|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Nicoletto Giganti"

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | class="noline" | <p>'''By Nicoletto Giganti, Venetian, To The Most Serene Don Cosmo | + | | class="noline" | <p>'''By Nicoletto Giganti, Venetian, To The Most Serene Don Cosmo De’ Medici Great Prince Of Tuscany'''</p> |

| class="noline" | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/5|2|lbl=-}} | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/5|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| class="noline" | | | class="noline" | | ||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

|- | |- | ||

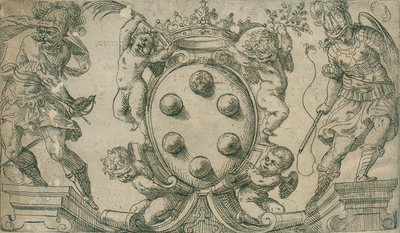

| [[File:Giganti Medici Heraldry.png|400x400px|center|Arms of the Medici Family]] | | [[File:Giganti Medici Heraldry.png|400x400px|center|Arms of the Medici Family]] | ||

| − | | <p>''' | + | | <p>'''To the Most Serene Don Cosmo de Medici Great Prince of Tuscany''' my only Lord</p> |

<p>Just as iron extracted from the rough mines would be useless if it had not received shape suited to human armies from industrious art, thus the same in the hands of the strong soldier can be of little profit if, accompanied by studious and wise valour, the way is not made clear for every difficult and triumphant success. In this way to a point since the Good Shepherd welcomes the operation, because almost all the noblest things proceeding from our actions receive appropriate material from His hands, which, refined and dignified by the industry of the spirit, achieve miraculous and powerful effects. Now I say that this temperament is wonderfully demonstrated in the excellent and illustrious greatness of Your Most Serene Highness, who holds the natural greatnesses brought back to their peak from the invincible glorious works of your Ancestors, not only in the ancient and royal histories, but reflecting in yourself all the light of the present and past splendour, adorning them with your own virtues so that everyone admires the most divine tempers, and with wonderment says such a Most Serene Lord is no less fitting to that Most Serene State, than such a Most Serene State to that Most Serene Lord. But I will only say that this proposition, just as is demonstrated clearly in all the arts; so it is evidently perceived in exercising arms. Discussing the strength of iron, although it is exercised by a strong arm and agile body, if it is not tuned with observed rules and exercised study it is shown to be perilous and of little valour: Whereas if the art can be known by a wise captain, and he obeys it as a bold minister, they make marvelous prowess of it. You serve us as a clear example, who Heaven had to grant all height of perfect quality as in the most complete illumination of the present age. You who have in the noblest proportion stature, puissance, vigour joined to agility, promptness, and strength, in order to draw with your highest ingenuity the finesse of industry, advice, time, and art that can make you most a complete and Most Illustrious Captain, a Most Serene and most singular Prince.</p> | <p>Just as iron extracted from the rough mines would be useless if it had not received shape suited to human armies from industrious art, thus the same in the hands of the strong soldier can be of little profit if, accompanied by studious and wise valour, the way is not made clear for every difficult and triumphant success. In this way to a point since the Good Shepherd welcomes the operation, because almost all the noblest things proceeding from our actions receive appropriate material from His hands, which, refined and dignified by the industry of the spirit, achieve miraculous and powerful effects. Now I say that this temperament is wonderfully demonstrated in the excellent and illustrious greatness of Your Most Serene Highness, who holds the natural greatnesses brought back to their peak from the invincible glorious works of your Ancestors, not only in the ancient and royal histories, but reflecting in yourself all the light of the present and past splendour, adorning them with your own virtues so that everyone admires the most divine tempers, and with wonderment says such a Most Serene Lord is no less fitting to that Most Serene State, than such a Most Serene State to that Most Serene Lord. But I will only say that this proposition, just as is demonstrated clearly in all the arts; so it is evidently perceived in exercising arms. Discussing the strength of iron, although it is exercised by a strong arm and agile body, if it is not tuned with observed rules and exercised study it is shown to be perilous and of little valour: Whereas if the art can be known by a wise captain, and he obeys it as a bold minister, they make marvelous prowess of it. You serve us as a clear example, who Heaven had to grant all height of perfect quality as in the most complete illumination of the present age. You who have in the noblest proportion stature, puissance, vigour joined to agility, promptness, and strength, in order to draw with your highest ingenuity the finesse of industry, advice, time, and art that can make you most a complete and Most Illustrious Captain, a Most Serene and most singular Prince.</p> | ||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>Wherefore I, recognizing and admiring with humblest affection the mature splendour of your newly made and happy years, and reading in the face of the world the secure hopes and fruits of the future age, adoring that hand from which Italy and the entire world is taking safe rest and glorious protection, to that I offer and consecrate with humble dedication this small, I will certainly not say fruit, but work of my labours. Therefore, it only must please you, being of material welcomed by you which deigns to bend your Most Serene eye. To that end, let many of your highest rays pass over where the baseness of my ingenuity with the exercise of this art that I have dealt with for 27 years does not arrive. Let this work, in itself humble, present itself happily to the view of the World. It will be effected with the action of my devotion, together with the fruit of your Most Serene mercy, who serving being the full glory, I pray that Heaven makes me a worthy, even lowest servant. In Venice February 10, 1606</p> | + | | <p>Wherefore I, recognizing and admiring with humblest affection the mature splendour of your newly made and happy years, and reading in the face of the world the secure hopes and fruits of the future age, adoring that hand from which Italy and the entire world is taking safe rest and glorious protection, to that I offer and consecrate with humble dedication this small, I will certainly not say fruit, but work of my labours. Therefore, it only must please you, being of material welcomed by you which deigns to bend your Most Serene eye. To that end, let many of your highest rays pass over where the baseness of my ingenuity with the exercise of this art that I have dealt with for 27 years does not arrive. Let this work, in itself humble, present itself happily to the view of the World. It will be effected with the action of my devotion, together with the fruit of your Most Serene mercy, who serving being the full glory, I pray that Heaven makes me a worthy, even lowest servant. In Venice February 10, 1606.</p> |

:Of Your Most Serene Highness, | :Of Your Most Serene Highness, | ||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Nicoletto Giganti portrait.png|400x400px|center|Nicoletto Giganti]] | | [[File:Nicoletto Giganti portrait.png|400x400px|center|Nicoletto Giganti]] | ||

| − | | <p>''' | + | | <p>'''To the Lord Readers, Almoro Lombardo,''' Son of the Most Renowned Lord Marco.</p> |

<p>''Wanting to write on the matter of arms, although the author does not mention that it is a science, to me it appears a necessary thing, Lord Readers, to treat with what share it has, and of which name it would adorn itself so that everyone knows its greatness, dignity, and privilege.''</p> | <p>''Wanting to write on the matter of arms, although the author does not mention that it is a science, to me it appears a necessary thing, Lord Readers, to treat with what share it has, and of which name it would adorn itself so that everyone knows its greatness, dignity, and privilege.''</p> | ||

| Line 141: | Line 141: | ||

<p>''The object of this science is nothing more than parrying and wounding. The knowledge of those two things is a work of the intellect, and moreover with intelligence professors of this science do not extend it further than the knowledge of them, which cannot be understood at all unless one first has knowledge of tempi and measures, or rather, knowledge of Feint, Disengage, or resolution without knowledge of tempi and measures. These are all operations of the intellect, and moreover outside of this knowledge the intellect does not extend, because as I have said the aim of these professions is understanding parrying. We will see if it is Real Speculative or Rational Speculative.''</p> | <p>''The object of this science is nothing more than parrying and wounding. The knowledge of those two things is a work of the intellect, and moreover with intelligence professors of this science do not extend it further than the knowledge of them, which cannot be understood at all unless one first has knowledge of tempi and measures, or rather, knowledge of Feint, Disengage, or resolution without knowledge of tempi and measures. These are all operations of the intellect, and moreover outside of this knowledge the intellect does not extend, because as I have said the aim of these professions is understanding parrying. We will see if it is Real Speculative or Rational Speculative.''</p> | ||

