reichlicher unkosten von den alten, auf die ritterliche kunst des fechtens gelegt, auch mit was ernst, und eerlichem ansehen die übung gehalten worden, zudem was für hohe personen sich diser kunst zu lernen underfangen, und das auch dise kunst allen landen und künigreichen zu zu gutem gewirckt haben, will ich auch erzelen und beschreiben. |

|||||

|

Because the human nature of budding youth may not rest or be idle, and because this knightly exercise as a manly virtue was well praised and held in high honour, not alone in Greece but all over the world, thus in the land of Greece, and in other places besides, and especially in the province of Boeotia, by the strong and widely famous fencing master Cercioni, places and sites were chosen and cleared where one could fence, wrestle, duel and practice other knightly games, which were given by him the name of Palestra, which name is still in use by the Latins. This example was followed by the mighty cities, such as Athens, Argis, Sparta, Corinth, and other peoples besides, which in the interest of beloved brevity I will refrain from describing. After the knightly art made entrance in Italy, the Romans with unspeakable cost very great and artful houses were constructed and called Theatrum, that is "show-houses", and the prize among these was attained by the Roman Consul Staurus, who built such an artful Theatrum, which stood on three hundred and sixty marble pillars, and full hundred fencers might therein fence, in honour of the god Jupiter. In these show-houses the fencing-masters would at appropriate times, specifically on holidays, assemble and hold such exercise of the knightly sport, dedicated to the honour of the gods, in the exercise of fencing, wrestling, running, both on horse and on foot. The exercise of fencing was also performed with such honourable and respectable virtuous order, that sessiones were held and introduced in which everyone, i.e. providing he was of nobility, or held an office of state, could sit and watch the knightly sport. That the Roman people loved the knightly sport to such an extent, and was assiduous to learn and visit it, that they once in such great number came to the Theatrum and show-houses, that these, in spite of being built with art and strength, could not endure such zest of the population that, as Livius writes, at Fidena such a house due to the great weight did collapse and fell to the ground, killing two thousand men.[4] Even in the current day, in many places such former and collapsed show-houses can be seen in Greece, Italy and Lombardy, especially in Rome and in Verona. |

Nachdem die mentschliche Nattur Inn der plueende Jugent nicht ruwen · oder feiren kan · Vnnd aber dise Ritterliche übung · als ain manliche tugendt nicht allain Inn · Grecia · sonnder Inn aller weelt größlich gelobt · vnnd Inn hochen Eern gehallten ward Do wurden Inn den lannden Grecia · vnnd anndern orten mer · vnnd besonders Inn der Lanndtschafft Boecia von dem starcken vnnd weit beruembten Fechtmaister Cercioni [003v] platz vnnd ort · darauf man Fechten Ringen Kempffen vnnd annder Ritterspil üben sollt erwelt vnnd gefreiet · die den namen Palestra · von Im empfanngen · vnd des die Lateiner noch zunennen Im geprauch haben · Dennen haben nachgeuolget · die gewaltigen Stet als Athen · Argis · Sparta · Corinthon · vnnd anndere völcker mer · die ich vmb geliebter kurtze willen · zu beschreiben vnderlassen · will Nachdem aber die Ritterliche Kunst Inn Italian eingetreten · seind von den Römern gar kunstliche grosse heuser · mit vnseglichem vncosten · Reichlich erbawet · vnnd · Theatrum · das ist Schawheuser genannt worden · vnnder welchen erbawungen · der Römisch Consul Staurus · welcher ein solichen kunstlichen Theatrum · der auf · 360 · Marbelstainen seulen stunde · vnnd hundert bar fechter darInnen Fechten mochten · dem Gott Jouis zu eern erbawet · den preis erlannget hat Inn welchen Schawheusern dann die Fechtmaister zu bequemblicher zeit · vnnd sonderlich an den Festtägen · darauf dann soliche übung des Ritterspils · den Go°ttern zu ehern gestifftet was · zusamen kamen · vnnd alsda Ir vbung des Fechtens Ringens lauffens · baides zu Roß vnnd fuoß hielten · Es wurden auch der vbung des Fechtens · mit so ainer Eerlichen ansehlichen züchtigen Ordnung zugesehen · das Sessiones · wohin Ieder dem Ritterspil zuzesehen . Namlich · nachdem er geadlet · oder Inn des Rats Ämbtern gewesen · sitzen sollt · gemacht vnnd geordnet wurden · dann das Römisch volckh diß Ritterspil dermassen geliebt vnnd das zulernen vnnd zubesuechen · so hoch beflissen gewesen das sÿ etwann mit so grosser anzal Inn die Theatrum · vnnd Schawheuser zusamen · kumen das die gemellte gebew · unangesehen · das sie von kunst vnd sterck so fleissig gemacht · solchen last des volckhs · nicht hat ertragen mo°gen Vnnd wie Liuius schreibt das zu Fidena · ein solch haus · von wegen des grossen lasts ernider ganngen · zu boden gefallen · vnnd ob · 2000 · · Mentschen · erschlagen hab Es werden aber noch heutigstags an vil orten · solche anzaigung der verganngne vnnd zerfalne Schawheuser Inn Griechen · Italia vnnd Lombardia · vil gesehen vnnd Innsonders zu Rom vnd Diethrichs Bern noch heutigstags · gute anzaigung von sich geben · |

Nachdem die menschliche Natur der plüende jugend nicht ruwen, odere feiren kan unnd aber dise ritterliche übung als ain manliche tugend, nicht allain in Grecia, sondern in aller Welt, grosslich gelobt, und in hohen eeren gehalten ward, So wurden in den Landen Grecie, und andern orten mere und besonders in der Landschaft Boecia, von dem starcken und weitberumbten fechtmeister Cercioni, plätz und ort, darauf man fechten, ringen, kampggen, und andere ritterspil üben solt, erwelt und gefreiet, die den namen Palestra von im empfangen, und dass die Lateiner noch zunennen im gebrauch haben. Denen haben nachgevolget die gewaltigen stet, Als Athen, Argis, Sparta, Corinthon, und andere Volcker mer, die ich umb geliebter kurtze willen zubeschreiben underlassen will. Nachdem aber die ritterliche kunst in Italia eingetretten, sind von den Römern gar künstliche grosse heuser, mit unseglichen kosten, wirklich erbauet, und Theatrum, das ist Schauheuser genant worden, under welchen verbauungen, der römisch Consul Staurus, welcher ein sollichen künstlichen Theatrum, der auff dreihundert und sechtzig marmolstainen seulen stunde, und hundert bar fechter darinnen fechten mochten, dem Got Jovis zu eeren erbauett, den preis erlanget hat. In welchen schauheusern dann die fechtmaister zu bequemlicher zeit, und sonderlich an den festtagen, darauff dann sollche übung des ritterspils, den Göttern zu eeren gestifftet war, zusamen kamen, und alda in übung des fechtens, ringens, lauffens, baides zu ross und fuss, hielten. Es wurde auch der übung des fechtens mit so einer eerlich ansehlichen züchtigen ordnung zugeschen, das sessiones, wohin jeder dem ritterspil zugesehen, namlich nach dem eer geadelt, oder in des rats ämbteren gewesen, sitzen solt, gemacht und geordnet wurden. Dann das römisch volck disen ritterspil dermasen geliebt und das zulernen und zubesuchen, so hochbeflissen gewesen, das sie ettwan mit so grosser antzal inn die Theatrum und schaufhauser zusamen kamen, das die bemelte geben unangesehen das sie [007*r] von kunst und sterck so fleissig gemacht solchen lust des volcks nicht haben ertragen mugenn, und wie Livius schreibt, das zu Fidena ein solch haus von wegen des grossen lasts, ernider gang zu boden gefallen, und ob zwaitausent menschen erschlagen hab. Es werden aber noch heuttigen tags an vil orten solche antzaignung der vergangene und zerfalne scheuhauser in Griechen, Italia, und Lombardia, vil gesehen, und insonders zu Rom und Diettrichs Bern noch heuttigentags gute antzaignung von sich geben. |