| − | <p>''Considering this, it cannot be Rational, and the reason is this: because if it is indeed an operation of the intellect, nevertheless it spreads further, wherefore I find it to be Real Speculative. Real, because the knowledge of its aim is shown to us outwardly by the intellect. As the understanding of wounding and parrying, with tempi, measures, feints, disengages, and resolutions, even though they are operations of the intellect, they cannot be understood if not outwardly, and this exterior consists in the bearing of the body and of the Sword in the guards and counterguards, which all consist of circles, angles, lines, surfaces, measures, and of numbers. These things, which must be observed, can be read about in Camillo Agrippa and in many other professors of this science. Note that just as those operations of the intellect without an exterior operation cannot be shown, so these exterior operations cannot be understood without the operations of the intellect first, in a manner that this science, which derives from the intellect, cannot be understood if not outwardly. Neither can one understand outwardly without operations of the intellect. These operations seek to understand the greatness, excellence, and perfection of this profession, and always come united. As there can never be Sun without day, nor day without Sun, never will there be those without these, nor these without those. In the end we see that it is Real Speculative Science.''</p> | + | <p>''Considering this, it cannot be Rational, and the reason is this: because if it is indeed an operation of the intellect, nevertheless it spreads further, wherefore I find it to be Real Speculative. Real, because the knowledge of its aim is shown to us outwardly by the intellect. As the understanding of wounding and parrying, with tempi, measures, feints, disengages, and resolutions, even though they are operations of the intellect, they cannot be understood if not outwardly, and this exterior consists in the bearing of the body and of the Sword in the guards and counterguards, which all consist of circles, angles, lines, surfaces, measures, and of numbers.'''</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>''These things, which must be observed, can be read about in Camillo Agrippa and in many other professors of this science. Note that just as those operations of the intellect without an exterior operation cannot be shown, so these exterior operations cannot be understood without the operations of the intellect first, in a manner that this science, which derives from the intellect, cannot be understood if not outwardly. Neither can one understand outwardly without operations of the intellect. These operations seek to understand the greatness, excellence, and perfection of this profession, and always come united. As there can never be Sun without day, nor day without Sun, never will there be those without these, nor these without those. In the end we see that it is Real Speculative Science.''</p> | ||

<p>''This science of the Sword, or of arms, is a Real Speculative Mathematic Science, and Geometric, and Arithmetic. Geometric because it consists in lines, circles, angles, surfaces, and measures. Arithmetic because it consists of numbers. There is no motion of the body that does not make an angle or constraint. There is no motion of the Sword that does not travel in a line. There is neither guard nor counterguard that does not go by the number. The observations of these things all depend on knowledge of tempi and measures, whence I conclude that this most noble science is Real, Mathematic, Geometric, and Arithmetic, as I said a little above.''</p> | <p>''This science of the Sword, or of arms, is a Real Speculative Mathematic Science, and Geometric, and Arithmetic. Geometric because it consists in lines, circles, angles, surfaces, and measures. Arithmetic because it consists of numbers. There is no motion of the body that does not make an angle or constraint. There is no motion of the Sword that does not travel in a line. There is neither guard nor counterguard that does not go by the number. The observations of these things all depend on knowledge of tempi and measures, whence I conclude that this most noble science is Real, Mathematic, Geometric, and Arithmetic, as I said a little above.''</p> | ||

| Line 171: | Line 173: | ||

<p>''Therefore, just as it is of great dignity, because it is real Speculative Mathematics of Geometry and Arithmetic, and for many parts found under itself, such decorum and reputation I say it requires. No other will be the decorum and reputation if not this. And also considering, o Readers, that this science for the most part is found in royal courts, and of every Prince, in the most famous Cities, studied by Barons, Counts, Knights, and persons of great quality, and for no other reason if not because just as it is noble, it excites and inflames our spirits to great things, to learn, and to heroic actions, to match of the virtue of the spirit, the valour of the body, the vigour of the strength, and the skill of the person. This always seeks parity, and does not allow any blemish to it. It wants to be understood and learned, but not to be professed for every folly one takes up. It flees the disputes of villainous persons. It does not do all that it can. It shows itself at the time and place. It avoids the practices of excess. It is of few words. It desires a serious comportment, a lively eye, an honoured dress, and a noble practice. This is enough about its decorum and reputation. In regard to the honour that it requires, advising that the observance of all the said things is honour to this profession, it remains only to be said what obligation one who carries the sword is under.''</p> | <p>''Therefore, just as it is of great dignity, because it is real Speculative Mathematics of Geometry and Arithmetic, and for many parts found under itself, such decorum and reputation I say it requires. No other will be the decorum and reputation if not this. And also considering, o Readers, that this science for the most part is found in royal courts, and of every Prince, in the most famous Cities, studied by Barons, Counts, Knights, and persons of great quality, and for no other reason if not because just as it is noble, it excites and inflames our spirits to great things, to learn, and to heroic actions, to match of the virtue of the spirit, the valour of the body, the vigour of the strength, and the skill of the person. This always seeks parity, and does not allow any blemish to it. It wants to be understood and learned, but not to be professed for every folly one takes up. It flees the disputes of villainous persons. It does not do all that it can. It shows itself at the time and place. It avoids the practices of excess. It is of few words. It desires a serious comportment, a lively eye, an honoured dress, and a noble practice. This is enough about its decorum and reputation. In regard to the honour that it requires, advising that the observance of all the said things is honour to this profession, it remains only to be said what obligation one who carries the sword is under.''</p> | ||

| − | <p>''We will pass by the aims of these | + | <p>''We will pass by the aims of these Duelists who, just as they have badly learned the said profession, so I say with many of their propositions they degrade it and have reduced it to such an unhappy state that it not only casts aside the virtuous life which demands such a science, and human discourse, and every reason, but forgetting the great God, and themselves as a consequence, their unjust aims can only possess it for the damnation of their spirits, postponing the divine church for their diabolical thoughts.''</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/13|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|14|lbl=x|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|15|lbl=xi|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|16|lbl=xii|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|17|lbl=xiii|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/13|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|14|lbl=x|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|15|lbl=xi|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|16|lbl=xii|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|17|lbl=xiii|p=1}} | ||

| Line 194: | Line 196: | ||

:Dated the 31st of October, 1605. | :Dated the 31st of October, 1605. | ||

| − | ::Captains of the Most Illustrious Council of X | + | ::Captains of the Most Illustrious Council of X. |

::D. Santo Balbi<br/>D. Gio. Giacomo Zane<br/>D. Piero Barbarigo | ::D. Santo Balbi<br/>D. Gio. Giacomo Zane<br/>D. Piero Barbarigo | ||

| Line 254: | Line 256: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[3] As for the counterguards, be advised that one who has knowledge of this profession will never place themselves in guard, but will seek to place themselves against the guards.<ref name="counterguard">In a counterguard.</ref> Wanting to do so, be warned of this: one must place oneself outside of measure, that is, at a distance, with the sword and dagger high, strong with the vita, and with a firm and balanced pace, then consider the guard of the enemy. Afterwards approach him little by little with your sword binding his for safety, that is, almost resting your sword on his so that it covers it because he will not be able to wound if he does not disengage the sword. The reason for this is that in disengaging he performs two actions. First he disengages, which is the first tempo, then wounding, which is the second. While he disengages, in that same tempo he can come to be wounded in many ways before he has time to wound, as one will see in the figures of my book. If he changes guard for the counterguard it is necessary to follow him along with the sword forward and the dagger, always securing his sword, because in the first tempo he will always have to disengage the sword and end up wounded. It will never be possible for him to wound if not with two tempi, and from those parrying will always be a very easy thing. This is enough about guards and counterguards.</p> | + | | <p>[3] As for the counterguards, be advised that one who has knowledge of this profession will never place themselves in guard, but will seek to place themselves against the guards. <ref name="counterguard">In a counterguard.</ref> Wanting to do so, be warned of this: one must place oneself outside of measure, that is, at a distance, with the sword and dagger high, strong with the vita, and with a firm and balanced pace, then consider the guard of the enemy. Afterwards approach him little by little with your sword binding his for safety, that is, almost resting your sword on his so that it covers it because he will not be able to wound if he does not disengage the sword. The reason for this is that in disengaging he performs two actions. First he disengages, which is the first tempo, then wounding, which is the second. While he disengages, in that same tempo he can come to be wounded in many ways before he has time to wound, as one will see in the figures of my book. If he changes guard for the counterguard it is necessary to follow him along with the sword forward and the dagger, always securing his sword, because in the first tempo he will always have to disengage the sword and end up wounded. It will never be possible for him to wound if not with two tempi, and from those parrying will always be a very easy thing. This is enough about guards and counterguards.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 265: | Line 267: | ||

| <p>[4] '''Tempo and Measure'''</p> | | <p>[4] '''Tempo and Measure'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>One cannot know how to place oneself in guard, or against the guard,<ref name="counterguard"/> nor how to throw a thrust, an imbroccata, a mandritto, or a riverso, nor how to turn the wrist, nor how to carry the body well, or to best control the sword, or say one understands parrying and wounding, but by understanding tempo and measure which, of one who does not understand, even though they parry and wound, it could not be said that they understand parrying and wounding, because such a person in parrying as in wounding can err and incur a thousand dangers.</p> | + | <p>One cannot know how to place oneself in guard, or against the guard, <ref name="counterguard"/> nor how to throw a thrust, an imbroccata, a mandritto, or a riverso, nor how to turn the wrist, nor how to carry the body well, or to best control the sword, or say one understands parrying and wounding, but by understanding tempo and measure which, of one who does not understand, even though they parry and wound, it could not be said that they understand parrying and wounding, because such a person in parrying as in wounding can err and incur a thousand dangers.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/24|1|lbl=04}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/24|1|lbl=04}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/12|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/12|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 296: | Line 298: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[8] If he disengages, in the disengagement one can wound him, and this is a tempo. If he changes guard, while he changes is a tempo. If he turns, it is a tempo. If he binds to come to measure, while he walks before arriving in measure is a tempo to wound him. If he throws, parrying and wounding in a tempo also is a tempo. If the enemy stays still in guard and waits and you advance to bind him and throw where he is uncovered when you are in measure, it is a tempo, because in every motion of the dagger, sword, foot, and vita such as changing guard, is a tempo in such a way that all these things are tempi: because they contain different intervals, and while the enemy makes one of these motions, he will certainly be wounded because while a person moves they cannot wound. It is necessary to understand this in order to be able to wound and parry. I will be demonstrating more clearly how one must do so in my figures.</p> | + | | <p>[8] If he disengages, in the disengagement one can wound him, and this is a tempo. If he changes guard, while he changes is a tempo. If he turns, it is a tempo. If he binds to come to measure, while he walks before arriving in measure is a tempo to wound him. If he throws, parrying and wounding in a tempo also is a tempo. If the enemy stays still in guard and waits and you advance to bind him and throw where he is uncovered when you are in measure, it is a tempo, because in every motion of the dagger, sword, foot, and vita such as changing guard, is a tempo in such a way that all these things are tempi: because they contain different intervals, and while the enemy makes one of these motions, he will certainly be wounded 10 because while a person moves they cannot wound. It is necessary to understand this in order to be able to wound and parry. I will be demonstrating more clearly how one must do so in my figures.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/25|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/25|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/13|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/13|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 360: | Line 362: | ||

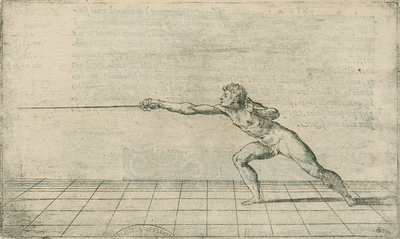

| <p>[15] '''Explanation of Wounding in Tempo'''</p> | | <p>[15] '''Explanation of Wounding in Tempo'''</p> | ||

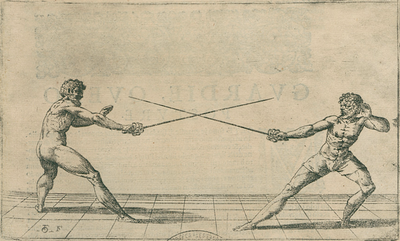

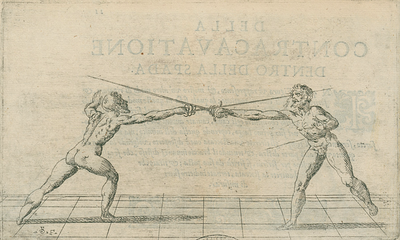

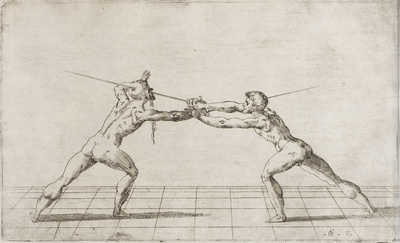

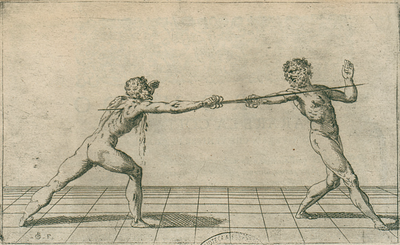

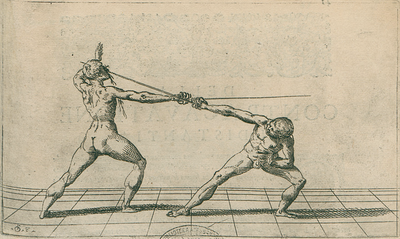

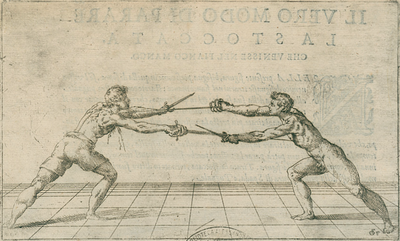

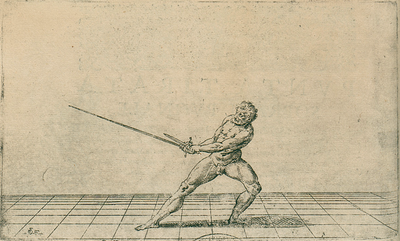

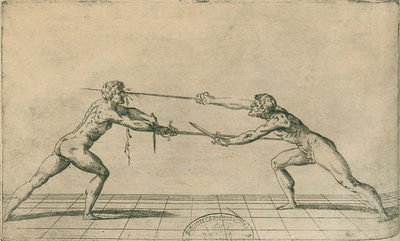

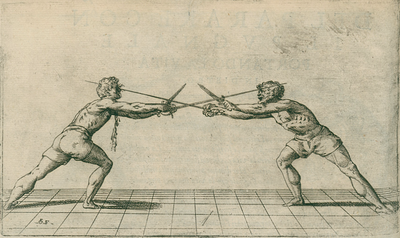

| − | <p>This figure teaches you to wound your enemy in the tempo he disengages his sword. You do this by approaching to bind the enemy outside of measure, placing your sword over his to the inside as the figure of the first guard | + | <p>This figure teaches you to wound your enemy in the tempo he disengages his sword. You do this by approaching to bind the enemy outside of measure, placing your sword over his to the inside as the figure of the first guard<ref>Although the plates depicting the guards and counterguards are somewhat less than clear, we know from this chapter that Figure 2 depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the inside.</ref> shows you so that he will not be able to wound you if he does not disengage the sword. Then, in the same tempo that he disengages to wound you, push forward your sword, turning your wrist in the same tempo so that you wound him in the face as is seen in the figure. In the case that you were to parry and then wound it would not be successful, since the enemy would have tempo to parry and you would be in danger, but if you enter immediately forward with your sword in the tempo he disengages his, turning your wrist and parrying, the enemy will have difficulty parrying.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/33|1|lbl=13}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/33|1|lbl=13}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/21|1|lbl=09}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/21|1|lbl=09}} | ||

| Line 380: | Line 382: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 05.png|400x400px|center|Figure 5]] | | [[File:Giganti 05.png|400x400px|center|Figure 5]] | ||