|||||

|

Above we have heard how this knightly art of manhood was afforded and established by the learned and wise, also by the kings and princes as leaders of lands and kingdoms, which was done for the reason that land and people, widows and orphans would be kept in peace, calm and liberty, protected and saved from tyrants. For this to have its perfect and prosperous success, the highest heads, i.e. kings, princes, consuls and senators, did themselves undertake, learn and practice this knightly art, so as to present an example and motivation for their subjects, and there would be a great number of high potentates, i.e. emperors, kings, princes and noblemen, to be named at this point, which I have foregone, particularly in the case of the Greeks, not to put too much of a burden on the kind reader, and only alone the most notable Romans will I most briefly introduce and describe as a testimonial on the topic. |

Zuuor ist gehört Wie das dise Ritterliche Kunst · der Mannlichkait · von den geleert verstenndigen auch von den Kunigen vnnd Fursten · als vorsteeher der lannden vnd Kunigreichen · selbes herfur gebracht · vnnd fundiert worden seÿ · welchs dann auß vrsachen · das Lannd vnnd Lewt · [004r] Witwen vnnd Waisen · beÿ friden · ruw · vnnd Freÿhaiten beleiben · vnnd vor den Tÿrannen · beschutzt vnnd errettet werden mögen · beschechen ist · Hat aber solchs seinnen volkumnen außganng fruchtbarlich haben söllen · so haben die höchsten ha°ubter · als Kunig · Fursten · Consules vnd Senatores · dise Ritterliche Kunst · selbs fur die hand nemmen · leernen · vnnd Inn das werckh pringen · vnnd damit also anndern Iren vnnderthanen · ein Exempel der anraitzung · von sich geben muessen · vnnd weren Inn disem faal der hochen Potentaten · als · Kaiser · Kunig · Fursten vnnd Herren · seer vil zubenennen · welchs Jch / auf das der guthertzig Leser nicht zuuil beschwert werde · Vnnd Innsonders der Griechen zumelden vnnderlassen · Aber allain die Namhafftigesten Römer · zu zeugknuß der sach · zudem kurtzisten einfiern vnd beschreiben will ·/· |

Zuvor ist gehört, Wie das dise ritterliche kunst der manlichkait, von den gelert verstendigen, auch von den künigen und fürsten, als vorsteer der landen und künigreichen, selbs herfürgebrachtt und fundiert worden sey, welchs dann aus ursachen das Land und leut, witwen und waisen bey friden, ruw, und freihaiten beleiben, und von den Tyrannen beschützt und errettet werden mugen, beschehen ist. Hat aber solchs seinen volkommen ausgang fruchtbarlich haben sollen, So habenn die höchsten häubten, als künig, fürste, Consules und Senatores, dise ritterliche kunst selbs für die hand nemen, lernen, und in das werck bringen, und damit also under anderen iren underthanen, ein Exempel der anraitzung von sich geben muessen, Und weren in disem fall der hohen potentaten, als kaiser, künig, färsten, und herren, seer vil zu benennen, welchs ich, auff das der guthertzig Leser nicht zuvil beschwert werde, und insonders der Griechen, zumelden underlassen, (aber allain die namhafftigsten Römer, zum zeugknus der sach, zu dem kürtzesten einfieren, und beschreiben will. |

|||||

|

Romulus, the first founder and lawmaker of the city of Rome, and king thereat, according to the description by Plutarch, did hold himself so praiseworthy and fairly by his strength, swiftness and art of fencing in the war against the Fidenates that the enemy was beaten and the name of Rome did receive much praise, profit and honour. |

Romulus. der erste Stiffter vnnd Gesatzgeber · der Stat Rom · vnd Kunig daselbst · hat sich nach beschreibung Plutarche · durch sein sterckh · geschwindigkait vnnd kunst des Fechttens · Im streit wider die Fidenates · so loblich vnnd Redlich gehallten · das die feind geschlagen vnd dardurch · dem Römischen namen grossers lob · Nutz vnnd Eer widerfaren ist / |

Romulus der erst stiffter und gesatzgeber der stat Rom, und künig daselbst, hat sich nach beschreibung Plutarchi, durch sein sterck, geschwindigkait und kunst des fechtens, im strait wider die Fidenates, so loblich und redlich gehalten, das die feind geschlagen, und dadurch dem römischen namen grosses lob, nutz und eer widerfaren ist. |

|||||

|

But that the worthy Romans did place their trust, hope and refuge in the knightly art of fencing even at the time of most dire need is testified by Julius Caesar himself, and by Crispus Palustinus and even by the entire worship of writers. |

Das aber die werden Römer ir vertrauen, hoffnung und zuflucht in die ritterlichen kunst dess fechtens, ja auch in der zeit der höchsten not gesetzt haben, bezeugt Julius Cesar selb, auch Crispus Palustinus,[5] und schier die gantz schar der Scribenten. |

||||||

|

The said Julius Caesar writes that as he undertook his quick march upon Rome, that Pompey was in such need to flee Rome and so fearful that he did call to him and exhort the masters of the knightly art of fencing together with their school disciples and their family for his protection and led them away with him. With this masterful move Pompey did imagine that he had create for himself a double profit, firstly by keeping around him valiant persons experienced in such knightly art and secondly that he by this would vex Julius his enemy by reducing, breaking and divesting him of his strength and support. |