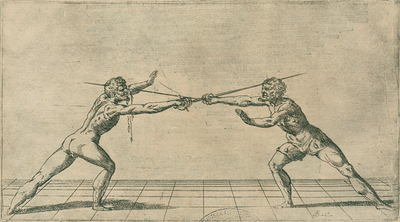

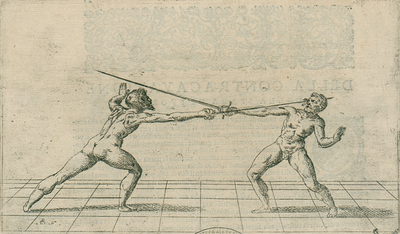

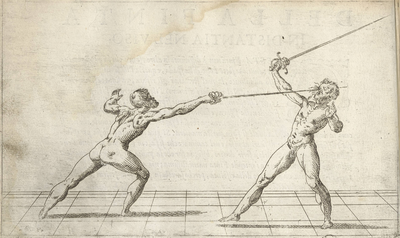

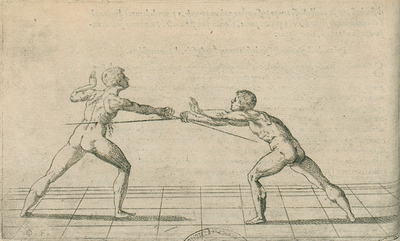

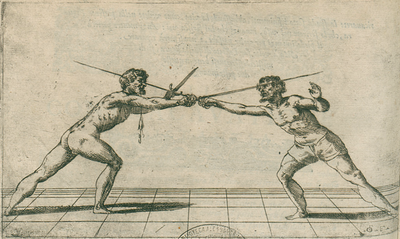

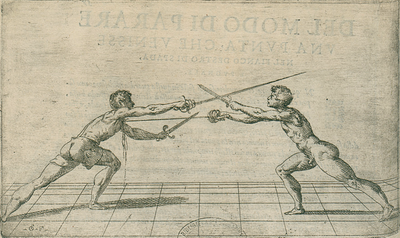

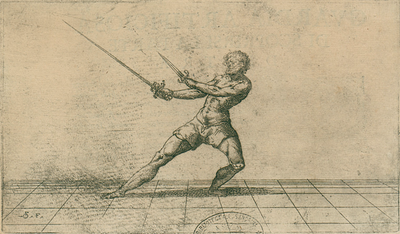

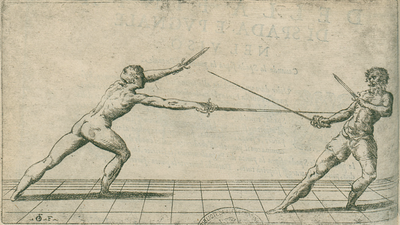

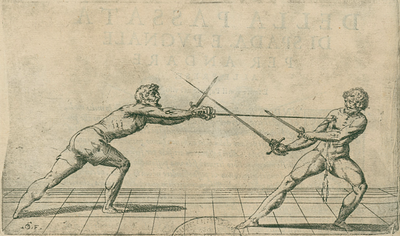

| − | | <p>[18] '''The Proper Method of Going to Bind the Enemy and Strike Him | + | | <p>[18] '''The Proper Method of Going to Bind''' the Enemy and Strike Him while he disengages the sword</p> |

| − | <p>From this figure you learn that if your enemy is in a guard with the sword on the left side, high or low, you approach him to bind him outside of his sword outside of measure, with your sword over his so that it barely touches it, with a just and strong pace, with your sword ready to parry and wound, with lively eyes, as you see in the second figure of the guards and counterguards.<ref>Figure 3, which we know from the description of this chapter’s action depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the outside.</ref> You being accommodated in this way, your enemy will not be able to wound you with a thrust if he does not disengage the sword. While he disengages, turn your wrist and in the same tempo throw a stoccata at him as the fourth figure teaches you. Having thrown this stoccata, immediately in the same tempo return backward outside of measure, resting your sword over his so that if he wants to disengage anew, you will return to throw to him the same stoccata, turning your wrist as above, returning outside of measure. As many times as he disengages, that many times you will use the same method of turning your wrist and throwing the stoccata at him.</p> | + | <p>From this figure you learn that if your enemy is in a guard with the sword on the left side, high or low, you approach him to bind him outside of his sword outside of measure, with your sword over his so that it barely touches it, with a just and strong pace, with your sword ready to parry and wound, with lively eyes, as you see in the second figure of the guards and counterguards. <ref>Figure 3, which we know from the description of this chapter’s action depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the outside.</ref> You being accommodated in this way, your enemy will not be able to wound you with a thrust if he does not disengage the sword. While he disengages, turn your wrist and in the same tempo throw a stoccata at him as the fourth figure teaches you. Having thrown this stoccata, immediately in the same tempo return backward outside of measure, resting your sword over his so that if he wants to disengage anew, you will return to throw to him the same stoccata, turning your wrist as above, returning outside of measure. As many times as he disengages, that many times you will use the same method of turning your wrist and throwing the stoccata at him.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/35|1|lbl=15}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/35|1|lbl=15}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/23|1|lbl=10}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/23|1|lbl=10}} | ||

| Line 436: | Line 438: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 08.png|400x400px|center|Figure 8]] | | [[File:Giganti 08.png|400x400px|center|Figure 8]] | ||

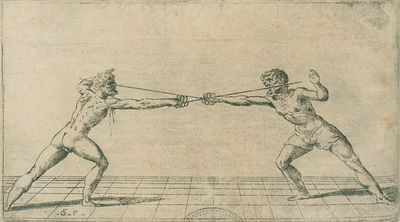

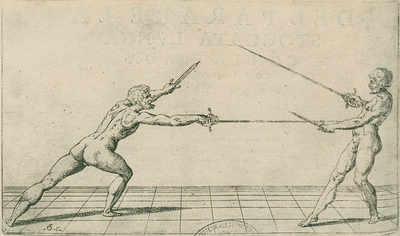

| − | | <p>[24] '''Explanation of the Feint,''' ''Making a show of disengaging the sword with your wrist'' | + | | <p>[24] '''Explanation of the Feint,''' ''Making a show of disengaging the sword with your wrist''</p> |

| − | <p>The ways of wounding are various and as a consequence my lessons are also various. But don’t expect at all that I will tell all the things that are possible to do in this profession because, those being infinite, my work would be too long and would bring tedium to the Readers. However, I will untangle those things that to me appear most beautiful, most artificial, and most useful, from which arise many others easier and less artificial.</p> | + | <p>The ways of wounding are various and as a consequence my lessons are also various. But don’t expect at all that I will tell all the things that are possible to do in this profession because, those being infinite, my work would be too long and would bring tedium to the Readers. However, I will untangle those things that to me appear most beautiful, most artificial, and most useful, from which arise many others easier and less artificial. </p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/43|1|lbl=23}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/43|1|lbl=23}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/30|1|lbl=14}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/30|1|lbl=14}} | ||

| Line 455: | Line 457: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[26] The feint is therefore performed in this way: first one displays the sword to either the face or chest of the enemy, and then one lengthens the arm without stepping. If the enemy parries, disengage the sword in the same tempo, accompanying it forward with the step so that you wound him unawares. </p> | + | | <p>[26] The feint is therefore performed in this way: first one displays the sword to either the face or chest of the enemy, and then one lengthens the arm without stepping. If the enemy parries, disengage the sword in the same tempo, accompanying it forward with the step so that you wound him unawares.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 478: | Line 480: | ||

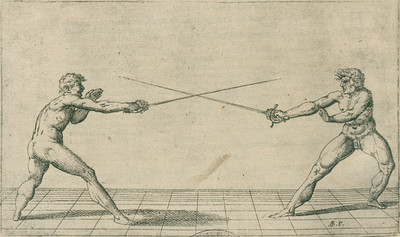

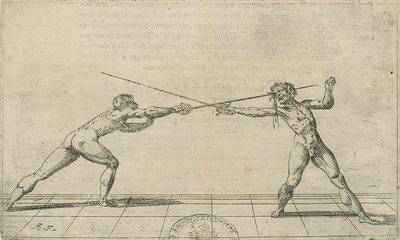

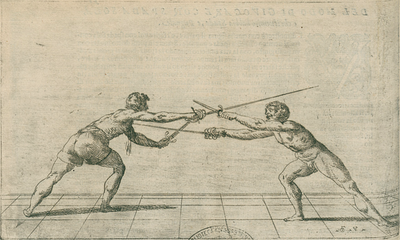

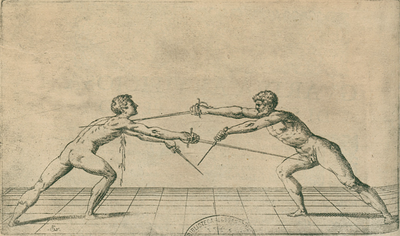

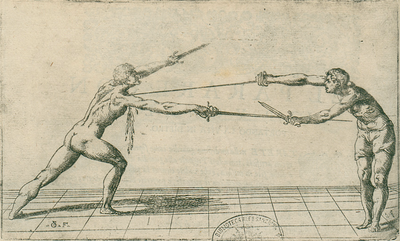

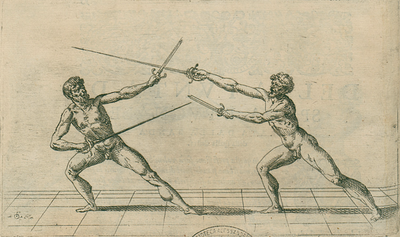

| <p>[29] '''Method of Wounding in the Chest with the Single Sword When They<ref>The two fencers.</ref> Are In''' measure with the swords equal</p> | | <p>[29] '''Method of Wounding in the Chest with the Single Sword When They<ref>The two fencers.</ref> Are In''' measure with the swords equal</p> | ||

| − | <p>The present figure is an artificial way of wounding the enemy in the chest and securing oneself from his sword so that he cannot offend while you pass to wound him. It is done in this way: one needs to place themselves in guard with the sword forward on the left side and if the enemy comes to bind you and cover your sword with his let him come until he finds himself in measure with you. When he is in measure with you disengage, putting your sword inside of his, straightening the point against the enemy’s face. If he does not go to parry, wound him resolutely, going as I have said above with the right edge of yours on the edge of his, turning your wrist and carrying the body across a bit. But if the enemy comes to parry and wound you while you disengage do not throw the thrust but hold it a little outside, and in the same tempo that he wants to parry and wound, redisengage your sword under the hilt of his, done aiming at the chest of the enemy so that you strike him in the chest safely, increasing a little with the sword, as you see in the present figure. | + | <p>The present figure is an artificial way of wounding the enemy in the chest and securing oneself from his sword so that he cannot offend while you pass to wound him. It is done in this way: one needs to place themselves in guard with the sword forward on the left side and if the enemy comes to bind you and cover your sword with his let him come until he finds himself in measure with you. When he is in measure with you disengage, putting your sword inside of his, straightening the point against the enemy’s face. If he does not go to parry, wound him resolutely, going as I have said above with the right edge of yours on the edge of his, turning your wrist and carrying the body across a bit. But if the enemy comes to parry and wound you while you disengage do not throw the thrust but hold it a little outside, and in the same tempo that he wants to parry and wound, redisengage your sword under the hilt of his, done aiming at the chest of the enemy so that you strike him in the chest safely, increasing a little with the sword, as you see in the present figure.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/47|1|lbl=27}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/47|1|lbl=27}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/33|1|lbl=16}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/33|1|lbl=16}} | ||

| Line 485: | Line 487: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[30] Take care to disengage and redisengage it in the same tempo, never holding it still so that the enemy does not find it. In the movement he makes to parry, pass to him with your vita on the outside, taking care to place your hand on the hilt of the sword. This pass makes this effect: he takes the chance to wound you and you can wound him how and where you like and please. | + | | <p>[30] Take care to disengage and redisengage it in the same tempo, never holding it still so that the enemy does not find it. In the movement he makes to parry, pass to him with your vita on the outside, taking care to place your hand on the hilt of the sword. This pass makes this effect: he takes the chance to wound you and you can wound him how and where you like and please.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/47|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/47|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/33|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/33|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 519: | Line 521: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 12.png|400x400px|center|Figure 12]] | | [[File:Giganti 12.png|400x400px|center|Figure 12]] | ||

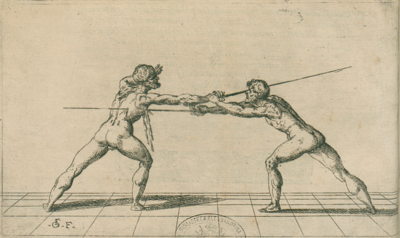

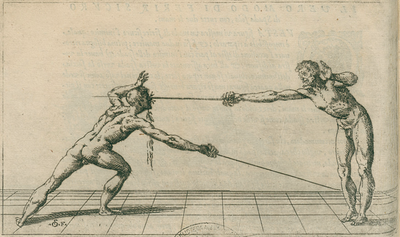

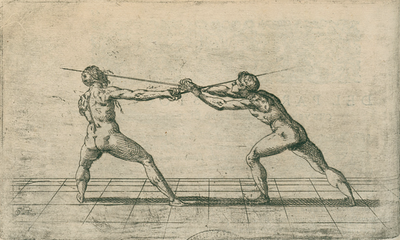

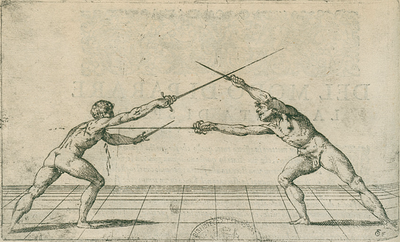

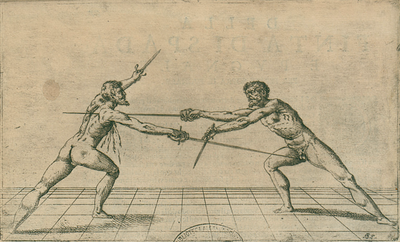

| − | | <p>[34] '''The Proper Method to Give a Thrust with the Single Sword while the Enemy Throws''' a | + | | <p>[34] '''The Proper Method to Give a Thrust with the Single Sword while the Enemy Throws''' a cut</p> |

<p>This figure teaches you to avail yourself of the tempo in order to give your enemy a stoccata to the face while he raises the sword, if he can be given a stoccata while his sword is in the air, and before he reaches you. Note how this is done. After having placed yourself in whichever guard you like, go to bind your enemy and when you are in measure if the enemy throws a cut toward your head, in the raising of the sword you make use of the tempo, enter forward, and throw the sword at his face so that without doubt you wound him while the enemy sword is in the air, as you see in the figure. But, in throwing turn the inside of your wrist and the right edge of the sword upwards, holding your arm long and high, and make the guard of your sword cover your head so that if the enemy disengages his sword he would find you covered and it will not be possible to offend you.</p> | <p>This figure teaches you to avail yourself of the tempo in order to give your enemy a stoccata to the face while he raises the sword, if he can be given a stoccata while his sword is in the air, and before he reaches you. Note how this is done. After having placed yourself in whichever guard you like, go to bind your enemy and when you are in measure if the enemy throws a cut toward your head, in the raising of the sword you make use of the tempo, enter forward, and throw the sword at his face so that without doubt you wound him while the enemy sword is in the air, as you see in the figure. But, in throwing turn the inside of your wrist and the right edge of the sword upwards, holding your arm long and high, and make the guard of your sword cover your head so that if the enemy disengages his sword he would find you covered and it will not be possible to offend you.</p> | ||

| Line 542: | Line 544: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 13.png|400x400px|center|Figure 13]] | | [[File:Giganti 13.png|400x400px|center|Figure 13]] | ||

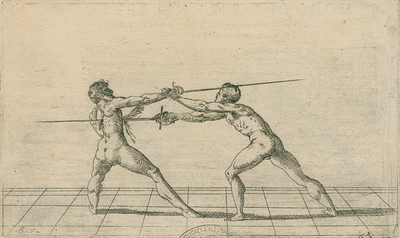

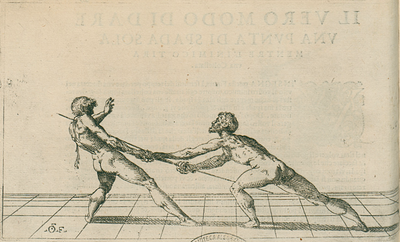

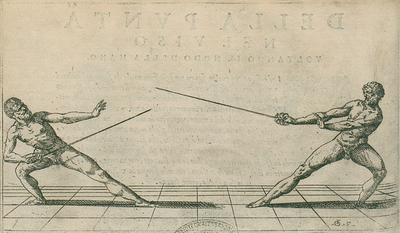

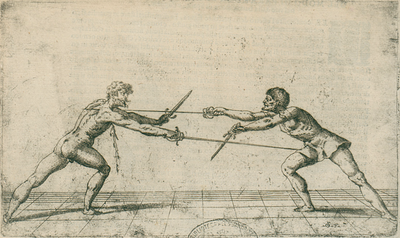

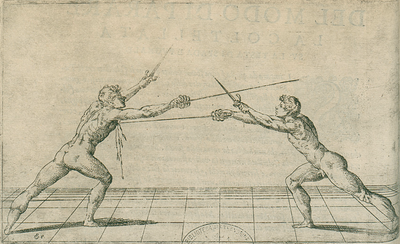

| − | | <p>[37] '''The Proper Way to Safely Wound''' with | + | | <p>[37] '''The Proper Way to Safely Wound''' with the single sword using both hands</p> |