Bemelter Julius Cesar schreibt, als er seinen schnellen zug auf Rom furgenommen, das dem Pompeio so notig von Rom zu fliehen, auch so furchtsam gewesen, das Er die maister der ritterlichen kunst des fechtens, sambt irer schul discipel und geschlechter in die vil beruefft, auffgemanet, und zu seinem beschutz, mit im hinweg gefuert hab. Mit herllichem stuck pompaiens vermainet, ime zwen nütz geschaffet haben, Erstlich, das er mit sollichen ritterlich kunst, erfarene tapffere personen bey ime behalten, und damit desterbass benarrt wurde, fur das ander, das dem Julio seinem feind, sein sterck und hilff geringert, zerbrochen und entzogen wurde. |

||||||

|

Likewise the Roman senator Palustrinus writes on the Roman insurgence and rabblement of Catilinus that the most famous prince of all orators, Cicero, at the time Roman mayor and keeper of the city of Rome, upon whom the entire senate of the city of Rome laid the burden of the Roman public interest so that the city would not take ruinous damage by the impudent rabblement of Catilinus, among other prudent actions did order to assemble all valiant and honest masters of the sword, and their associated families and disciples, who in all weapons had learned, been instructed and exercised in how to use them to full advantage, not just in the city of Rome but also in Capua and other cities of Italy, which thereafter did receive the Roman freedom, so that they in the most dire need of the city of Rome did handsomely perform the most urgent office of the night-watch, which council the worthy Romans took in this and in similar pernicious riots, so that the noble Romans did ever and always hold this knightly art in highest honour so that they might rely on the same in times of acute need, from which their might, power and glory did increase daily.[6] |

Dessgleichen schreibt der römisch senatore Palustinus in der römischen aufrur und rottierung Catalini auch, das der hochberuembt fürst aller Oratores Cicero, diser zeit römischer Burgermaister und erhalter der stat Rom, Als im von dem gantzen senat der stat Rom, auff das die stat von der frechen Rottierung Catalini nicht verderblichen schaden empfinge, die gantz bürde des romischen gemainen nutz auferlegt worden, Welcher under anderen waisslichen furschungen geordert hat, namlich, das alle tapffer und redliche maister des schwerts, und derselben zugethanen geschlechter oder discipel, welliche in allen gewherenn mit allem vortail dieselben zugebrauchen gelert, underwisen, und geubt gewesen, nicht allain in der stat Rom, sonde zu Capua und allen andern stetten in Italian die sich dann der römischen freihait gebrauchen, zusamen beruffen, und denselben in solcher der stat Rom [007*v] höchster not, das allersorgklichest ambt, als die nacht schiltwacht, durch welliche alle rottirung leichtlich abgetriben werden mag, statlich beholfen hat, wellicher ratschlag dan werden Römern in diser und anderen dergleichen verderblichen auffruern, wol verschlossen hab, derhalben die Edlen Römer dise ritterliche kunst auff das sie derselben in der zeit furfallender nott gemessen mochten, je und allwegen hohen eeren gehalten, dadurch dann ir macht, gwalt und herrlichkait, taglich zugenomen. |

||||||

|

Julius, the first Roman emperor, did entrust his life to his body-guard, native Germans and famous fencers, more than four hundred in number, and to no-one else, and in Rome on the field of Mars he did himself fence, and did donate several treasures and prizes to the fencers shortly before his death. Likewise did emperor Augustus with great delight support and help the fencers, which example of love for the knightly art was freely followed by Tiberius the third Roman emperor, as is all recorded by Suetonius Tranquillus[7] and by others besides in their accounts. |

Julius · der erst Römische Kaiser · Hat seinnes Leibs Gwardia · so geboren Teutschen · vnnd beruembte Fechter · deren auch vber vierhundert gewesen · seinen leib allain · vnd sunst niemand annders vertrawen wo°llen vnnd zu Rom auf dem platz Marcio · selbs gefochten · auch etlich Clainat vnnd gewinnet er den Fechtern kurtzlich vor seinem Tod aufgeworffen · Deßgleichen · [004v] hat auch · Augustus · der Kaiser mit grössem Lust · selbs gethon · die Fechter angericht · darzu geholffen . vnnd zugesehen · welchem dann Tiberius der drit · Römisch Kaiser Inn liebe der Ritterlichen Kunst Reichlich nachgeuolget hat · welchs alles Suetonius Tranquillus vnnd annder mer Inn Iren beschreibungen melden · |

Julius der erst römisch kaiser, hat seines leibs guardia, so geboren Teutschen und beruembte fechter, davon auch uber vierhundert gewesen, seinen Leib allain, und sonst niemand anders vertrauen wollen, und zu Rom auff dem platz Marcio selbs gefochten, auch etliche Clainat unnd gewinnet er den fechtern kurtzlich vor seinem tod auffgeworffen. Deszgleichen hat auch Augustus der kaiser mit grossem lust selbs gethan. Die fechter angericht, dartzuo geholffen unnd zugesehen. Welchem dann Tiberius der dritt römisch kaiser in liebe der ritterlichen kunst reichlich nachgevolget hat, welches alles Suetonius Tranquillus und andere mer inn iren beschreibungen melden. |

|||||

|

The Romans were had the custom in spiritual matters of honouring the gods with this exercise of the knightly sport on their customary fest-days. In the month of March did they honourably hold a great feast lasting five days, of which three days of fencing for Pallas as a goddess of war. During these three days a special captain was designated who should instruct the youth in the upholding of manly honesty in fencing with all weapons twice daily, in the morning and in the evening. As the funeral of the body of Brutus should be held, his two sons Marcus and Decius did ordain abundant prizes and treasures for the fencers for which they should fence. Likewise as the emperor Probus won his victory against the Germans and did triumph he did let fence a total of three hundred[8] naked fencers in front of the public. |

Die Römer · hetten ein gewonhait das Sie Inn Gaistlichen sachen die Götter mit diser vbung des Ritterspils · auf gewonlichen Festtagen · vereereten · Im monat Martio · haben sie der Palladj · als ainner Göttin des Kriegs · ein gro°ß Fest namlich Funff tag lanng darunder dreÿ tag mit Fechten volbracht wurden · ganntz Eerlich gehallten · Inn welchen dreien tagen was ein besonderer Hauptman verordnet · der die Jugent zuerhaltung der manlichen redlichkait Im Fechten · Inn allen whoren zwaÿmal Im tag zu mörgens vnnd abents vnnderweisen sollt · als die leicht Brutj. vnnd sein begrebnuß beganngen werden sollt · haben seine zwen Sune Marcus · vnd Decius · den Fechtern gewinneter vnnd Clainnater · darumb zu Fechten reichlich verordnet · desselben gleichen · als · Probas · der Kaiser wider die Teutschen den sig erlanngt vnnd Triumphiert · hat er den Göttern zu Eern · neben anndern vierhundert bar Fechter · vor der gemaind Fechten lassen · |

Die römer hetten ein gewonhait das sie in gaistlichen sachen die Götter mit diser übung des Ritterspils auf gewonlichen festtagen vereereten. Im Monat Martio haben sie der Palladi als ainer Göttin des kriegs ein grosz fest nemlich fünff taglang darunder drey tag mit fechten volbracht wurden gantz eerlich gehalten. In welchen dreien tagen was ein besonderer haubtman verordnet, der die Jugent zu erhaltung der manlichen redlichkeit, im fechten mit allen wheren zwaymal im tag zumorgens und abends, underweisen solt. Als die leicht Bruti und sein begrabung begangen werden sollt haben seine zwen süne Marcus unnd Decius, den fechtern gewinneter unnd Clainater darumb zu fechten raichlich verordnet. Desselben gleichen als Probus der kaiser wider die Teutschen den sig erlangt unnd triumphiert, hat er den Göttern zu eeren neben anderen dreihundert bar fechter vor der gemaind fechten lassen. |

|||||

|

Likewise, Dominicanus by night and Gordianus at one time five hundred naked fencers, and after him emperor Philip the Arab, in a spectacle for the Roman people and in honour of his triumph did let fence a full thousand naked fencers on a single day.[9] Of such examples and histories would be many others to be told, but I feel that this should suffice for a general indication. |