<p>This figure shows you a method of safely wounding the enemy which is impossible to parry. It is done in two manners. First one needs to find the occasion to have your sword equal with the enemy’s, having yours outside, then affront your sword toward the enemy’s face which, if not parried strongly, strikes him in the face as is seen in the fourth figure. If he parries well and strongly, increase with your left foot, putting your left hand over your sword, driving strongly with both hands, straightening the point against the enemy’s chest and lowering the hilt of your sword as is seen in the present figure, taking care to do all these things in one tempo.</p> | <p>This figure shows you a method of safely wounding the enemy which is impossible to parry. It is done in two manners. First one needs to find the occasion to have your sword equal with the enemy’s, having yours outside, then affront your sword toward the enemy’s face which, if not parried strongly, strikes him in the face as is seen in the fourth figure. If he parries well and strongly, increase with your left foot, putting your left hand over your sword, driving strongly with both hands, straightening the point against the enemy’s chest and lowering the hilt of your sword as is seen in the present figure, taking care to do all these things in one tempo.</p> | ||

| Line 576: | Line 578: | ||

| <p>[41] '''The Inquartata''' or Slip of the Vita</p> | | <p>[41] '''The Inquartata''' or Slip of the Vita</p> | ||

| − | <p>Knowing the inquartata, or slip, is necessary in order to master the body. But this not ordinarily used in the schools, except by the French in order to exercise the body. In truth many are these slips, or inquartate, but I judged in my first book to show only three of them, in my judgement the safest and most beautiful, as appears in the present figure.</p> | + | <p>Knowing the inquartata, or slip, is necessary in order to master the body. But this not ordinarily used in the schools, except by the French in order to exercise the body. In truth many are these slips, or inquartate, but I judged in my first book to show only three of them, in my judgement the safest and most beautiful, as appears in the present figure. </p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/59|1|lbl=39}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/59|1|lbl=39}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/46|1|lbl=23}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/46|1|lbl=23}} | ||

| Line 662: | Line 664: | ||

| rowspan="2" | <p>[51] '''The Counterdisengage at a Distance'''</p> | | rowspan="2" | <p>[51] '''The Counterdisengage at a Distance'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>This<ref>The two preceding figures.</ref> is one and the same counterdisengage at a distance against one who has their left foot forward and wants to pass by inquartata. I wanted to demonstrate to you with this figure the postures and wound so that it is possible to comprehend it well for the sake of necessity (when one is coming to bind you with their left foot forward). Stand in guard as you see in this figure, giving occasion to your enemy to throw at your chest. If he is a valiant man he will pass with his foot quickly and strongly turn his wrist in the manner of the inquartata in order to defend himself from your sword. In the same tempo that he passes, redisengage the sword under the hilt, lowering your vita as you see in the present figure so that you wound him in the face before he wounds you. In fact, while he carries his foot forward in order to pass it is not possible to parry. At times it is necessary to make the effect of this figure. Exercise well these two figures placed before.</p> | + | <p>This<ref>The two preceding figures.</ref> is one and the same counterdisengage at a distance against one who has their left foot forward and wants to pass by inquartata. I wanted to demonstrate to you with this figure the postures and wound so that it is possible to comprehend it well for the sake of necessity (when one is coming to bind you with their left foot forward). Stand in guard as you see in this figure, giving occasion to your enemy to throw at your chest. If he is a valiant man, he will pass with his foot quickly and strongly turn his wrist in the manner of the inquartata in order to defend himself from your sword. In the same tempo that he passes, redisengage the sword under the hilt, lowering your vita as you see in the present figure so that you wound him in the face before he wounds you. In fact, while he carries his foot forward in order to pass it is not possible to parry. At times it is necessary to make the effect of this figure. Exercise well these two figures placed before.</p> |

| rowspan="2" | | | rowspan="2" | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|68|lbl=48|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|69|lbl=49|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|68|lbl=48|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|69|lbl=49|p=1}} | ||

| Line 675: | Line 677: | ||

| <p>[52] '''Method of Playing with the Single Sword,''' while the enemy has sword and dagger</p> | | <p>[52] '''Method of Playing with the Single Sword,''' while the enemy has sword and dagger</p> | ||

| − | <p>With this figure I will demonstrate | + | <p>With this figure I will demonstrate parrying and wounding to you, you with the single sword against an enemy who has sword and dagger. You will stand with your right foot forward with a just pace, with your vita back, holding the sword forward ready to parry and wound when there is a tempo. It is necessary you not be first to throw because you will be in danger, since in throwing your enemy could parry your stoccata with the dagger and if he were a valiant man you would not be able to parry his. If you stay in guard as I have said above, ready to parry, showing fear of him so that he throws disconcerted. While he throws parry strongly with the forte of your sword and throw the stoccata at his face, because he will throw at you strongly and long and while throwing his dagger will remove itself so you can strike him safely. That given, immediately return backward outside of measure, holding your sword in his in the way described above. As many times as he throws, you will wound the same, taking care however not to throw at his chest, which would not be safe, since the one that has sword and dagger will be much bolder than one who finds themselves with the single sword, and thus thinking to give you as many stoccate as he likes, he will come to be disconcerted at throwing forward at you, not thinking of anything else. If you stand in guard with judgement you can parry safely and strongly and wound your enemy, always in the face, returning safely outside of measure with your sword over his. If your enemy were to disengage the sword to the inside, turn your wrist and parry and throw strongly as I have said.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/71|1|lbl=51}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/71|1|lbl=51}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/58|1|lbl=30}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/58|1|lbl=30}} | ||

| Line 682: | Line 684: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[53] If you see that he wants to fly upon you, | + | | <p>[53] If you see that he wants to fly upon you, pull yourself backward and throw at him in the tempo that he moves to come forward. If you were to find yourself in guard with your sword in his and he would like<ref>The original text is “vorreste”, or “you would like”. As our fencer’s opponent is the one with the dagger, it is likely that this is a mistake in the text</ref> to first parry with the dagger and then wound, in the tempo you see that he lowers the dagger in order to parry, immediately disengage the sword above the dagger in the way described in figure number [21].<ref>The figure number is missing in both the 1606 and 1628 printings. Jakob de Zeter’s 1619 German/French version refers to Figure 21.</ref> Immediately after return outside of measure with your sword over his.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/71|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/71|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/60|1|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/60|1|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 689: | Line 691: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| class="noline" | | | class="noline" | | ||

| − | | class="noline" | <p>[54] Take care, however, not to throw if he stays in guard if by chance you do not see some tempo that when you throw he cannot wound you, as described above when tempo and measure were discussed. If he | + | | class="noline" | <p>[54] Take care, however, not to throw if he stays in guard if by chance you do not see some tempo that when you throw he cannot wound you, as described above when tempo and measure were discussed. If he stands in guard waiting, either out of fear, or rather with art in order to deceive you, stay outside of measure with your sword over his and seek to parry and wound safely according to the occasion.</p> |

| class="noline" | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/71|3|lbl=-}} | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/71|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| class="noline" | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/60|2|lbl=-}} | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/60|2|lbl=-}} | ||

Revision as of 22:33, 14 July 2020

| Nicoletto Giganti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1550-1560 Fossombrone, Italy |

| Died | after 1622 Venice, Italy (?) |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Citizenship | Republic of Venice |

| Patron | Cosimo II de Medici |

| Influenced | Bondì di Mazo (?) |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) |

|

Nicoletto Giganti (Niccoletto, Nicolat; 1550s-after 1622[1]) was a 16th – 17th century Italian soldier and fencing master. He was likely born to a noble family in Fossombrone in central Italy,[2] and only later became a citizen of Venice as he stated on the title page of his 1606 treatise. Little is known of Giganti’s life, but in the dedication to his 1606 treatise he counts twenty seven years of professional experience (possibly referring to service in the Venetian military, a long tradition of the Giganti family).[3] The preface to his 1608 treatise describes him as a Mastro d'Arme of the Order of St. Stephen in Pisa, giving some further clues to his career.