Gleÿchsfals · Domicianus · etwann beÿ der Nacht · vnd Gordianus auf ein zeit Funffhundert Bar Fechter · vnnd hernaher Kaiser Philippus · der Arabier · Inn ainnem Schawspil · dem Römischen volckh vnnd seinem Triumph zu ehrn Tausent Bar Fechter · auf ain tag hat Fechten lassen · Deren Exempel · vnnd geschichte~ weren noch vil zuerzelen · aber mich bedunckt das dißmals zu ainer anzaigung gnug seÿ · |

Gleichfals Dominicanus etwann bey der nacht und Gordianus auff ein Zeit fünffhundert bar fechter, unnd hernach kaiser Philippus der Arabier, in einem schauspiel dem römischen volck und seinem Triumph zu eeren Tausent bar fechter auff einen tag hat fechten lassen. Deren Exempel unnd geschichten, weren noch vil zu erzelen, aber mich bedünckt das deszmals zu einer antzaigung genug sey. |

|||||

|

There was however in the beginning and during that time a different mindset in fencing, and as each judicious fencer may gauge for himself, the artful plays and hidden holds, steps and strikes may in origin not have been worked out as they have now, but over time, as the learned, whom I shall name below, also kings, princes and noblemen did dedicate themselves to the knightly exercise, by their assiduity were discovered the best artful plays and advantages with which a man might win in all tasks and cases of necessity, and this has gone on for such a time that in the end they were set down in epitomes or books, with figures and writing, so that one may still in this current day consult the experience of those ancients who did love the art. |

[005r] Es hat aber Im anfanng Vnnd zu diser zeit · ein anndere Mainung Inn dem Fechten gehabt · vnnd nachdem ein Jeder verstenndiger Fechter selbs ermessen kan · so haben die Kunstliche stuckh vnnd verborgne griff · trit vnnd straich Im anfanng nicht wie Jetzund · herfurgethan werden mögen · aber mit der Zeit · als sich die gelerten · die ich hernach benennen will · Auch die Kunig / Fursten vnnd herren · sich der Ritterlichen übung angenommen · alda seind die bösten Kunstlichsten stuckh vnnd vortail · damit der mann Inn allem thun vnnd faellen der nott · gewunnen werden möcht · durch Iren vleÿß herfurkumen · vnnd hat solches so lanng gewehret · das sie zuletst Inn Zettel oder Buecher · mit bossen vnnd schrifften · gebracht worden sein · als man dann beÿ den alten · so die Kunst geliebt noch heutigs tags · Inn der erfarung sihet · |

Es hat aber im anfang und zu diser zeit ein anderer meinung in dem fechten gehabt, und nach dem ein jeder verstandiger fechter selbs ermessen knn, so haben die künstliche stück und verborgene griff, tritt und straich, im anfang nicht wie jetzund, herfür gethan worden mugen, aber mit der zeit, als sich die gelerten, die ich hernach benennen will, auch die künig, fürsten unnd herren, sich der ritterlichen übung angenomen, alda seind die besten künstlichsten stück und vortail, damit der mann in allem thun und fällen der not, gewunnen werden möcht, durch iren fleis herfürkomen, und hat solches so lang geweret, das sie zuletzt in zettel oder büchern, mit bossen und schrifften, gebracht worden sein, als man dann bey den alten, so die kunst geliebt, noch heutigs tags in der erfarung sihet. |

|||||

|

In addition, the ancients, and especially the Greeks, did have such desire and love for the knightly exercise, that they did forego any kind of sweet food or drink several days before they would fence, likewise the lust of women besides all else that weakens the body and makes for heavy breathing, and did peruse such foods, as meat and other kinds, as do strengthen the body. On this matter did the learned medici, and especially the most famous Galen,[10] repeatedly and artfully discuss, whether austerity and abstinence or the practice of fencing would profit more for the life of man. Also Saint Paul does report such an example in his epistle where he says, you see that those who would fence and fight over a transient honour or treasure are wont to forego all lust, as if he would say, why do not you the same, as pious Christians who are fighting not for an earthly but for a heavenly honour in this world.[11] And therefore all those who love this knightly art do well to consider that in those times there were no drunken and immodest but sober, apt and most artful fencers. Also, it is rarely found in writing that among the ancients fencing was undertaken out of envy or hatred, as in our times regrettably occurs often, but out of love and artfulness. After the ancients did chastise themselves as they were expecting the day of fencing, they and the weapons with which they would fence were transported in all honesty on wagons to the fencing place or Theatrum, and for them the prizes and treasures were painted in fine likeness and carried before them, and also beforehand publicly posted on the market-place, and thus made known to the common man. This custom is attributed by the historiographers with great praise to Terentius Lucanus, who on three consecutive days did permanently have thirty naked fencers on the field, and when the fencers, masters and disciples entered the fencing place they put down their weapons in proper order (as is still the custom today); then the names of all fencers were written on pieces of paper and then with great assiduity the lot was drawn arbitrarily, and those two who were drawn by the lot then did have to fight most artfully and honourably for the treasure. For this, each of the fencers did most assiduously invoke their god, one Hercules, the other Mercury, yet others Pollux and Castor, and so forth, and pray that the lot would pair them with good and artful fencers, and not immodest ones who were not well experienced in the art. All of this does illustrate that the ancients did fence above all for art and knightly virtue and honour than for any other things, for which reason, for the later generations of fencers and for the honour of the knightly art, the fight-schools as they were held and the promenading houses and halls of the rich were painted in their likeness, and those who held them, and those who won the prize were finely depicted, and the highest prize in this was retained by the freedman of emperor Nero who at Antium at the great imperial palace and promenade did most artfully and gracefully depict the likeness of the fencing-schools and fencers.[12] |