In 1606, Giganti published a treatise on the use of the rapier (both single and with the dagger) titled Scola, overo teatro ("School or Theater"). This treatise is structured as a series of progressively more complex lessons, and Tom Leoni opines that this treatise is the best pedagogical work on rapier fencing of the early 17th century.[4] It is also the first treatise to fully articulate the principle of the lunge.

In 1608, Giganti made good on the promise in his first book that he would publish a second volume.[5] Titled Libro secondo di Niccoletto Giganti Venetiano, it covers the same weapons as the first as well as rapier and buckler, rapier and cloak, rapier and shield, single dagger, and mixed weapon encounters. This text in turn promises two additional works, on the dagger and on cutting with the rapier, but there is no record of these books ever being published.

While Giganti's second book quickly disappeared from history, his first seems to have been quite popular: reprints, mostly unauthorized, sprang up many times over the subsequent decades, both in the original Italian and, beginning in 1619, in French and German translations. This unauthorized dual-language edition also included book 2 of Salvator Fabris' 1606 treatise Lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme which, coupled with the loss of Giganti's true second book, is probably what has lead many later bibliographers to accuse Giganti himself of plagiarism.[6]

Contents

Treatise

Giganti, like many 17th century authors, had a tendency to write incredibly long, multi-page paragraphs which quickly become hard to follow. Jacques de Zeter's 1619 dual-language edition often breaks these up into more manageable chunks, and so his layout is reflected in these concordances.

Research on Giganti's newly-rediscovered second book is still ongoing, and it cannot yet be included in the tables below.

Images |

Italian (1606) |

German (1619) |

French (1619) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

School, or Theatre In which different manners and methods of parrying and wounding with the single sword and sword and dagger are represented; Where every scholar will be able to exercise and become practised in the profession of arms |

[i] SCOLA, OVERO TEATRO, Nelquale sono rappresentate diverse maniere, e modi di parare, e di ferire di Spada sola, e di Spada, e Pugnale; Dove ogni studioso potrà essercitarsi, & farsi prattico nella professione dell’Armi, |

|||

By Nicoletto Giganti, Venetian, To The Most Serene Don Cosmo De’ Medici Great Prince Of Tuscany |

DI NICOLETTO GIGANTI VINITIANO, AL SERENISS. D. COSMO DE’ MEDICI GRAN PRINCIPE DI TOSCANA. |

|||

With license and privilege of the Superiors In Venice |

Con licenza de’ Superiori, & Privilegio. IN VENETIA, |

|||

To the Most Serene Don Cosmo de Medici Great Prince of Tuscany my only Lord Just as iron extracted from the rough mines would be useless if it had not received shape suited to human armies from industrious art, thus the same in the hands of the strong soldier can be of little profit if, accompanied by studious and wise valour, the way is not made clear for every difficult and triumphant success. In this way to a point since the Good Shepherd welcomes the operation, because almost all the noblest things proceeding from our actions receive appropriate material from His hands, which, refined and dignified by the industry of the spirit, achieve miraculous and powerful effects. Now I say that this temperament is wonderfully demonstrated in the excellent and illustrious greatness of Your Most Serene Highness, who holds the natural greatnesses brought back to their peak from the invincible glorious works of your Ancestors, not only in the ancient and royal histories, but reflecting in yourself all the light of the present and past splendour, adorning them with your own virtues so that everyone admires the most divine tempers, and with wonderment says such a Most Serene Lord is no less fitting to that Most Serene State, than such a Most Serene State to that Most Serene Lord. But I will only say that this proposition, just as is demonstrated clearly in all the arts; so it is evidently perceived in exercising arms. Discussing the strength of iron, although it is exercised by a strong arm and agile body, if it is not tuned with observed rules and exercised study it is shown to be perilous and of little valour: Whereas if the art can be known by a wise captain, and he obeys it as a bold minister, they make marvelous prowess of it. You serve us as a clear example, who Heaven had to grant all height of perfect quality as in the most complete illumination of the present age. You who have in the noblest proportion stature, puissance, vigour joined to agility, promptness, and strength, in order to draw with your highest ingenuity the finesse of industry, advice, time, and art that can make you most a complete and Most Illustrious Captain, a Most Serene and most singular Prince. |

[iii] AL SERENISSIMO DON COSMO DE’ MEDICI GRAN PRINCIPE DI TOSCANA unico mio Signore. SI come il ferro dalle rigide minere sotratto inutile riuscirebbe, se dall’arte industre non riceveste forma accommodata a gli essercitii humani: Così l’istesso nelle mani del forte soldato riesce di poco frutto, se da studioso, & accorto valore accompagnato non s’apre la strada ad ogni difficile, & vittorioso successo. In questo modo a punto, perche, l’eterno fattore si compiace di operare. Perche [iv] quasi tutte le più nobil cose, procedenti da gli effetti nostri ricevono accomodata materia dalle sue mani, la quale poi raffinata, & illustrata dall’industria dell’animo fà riuscire effetti mirabili, e postenti. Taccio hora che questo temperamento meravigliosamente si dimostri nell’Eccelse, & illustri grandezze di Vostra Altezza Sereniss. la quale, non solo nelli antichi, & regii annali tiene le naturali grandezze ridotte al colmo da invitte opre gloriose de gli Avi suoi, ma in se stessa reflettendo tutto il lume del presente, & del passato splendore così gli adorna con le proprie virtudi , che ogn’un ammira le divinissime tempre, & con stupore dice non meno convenirsi tal Sereniss. Signore a quel Sereniss. Stato, che tal Serenissimo Stato a quel Serenissimo Signore: Ma dirò solo, che il detto proposto, si come in tutte le arti si dimostra chiaro; così si scerne evidentemente nell’armeggiare, & trattar la forza del ferro, il quale benche da forte braccio, & agil corpo sia essercitato, se però con osservate regole, & essercitato studio non vien accordato, e periglioso si mostra, e di poco valore: Ove, che se la possa riconosce l’arte per duce accorta, e le obedisce come ministra ardita, ne riescono meravigliose prodezze. Ci serve per essempio chiaro il testimonio di lei, nella qual dovendo il Ciel accordare ogni colmo di perfetta qualità come in compitissimo lume dell’età presente, hà in nobilissima proportione di statura, di poderosità, di fangue congionta l’agilità, la prontezza, la forza, per trarne con l’altissimo ingegno suo la finezza dell’industria, [v] dell’aviso, del tempo, e dell’arte, che possono far compitissimo & Illustrissimo Capitano un Serenissimo, & singolarissimo Principe. |

|||

Wherefore I, recognizing and admiring with humblest affection the mature splendour of your newly made and happy years, and reading in the face of the world the secure hopes and fruits of the future age, adoring that hand from which Italy and the entire world is taking safe rest and glorious protection, to that I offer and consecrate with humble dedication this small, I will certainly not say fruit, but work of my labours. Therefore, it only must please you, being of material welcomed by you which deigns to bend your Most Serene eye. To that end, let many of your highest rays pass over where the baseness of my ingenuity with the exercise of this art that I have dealt with for 27 years does not arrive. Let this work, in itself humble, present itself happily to the view of the World. It will be effected with the action of my devotion, together with the fruit of your Most Serene mercy, who serving being the full glory, I pray that Heaven makes me a worthy, even lowest servant. In Venice February 10, 1606.