Zudem haben die alten Unnd Innsonders die Griechen · ein solchen lust vnnd liebe der Ritterlichen vbung gehabt · das sie sich etlich tag zuuor emalen sie haben Fechten wo°llen · etlicher schleckhafftiger speiß vnnd getrannckh · auch vor dem wollust der weiber · sampt allem was den Leib schwecht vnnd schweren athem machet / enthallten, vnnd sich der speis · als flaisch vnnd annders so den leib sterckt/ gebraucht · Derhalben die gelerten · Medicj ·vnnd Innsunder der weitberuembt · Galenus · mermalen daruon Kunstlich disputiert haben · ob der abpruch vnnd abstinentz · oder die vbung des Fechtens · dem leben des Mentschens nutzer seÿe · Der hailig Paulus meldet solichs Exempels weis auch Inn seinner Epistel da er sagt Ir Sehent das sich alle die · welche vmb ein zeitlich zergenngckliche Eer vnnd klainat Fechten vnnd streiten wo°llen · sich von allem wollust enthallten · Als wollt er sagen · warumb nit Ir als fromen Christen · auch , die nit vmb ein Irdisch · sonder vmb ein Himlische Eer Inn diser wellt streitten ?? Vnnd haben derhalben alle liebhaber diser Ritterlichen Kunst · wol zugedenncken · das es diser Zeit nit volle trunckne · vnnd vnbeschaidne · sonnder nuechtere geschickte · vnnd ganntz Kunstliche Fechter geben hat · Man findt auch sellten Inn schrifften · das beÿ den vrallten auß neid vnd haß · sonder auß lieb vnnd Kunst gefochten worden seÿ als laider zu vnnser Zeit vil beschicht · Wann die alten sich gecastigeÿet vnnd also den tag des Fechtens erwartet haben Da hat man dann die Fechter mit Iren gewho°ren darInnen sie haben Fechten sollen · ganntz Eerlich auf we°gen zu dem Fechtplatz oder · Theatrum · gefuert · vnnd Inen die gewinneter vnnd Clainat fein abgemalt Conterfect · [005v] vorher getragen · auch solchs am marckt zuuor Angeschlagen dem gemainen man solches damit zu wissen gethon · Disen gebrauch geben die Historischreiber dem Terencio Lutano · welcher dreÿ tag nachainannder alweg dreÿssig bar Fechter auf dem platz zu fechten gehallten · mit grossem lob zu vnnd wann dann die Fechter · Maister vnnd Junger auf den Fechtplatz komen · haben sie dann die gewho°ren (· wie dann noch Im geprauch ist ·) nach ordnung nider gelegt · alß dann seind aller Fechter Namen auf zettelin von pappir geschriben worden · vnnd darnach das loß ganntz vngeuarlich mit höchsten vleÿß gehallten · Vnnd welche zwen dann mit dem loß heraus komen sein · haben dann vmb die klainat · ganntz kunstlich vnnd Eerlich Fechten muessen · Inndem haben die Fechter Jeder sein gott · ainner den Herculem · der annder den Mercurium · die anndern Polux · vnnd Castorem · vnd also furtan · mit höchstem fleyß angeruffen vnnd gebeten · das Inen gute kunstliche · vnnd nicht vnbeschaidne · die der Kunst nicht wol erfaren · Fechter · Im loß zugeschickt · vnnd beschert werden solt · Welchs dann alles ein anzaigung von sich gibet · Das die alten mer durch kunst · vnnd von · Ritterlicher Zucht vnnd Eern · dann vmb annderer sachen wegen gefochten haben · vmb disen willen den nachkomenden Fechtern · vnnd der Ritterlichen Kunst zu eern · die Fechtschuolen · wie die gehallten worden · an die Spacierheuser vnnd Sael der reichen Contrafectisch abgemalt · vnnd wer die gehalten · vnnd den preis erlangt · fein beschriben worden · seind · vnnder welchen der Libertus des Kaisers Neronis · welcher zu Ancio · an dem grossen Kaiserlichen pallast vnnd spacierhaus · die Fechtschuolen vnnd Fechter gar artlich vnnd zierlich hat abconterfecten lassen · den preiß behallten · |

[008*r] Zudem haben die alten, und insonders die Griechen, ein solchen lust und liebe zu der ritterlichen übung gehabt, das sie sich etlich tag zuvor, eemalen sie haben fechten wollen, etlicher schleckhaftiger speis und getranck, auch von dem wollust der weiber, sambt allem was den leib schwechet, und schweren athem machet, enthalten, und sich der speis, als flaisch und anders, so den leib sterckt, gebraucht. Derhalben die gelerten Medici, und insonder der weitberuembt Galenus, mermalen davon kunstlich disputiert haben, ob der abpruch und abstinentz, oder die übung des fechtens, dem leben das menschens nutzer seie. Der hailig Paulus meldet solchs Exempelsz wais auch in seiner Epistel da er sagt, ir sehent das sich alle die, welche umb ein zergengkliche Eer unnd Clainat, fechten und streitten wollen, sich von allem wollust enthalten, als wolt er sagen, warumb nit ir als fromme Christen auch, die nit umb ein irdisch, sonder umb ein himmlische eer in diser welt streitten ·/· Und haben derhalben alle liebhaber diser ritterlichen kunst, wol zugedencken, das es diser zeit nicht wolle truncken, und onbeschaiden, sonder nüchtern, geschickte, unnd gantz künstliche fechter geben hatt. Man findet auch selten in schrifften, das bey den uralten aus neid und hasz, sonder aus lieb unnd kunst, gefochten worden seig, als laider zu unser zeit viel beschihet. Wann die alten sich gekastigiret, und also den tag des fechtens erwartet haben, da hat man dann die fechter mit iren gewhören darinnen sie haben fechten sollen gantz eerlich auff wägen zu dem fechtplatz oder Theatrum, gefüert, und inen die gewinneter unnd Clainaten fein abgemalt Conterfect vorher getragen, auch solchs am markt zuvor angeschlagen, dem gemainen mann solchs damit zu wissen gethan. Disen gebrauch geben die historischreiber dem Terencio Lucano, welcher drey tag nacheinander allweg dreissig bar fechter auf dem platz zu fechten gehalten, mit grossem lob zu, und wann dann die fechter, maister und jünger auff den fechtplatz komen, haben sie dann die gewehren (.wie dann noch in gebrauch ist.) nach ordnung nidergelegt, alsz dann saind aller fechter namen auff zedelen von papir geschriben worden und darnach das losz gantz ongefarlich mit höchstem flais gehalten, uind welche zwen dann mit dem losz herausz komen sein, habend dann umb die klainat, gantz künstlich und eerlich fechten müessen. In dem haben die fechter ieder sein Gott, ainer den Herculem, der andere den Mercurium, die anderen Pollucem unnd Castorem, und also furtan, mit höchstem fleis angeruffen unnd gebetten, das iren gutte künstliche, und nicht onbeschaiden, die der kunst nit wol erfaren, fechter, in losz zugeschickt und beschert werden solt. Welchs dann alles ain antzaignung von sich gibt, das die alten mer durch kunst, und von ritterlicher zucht und eeren, dann umb andrer sachen wegen, gefochten haben, umb dessen willen den nachkomenden fechtern und der ritterlich kunst zu eeren, die fechtschulen wie die gehalten worden, and die spatzierhäuser und säl der reichen contrafectisch abgemalt, und wer die gehalten, und den preis erlangt, fein beschreiben wordenn seind, under welchen der Libertus des kaisers Neronis, welcher zu Ancio an dem grossen kaiserlichen pallast und spatzierhaus, die fechtschulen und fechter, gar artlich und zierlich, hat abconterfecten lassen, den preisz behalten. |

|||||

|

So did also the learned philosophers write about this knightly art, and the same were not ashamed to learn its, and among them Pythagoras, who was held a good fencer, was the foremost, as he did win the prize with his artful fencing at the celebration of the 48th Olympiad. Likewise did do many other excellent philosophers, without necessarily naming them all. So does Marcus Tullius Cicero, the Roman mayor and eventually administrator of the entire Roman empire write on the praise of fencing [T. q. folio.125.] I consider and trust entirely that nobody at all can be counted among the number of the learned orators who were not well versed and experienced in all arts that are knightly and even if we do not employ them in speaking, nor is it possible to discern this in us, if we are exercised in knightly sports, but the agility and the bearing of the body does concord and correspond with the agility of the voice, both in cheerful and in lamentable topics, such that it appears all the more agreeable to the listener. This is confirmed by the most learned orator Quintilianus who says that the persons who are given to praise and do not have contempt for the knightly sport of fencing and takes this as the cause that the same have great advantage and furtherance in the art of being well-spoken due to their agility Anacharsis[13] who lived at the time of king Croesus in Lydia, at the time when Rome had stood for 194 years, wrote that he did greatly marvel at how the Greeks were such stern judges while the fencers did bear themselves so heartily and well with[?] open spaces, houses, prizes, treasures and highest praise, as if he would say that the Greeks do well uphold the law and give to each man his due, to one his due praise and to the other his due punishment. Many more similar pronouncements furthering the honour of fencing could be mentioned, but as I feel that no amount would suffice for those who disparage this art, it should suffice for the present time. |

So haben sich auch die Geleerten Philosopi von diser Ritterliche Kunst zu schreiben vnnd dieselben selbs zulernen gar nicht geschemet · vnnder denen Pithagoras · den man fur ein guten Fechter gehabt hat · der erst gewesen sein soll · dann er an dem Fest der XLVIII Olympiadis · mit seinen kunstlichen Fechten · den preiß erlanngt hat · deßgeleichen vil anndere treffennlich Philosophi mer, on nott alle zumelden · gethan haben Marcus Tulius Cicero der Römisch Burgermaister vnnd etwann verwallter des gantzen Römischen Reichs · [006r] schreibet von dem lob des Fechtens also · Ich achte vnnd setze genntzlich · das niemand vnnd gar kainner Inn die zal der gelerten wolredner gerechnet werden soll · welcher nicht in allen kunsten · die den Rittermessigen zugeho°ren · abgericht · vnnd deren erfaren seind · vnnd ob wirs schon vnnder der Red · die nit gebrauchen · noch sicht man vnns solchs an · ob wir Inn Ritterlichen spilen geubt seinn oder nicht Dann die beweglichkait vnnd geberden · des leibs · sich mit der beweglichkait der stimm · In Frölichen oder kläglichen sachen Concordiern vnnd vergleichen · vnnd solches dem zuho°rer vil dester annemlicher erscheinet · Welches der Hochgelert Redner Quintilianus · bestettigt vnnd sagt · das die Personnen · so des Ritterspils des Fechtens sich gebrauchen · zu loben · vnnd gar nicht zuuerachten seien · vnnd setzt dessen vrsach · das dieselben zu der kunst der wolredenhait der beweglichkaithalben ein grossen vortail vnnd furdernus haben · Anarchus · der zu der Zeit Cresÿ · des Kunigs In Lidia · der Zeit als Rom · 194 · Jar gestannden · was · gelebt hat · schreibet · das In groß verwundere Dieweil die Griechen so trefflich Richter seien · vnnd darneben die Fechter · so einannder beschedigen · mit plaetzen · heusern · gewinneter clainnater · vnnd höchstem lob · so herrlich vnnd wol hallten · als wolte er sagen · Die Griechen halten gute Fecht · vnd erziechen Ir Jugent Inn aller manlicher Ritterlicher vbung · die zuerhalltung der Freÿhait diennet · vnnd geben Jedem was sich geburt · baide disem das lob · Jhenem die straff &c Dergleichen spruch so dem Fechten zu Eern furderlich seind · weren noch vil zu beschreiben · bedunckt mich auß vrsachen · das dem Lesterer diser kunst Nimmer guuegsam beschicht · auf dißmals · Inn disem faal gnug sein · |

So haben sich auch die gelerten philosophi von diser rittrerlich kunst zu schreiben, und dieselben selbs zu lernen, gar nicht geschemet, under denen Pithagoras, den man für ein gutten fechter gehabt hat, der erst gewesen sein soll, dann er an dem fest der XLVIII. Olympiadis, mitt seiner künstlichen fechten, den preis erlangt hat, deszgleichen vil andere treffliche philosophi mer, on not alle zumelden, gethan haben. Marcus Tullius Cicero der römisch bürgermaister unnd etwan verwalter des gantzen römischen reichs, scheibt von dem lob des fechtens also.T. q. folio.125. Ich achte unnd setze gentzlich, das niemand und gar kainer, in die zal der gelerten wolredner gerechnet werden soll, welcher nicht in allen künsten, die den rittermessigen zugehören, abgericht [008*v] unnd deren erfaren seind. Unnd ob wirs schon under der red die nit gebrauchen, noch sicht man uns solchs an, ob wir in ritterlich spilen geübt sein oder nicht, dann die beweglichkait und die geberden des leibs, sich mit der beweglichkait der stimm, in fröhlich oder cläglich sache, concordieren unnd vergleichen unnd solches dem zuhörer vil dester annemlicher scheinet. Welches der hochgelert redner Quintilianus bestettigt unnd sagt das die personen so des ritterspils des fechtens sich gebrauchen zu loben unnd gar nicht zu verachten seinen unnd setzt dessen ursach das dieselben zu der kunst der wolredenhait der beweglichkait halben ein grossen vortail unnd fürdernus haben. Anacharsis der zu der zeit Cresii des künigs in Lidia der zeit als Rom 194 jar gestannden was gelebt hat schreiben das in grosz verwundere dieweil die Griechen so strefflich richter seien unnd darneben die fechter so einander beschedigen nit plätzen, heusern, gewinneter, clainater, und hochstem lob, so herzlich und wol hallten als wolte er sagen die Griechen halten gute recht, unnd geben jedem was sich gebürt, baide disem das lob, jenem die straff ·/· Dergleichen sprüch so dem fechten zu eeren, fürderlich seind, weren noch vil zu beschreiben, bedünckt mich aus ursachen das dem lesterer diser kunst nimmer gnüegsam beschicht auf diszmals in disem fall gnug sein ·/· |

|||||

|

But before I proceed to the last portion, where I speak about the usefulness of the knightly sport, I cannot restrain myself from most briefly discussing the duel as the most warlike ornament of fencing, even though in this book for weighty reasons only little is contained on the topic of duelling. |

Aber ehemalen vnnd ich vonn · Dem letsten stuckh · das ist von dem nutz des Ritterspils etwas sage kan ich mich auß vrsachen · das der kampff als ein ernstliche zierd des Fechtens · wiewol von dem Kampff Inn disem Buch auß wichtigen vrsachen · wenig begriffen · mitnichten enthallten · sonder von demselben ein wenig· vnnd das auf das kurtzest zumelden mich vnndersahen · |

Aber eemalen unnd ich von dem letzten stück, das ist von dem nutz des ritterspils etwas sage, kan ich mich aus ursachen, das der kampff als ein ernstliche zierd des fechtens, wiewol von dem kampff in disem buch aus wichtigen ursachen, wenig begriffen, mit nichten enthalten, sonder von demselben ein wenig, unnd das auf das kürtzest zumelden, mich underfahen. |

|||||

|

The most learned doctor Johannes Aventinus[14] gives testimony in the first book of his chronicle that he made on the origin of the old and venerable house of Bavaria, that at the time of Jacob the patriarch, there was in Germany a king named Gampar or Kempfer,[15] who in the Saxon tongue, which is most similar to the German one, is known as king Gemper, from whom the word kampf ("duel") takes its origin, which the ancients, such as Homer, Orpheus, Ariostiphus, Diodorus, Siculus, and Strabo, besides many others beside, do clearly testify. This Gampar with his Germans made war on all of Asia, and filled it with his warlike name. From this the name of kampf or kempfer took its origin as a warlike deed But the abovementioned Aventinus says who did first make use of the duel, that even Hercules the son of Osir the king of the Egyptians, born from his spouse Isis, who is also called Ceres, did first bring the duel to German lands. There are also those who say that long before the Trojan War in Arcadia the duel was practiced by a native prince called Lycaon. But so that the kind reader may not be made confused or doubtful, he should know that this Lycaon lived long after both king Kampfer and Hercules. |

[006v] Der Hochgelert doctor · Johannes Auentinus · Zeuget Inn seinem ersten Buch · seiner Chronica · so er von dem herkomen des altloblichen haus zu Bairn gemacht hat · das zu der zeit Jacobs des Patriarchen · Inn Teutschlannden · ein Kunig Gampar · oder Kempffer · aber Sächsisch · welche sprach der Teutschen zungen am enlichisten zugemessen wirt · der Kunig · gemper · genannt wirt · dauon das wort Kempfen seinen vrsprung habe welche die alten · als Homerus · Orpheus· Ariostiphus · Diodorus · Siculus vnd Strabo · neben vil anndern mer · clärlich bezeugen · diser Gampar · hat mit seinen Teutschen das ganntz Asiam bekriegt · vnnd das mit seinnem ernstlichen Namen erfullet Daher der nam des kampff · oder kempffer als ainer ernstliche hanndlung · seinnen vrspru~g haben soll · wer aber sich des kampfs zu dem ersten gebraucht · sagt vorgemellter · Auentinus ·das In Hercules · der sun Osirs · des Kunigs der Egiptiern auß der Isidis die genannt wirt Ceres · seinem gemahel erborn · den kampff Inn Teutschlannden · erstlich gebracht habe · Es seind auch etlich die sagen · das lanng vor dem Troianischen krieg In Arcadia · von ainnem lanndsfursten · Licaon · genannt · der kampff gehallten worden seÿ · Damit aber der guethertzig Leser · Inn diser Rechnung nut Irr · oder Zweiffelhafftig gemacht werde · soll er wissen · das diser Licaon · lanng nach dem Kunig kampffer vnnd dem Hercule gelebt hat · |

Der hochgelert doctor Johannes Aventinus zeuget in seinem ersten buch seiner Chronica, so er von dem herkomen des altloblichen haus zu Baiern gemacht hat, das zu der zeit Jacobs des patriarchen in Teutschlanden, ein kunig Gampar oder Kempffer, aber sächsisch, welche sprach der Teutschen zungen am enlichsten zugemessen wirt, der kunig Gemper genant wird, davon das wort kampff seinen ursprung habe, welches die alten, als Homerus, Orpheus, Ariostiphus, Diodorus, Siculus, und Strabo neben vil anderen mer, clärlich bezeugen. Diser Gampar hat mit seinen Teutschen das gantz Asiam bekriegt, und das mit seinen ernstlichen namen erfüllet. Daher der nam des kampff oder kempffer als ainer ernstliche hanndlung seinnen ursprung haben soll. Wer aber sich des kampfs zu dem ersten gebraucht, sagt der vorgemelter Aventinus, das ja Hercules der sun Osirs des kunigs der Egiptiern, aus der Isidis die genant wirt Ceres seinen gemahl erboren, den kampff in Teutschlannden, erstlich gebracht habe. Es seind auch ettlich die sagenn, das lang vor dem Troianischen krieg In Arcadia von einem Landfürsten Licaon genant, der kampff gehalten worden sey. Damit aber der guthertzig Leser inn diser rechnung nit irr, oder zweiffelhafftig gemacht werde, soll er wissen, das diser Licaon lang nach dem künig kampffer und dem Herculis gelebt hatt. |

|||||

|

In the year of the world 1484 before the birth of Christ our saviour, Hercules did hold his duel with Antheus, he did lift him up from the ground by his strength and by embracing his abdomen did strongly crush him and asphyxiate him, as he might not otherwise have won. |

Anno Mundi · 1484 · Vor der gepurt Christi vnnsers Hailannds · hat Hercules · mit dem Antheo · seinen kampff gehallten · In auß stercke von der erden aufgehaben · vnd In mit vmbgreiffung der waich in · krefftigelich ertruckt · vnnd also ersteckt · dann er In sunst mit nichten gewinnen mocht · |

Anno mundi 1484 vor der gepurt Christi unnseres Hailannds hat Hercules mit dem Antheo seinen kampff gehalten, in aus stercke von der Erden aufgehoben, und in mit umbgreiffung der waichen, krefftiglich ertruckt, unnd also ersteckt, dann er in sonst mit nichten gewinnen mocht ·/· |

|||||

|

Eusebius[16] writes that Athletes, the first king of the Corinthians, as is also confirmed by the Urspergian abbot,[3] in the year 1088 before the birth of Christ our saviour by his strength and agility did conquer the kingdom of the Cointhians with fencing and duelling, and did reign with good fortune for 35 years. |

Eusebius · schreibet das Athletes · der erst Kunig der Corinthier · Alsdann Abbas Vrspergensis · auch bezeuget · von der geburt Christi vnnsers Hailands · 1088 · Jar · durch sein stercke vnd geschicklichkait · das Kunigreich der Corinthier mit Fechten vnd kempffen · vberkomen · das Funffunddreÿssig Jar glucklich geregiert habe · |

Eusebius schreibt das Athletes der erst künig der Corinther als dann Abbas Urspergensis auch bezeuget, von der gepurt Christi unnsers hailands 1088 jar, durch sein sterck und geschicklichkait, das künigreich der Corinther mit fechten und kempffen überkomen, das 35 jar glücklich geregiert habe. |

|||||

|

Pyrechmen the duellist did defeat Degmemus Etheus in a duel. Likewise did Pitacus Mitilonaus slay Atheus Phrynoneus in a duel. Hector, a son of king Priamus before Troy did hold a duel and earn a knightly vicotry against Ajax. The Great Alexander did hold an armed duel with Porus the king of India, and defeated him by his agility.[17] |

[007r] Virothmen · der Kempffer · hat den Orgmenuen · Etheum In ainnem kampff vberwunden · deßgleichen hat · Pitarus Mitilonaus · den Hauptman von Athen Phrÿnonem · Inn ainnem kampff erlegt · Hector · ein Sun des Kunigs Priami hat vor Troia mit dem Aiacem · ainnen kampff gehallten vnnd dem Ritterlich angesiget Alexander Magnus hat mit Poro · dem Kunig Inn India · ainnen treffenlichen Kampff gehallten vnn den mit seiner geschicklichkait vberwunden / · |

[009*r] Pyrechmen der kempffer, hat den Degmemnum Etheum in ainem kampff überwunden, deszgleichen hat Pitacus Mitilonaus, den haubtman von Athen Phrynonem in ainem kampff erlegt. Hector ain sun des kunigs Priam, hat vor Troia mit Aiacem ainen kampff gehalten, und dem ritterlich angesiget. Alexander Magnus, hat mit Poro dem kunig von India, ainen waffenlich kampff gehalten, unnd den mit seiner geschicklichkait überwunden. |

|||||

|

Likewise did also the royal prophet David honourably defeat the great duellist and giant Goliath. [Lib i. Regnum.] Also Ancheor not without extraordinary agility did lay low Turnus in a duel, and after the Albanians did set their ancestry, glory and reign against the Romans and three strong duellists of Albanian family known as the Cruciati were chosen to duel three Romans with the name of Horace the Horacii on the Roman side with extraordinary agility won the upper hand and slew the Cruciati and thus subjugating all of Italy. Likewise the German who challenged Valerius Corvinus to a duel was slain in a knightly deed. Manlius Torquatus also did kill a German prince in a duel and took off his neck-ring, by this winning great honour for himself and the name of Rome. I will be silent on the duels that were held everywhere in Germany from oldest times. In ancient German writings, kept in Schäbisch Hall, in Kochen[?] and in Würzburg, there are separate duelling rules and many duels were held there. Likewise in Munich on the Iser, Seitz von Althaim and Diepolt Gess in the year 1370 did hold a knightly duel on horseback, in which Seitz von Althaim gained a knightly victory. Likewise in the year 1409 , a knightly duel on foot and in linen shirts behind two shields was held in Augsburg on the Lech on the wine-market between Dieterich Hachsenacker and Wigleo Marschalk, in which duel Marschalk did bravely slay Hachsenacker.[18] The duel did have separate laws and statutes in laws, and their ordering and how they should be held is described and clearly set out in city-books everywhere, treatment of which topic, however, in the interest of brevity I will omit here and will describe and explain it elsewhere. |

Deßgleÿchen hat auch der Kunigelich Prophet Dauid · dem grossen kempffer vnnd Risen · Goliath · eerlich angesiget · Es hat auch Antheor · dem Turno nicht on sonndere geschicklichait Im kampff obgelegen · Vnnd nachdem die Albaneser · all Ir alt herkumen · herrlichait vnnd Regiment an die Römer gesetzet · vnnd dreÿ starck kempffer des Albanesischen geschlechts Cruciaten genannt · an dreÿ der Römer mit Namen Horacÿ zu dem kampff erwöllet wurden · haben die · Horacÿ · auf der Römer seiten mit sonnderer geschicklichait · die obhannd genomen · die Cruciaten erlegt · vnnd also das ganntz Italien dardurch erobert Es ist auch der Teutsch so den Vallerium Eoruinum · zu dem kampff erfordert · Ritterlich erschlagen worden , Manlius Torquatus · hat auch ain Teutschen Fursten Inn dem Kampff erlegt · vnd Im sein · halsband abgezogen · damit Im vnnd dem ganntzen Römischen Namen · groß Eer eingelegt · Ich will geschweigen der Kaempff so Inn Teutschen lannden allenthalben vor allten Zeiten furganngen sein · Man findt Inn alten Teutschen geschrifften · das zu schwaebischen Hall an dem Kochen · vnd zu Wurtzburg · besondere Kampffrecht gehallten · auch vil kämpff alda gehallten worden sein Deßgleichen hat zu Munchen an der Ÿser · Seitz von Althaim vnnd Diepoldt Giß · Anno 1370 · zu Roß ainnen Ritterlichen Kampff gehallten · darInnen der Seÿtz von Althaim Ritterlich obgesiget hat · Deßgeleichen hat Diethrich Hachsenacker · mit dem Wigleus Marschalckh zu Augspurg am Lech · Anno · 1409 · an dem Weinmarckt zu Fuß Inn Hemmeter · Hinder zwaien Schildten · Ritterlich gekempffet · Inn welichem Kampff der Marschalck den Hachsenacker [007v] tapffer erlegt hat · Es haben auch die Kämpff Ire sondere Recht vnnd Statuten Im rechten · vnnd daneben · werden Ire ordnungen · wie die gehallten werden sollen · Inn den Statbuechern allenthalben beschriben · klar befunden · welchs aber vmb kurtz willen alhie zumelden · vnnderlassen · Vnnd an anndern orten beschriben vnnd außgefuert werden soll · |

Deszglaichen hat auch der kuniglich prophet David dem grossen kampffer und risen Goliath eerlich angesiget.Lib i. Regnum. Es hat auch Ancheor dem Turno nicht on sonder geschicklichkait im kamff abgelegen, unnd nachdem die ALbaneser all ir alt herkomen, herrlichkait und regiment an die römer gesetzet, unnd drey starck kempffer des Albanesischen geschlechts Cruciaten genant an drey die römer mit namen Horacii, zu dem kampff erwelet wurden, haben die Horacii auff der römer sitten mit sonderer geschicklichkait, die obhand genomen, die Cruciaten erlegt, und also das gantz Italien dardurch erobert. Es ist auch der Teutsch so den Valerium Corvinum zu dem kampff erfordert, ritterlich erschlagren worden. Manlius Torquatus hat auch ain Teuschen fürsten in dem kampff erlegtt, und im sain halszband abgezogen, damit in und dem gantz römischen namen, grosz eer eingelegt. Ich will geschweigen der kämpff so in Teutschlanden allenthalben vor alten zeitten fürgangen saind. Man findet in alten Teutschen geschrifften, das zu schwäbischn hall an dem Kochen und zu Würtzburg, besondere kampffrecht gehalten, auch vil kämpff alda gehalten worden sind. Deszglaichen hat zu münchen an der Yser, Seitz von Althaim unnd Diepolt Gesz anno .1370. zu rosz ainen ritterlich kampff gehalten, darinnen der Seitz von Althaim ritterlich obgesiget hat. Deszgelaichen hat Dieterich Hachsenacker mit dem Wigluso Marschalck zu Augspurg am Lech anno .1409. an dem Wainmarckt zu fusz in hemmeter hinder zwaien schilten, ritterlich gekempffet, inn welchem kampff der marschalck den hachsenacker tapffer erlegt hat. Es haben auch die kämpff in sondere recht unnd statuta in rechten, und daneben werden ire ordnung, wie die gehalten werden söllen, inn den statbüechern allenthalben beschriben, clar befunden, welches aber umb kürtz willen alhie zumelden, underlassen, und an anderen orten beschriben und auszgefüert werden soll. |

|||||

|