|

Onde io riconoscendo, & ammirando con humilissimo affetto il maturo splendore de gli freschi, & felici anni suoi; & legendo nella fronte del mondo le sicure speranze, & frutti dell’età futura; Adorando quella mano dalla quale l’Italia, e il Mondo tutto, è per prender sicuro riposo, e gloriosa protettione; a quella porgo, e consacro con humil dedicatione questo poco non dirò già frutto, ma fatica delle mie fatiche, che perciò solo le doverà gradire, essendo di materia da lei gradita; Nel quale si degnerà piegar l’occhio suo Serenissimo, acciò , ove la bassezza del mio ingegno con l’esercitio di quest’arte, che per anni 27. vò trattando, non arriva; trapassi tanti del suo altissimo raggio, che facci comparire l’opra in se humile, felicemente alla vista del Mondo; & sarà insieme effetto della mia devotione, & frutto della Sereniss. benignità sua, Alla qual essendo somma gloria il servire, pregherò il Cielo che mi facci degno, benche infimo servitore. Di Venetia a’ 10. Febraro 1606.

|

|||

To the Lord Readers, Almoro Lombardo, Son of the Most Renowned Lord Marco. Wanting to write on the matter of arms, although the author does not mention that it is a science, to me it appears a necessary thing, Lord Readers, to treat with what share it has, and of which name it would adorn itself so that everyone knows its greatness, dignity, and privilege. Whereupon first some students of this this most noble science read and discuss the most learned and easy observations of this valorous and knowledgeable professor Nicoletto Giganti, I, by observing the rule and general precept of a person who wants to address anything, will come to the definition, and then to the general division of this word Science, from which it will be possible for two things to finally be recognized by everyone, showing us that this beautiful profession is science. Science, therefore, is a certain and manifest knowledge of things that the intellect acquires. It is of two sorts, that is, Speculative and Practical. Speculative is a simple operation of the intellect around its own object. Practical only consists in the actual workings of the intellect. Speculative is divided in two parts, that is, in Real Speculation and Rational Speculation. The Real aims at the reality of its object, which demonstrates its essence on its exterior. The Rational consists of those things that only the intellect administers and does not extend itself to other goals. Physics is a Real Speculative Science that only aims at moving and natural things, like the elements. Mathematics is a Real Speculative Science that only extends itself to continuous and discrete quantity. Continuous like lines, circles, surfaces, the measures of which deal with Arithmetic. Grammar, Rhetoric, Poetry, and Logic are Rational Speculative Sciences. Practical Science is divided in two: Active and Workable. Active is Ethics, Politics, and Economics. Workable can be divided in seven others, called mechanical, which are these: Woolcraft, Agriculture, Soldiery, Navigation, Medicine, Hunting, and Metalworking. Now, coming to what I promised above about this noble science, I will go over its qualities and nature, discussing whether it is Speculative or Practical science. In my opinion I say that it is Speculative, and prove it with diverse reasons. That it is science there is no doubt, because it is not acquired if it is not mediated by the operation of the intellect, from which it is born. That it is Speculative is certain since it does not consist in anything other than simple knowledge of its object, as I will be discussing below. The object of this science is nothing more than parrying and wounding. The knowledge of those two things is a work of the intellect, and moreover with intelligence professors of this science do not extend it further than the knowledge of them, which cannot be understood at all unless one first has knowledge of tempi and measures, or rather, knowledge of Feint, Disengage, or resolution without knowledge of tempi and measures. These are all operations of the intellect, and moreover outside of this knowledge the intellect does not extend, because as I have said the aim of these professions is understanding parrying. We will see if it is Real Speculative or Rational Speculative. Considering this, it cannot be Rational, and the reason is this: because if it is indeed an operation of the intellect, nevertheless it spreads further, wherefore I find it to be Real Speculative. Real, because the knowledge of its aim is shown to us outwardly by the intellect. As the understanding of wounding and parrying, with tempi, measures, feints, disengages, and resolutions, even though they are operations of the intellect, they cannot be understood if not outwardly, and this exterior consists in the bearing of the body and of the Sword in the guards and counterguards, which all consist of circles, angles, lines, surfaces, measures, and of numbers.' These things, which must be observed, can be read about in Camillo Agrippa and in many other professors of this science. Note that just as those operations of the intellect without an exterior operation cannot be shown, so these exterior operations cannot be understood without the operations of the intellect first, in a manner that this science, which derives from the intellect, cannot be understood if not outwardly. Neither can one understand outwardly without operations of the intellect. These operations seek to understand the greatness, excellence, and perfection of this profession, and always come united. As there can never be Sun without day, nor day without Sun, never will there be those without these, nor these without those. In the end we see that it is Real Speculative Science. This science of the Sword, or of arms, is a Real Speculative Mathematic Science, and Geometric, and Arithmetic. Geometric because it consists in lines, circles, angles, surfaces, and measures. Arithmetic because it consists of numbers. There is no motion of the body that does not make an angle or constraint. There is no motion of the Sword that does not travel in a line. There is neither guard nor counterguard that does not go by the number. The observations of these things all depend on knowledge of tempi and measures, whence I conclude that this most noble science is Real, Mathematic, Geometric, and Arithmetic, as I said a little above. |

[vii] ALLI SIG. LETTORI, ALMORO LOMBARDO fù del Clarissimo Signor Marco. VOLENDOSI scrivere nella meteria dell’armi, benche l’auttore non facci mentione, che scentia ella si sia, pur à me pare cosa necessaria, ò Signori Lettori di trattare che parte ella habbia, & di qual nome ella s’adorni, & ciò perche ciascuno conosca quale sia la grandezza, la dignità & il privilegio suo. La onde prima che alcuno studioso di questa nobilissima scienza legga, & discorra le dottissime, e facilissime osservationi di questo valoroso, & intendente professore Nicoletto Gigantil io per osservare la regola, & il precetto generale di chi vuole trattare di cosa alcuna, verrò alla diffinitione, & poi alla divisione generale di questa voce Scienza, dalle quali due cose finalmente potrà venire in consideratione à ciascuno, che scienza questa bella professione ci mostri. La Scienza adunque è una certa, & manifesta cognitione delle cose, che l’intelletto acquista: & questa è di due sorti, cioè Speculativa, & Prattica. La Speculativa è una semplice operatione dell’intelletto circa il suo proprio oggetto. La Prattica solo consiste nelle attuali operationi dell’intelletto. La Speculativa si divide in due parti, cioè in Speculativa reale, & in Speculativa rationale. La reale mira alla realtà dell’oggetto suo, il quale dimo- [viii] stra nell’esteriore l’essentia sua. La rationale consiste intorno à quelle cose, che solo l’intelletto gli somministra, nè più in oltre vuole, che l’esser suo s’estenda. La Fisica è una scienza reale speculativa, che solo mira alle cose mobili, e naturali, come à gli elementi. La matematica è una scienza Speculativa reale, che solo estende l’esser suo in quanto continuo e discreto; continuo come intorno alle linee, à i circoli, alle superficie; & le misure di questa tratta l’Arithmetica. La Grammatica, la Retorica, la Poesia, la Logica sono scienze speculative rationali. La Scientia prattica, si divide ancor ella in due, in Attiva, e Fattiva; Attiva è l’Etica, la Politica, e l’Economica; la Fattiva poi si divide in sette altre, le quali si chiamano mechaniche, e sono queste il Lanificio, l’Agricoltura, il Soldato mercenario, la Navigatione, la Medicina, la Caccia, e l’arte Fabrile. Hora per venire a quello c’ho di sopra promesso circa a questa nobil scienza, andrò sopra le qualità, e la natura sua discorrendo, cioè s’ella sia scientia Speculativa, o Prattica. Io per opinione mia dico, & lo provo con diverse ragioni ch’ella è Speculativa. Et che sii scienza non v’è dubio alcuno, perche questa non s’acquista se non mediante l’operatione dell’intelletto, dalla quale essa nasce; ch’ella sia Speculativa è cosa certa poiche non tonsiste in altro, che nella semplice cognitione dell’oggetto suo, come andrò mostrando più a basso: Et l’oggetto di questa scienza altro non è, che il riparare, & il ferire; il saper delle quali due cose, è opera dell’intelletto; nè il professore di questa scienza più in oltre s’estende con l’ingegno, che nella cognitione di queste due cose, lequali non potrà alcuno sapere se prima non havrà la cognitione de’ tempi, e delle misure, ò di Finte, ò di Cavatione, ò di risolutioni senza cognitione de’ tempi, e delle misure, & queste sono tutte operationi dell’intelletto, & fuori di questa cognitione l’intelletto non s’estende più in oltre; perche come ho detto il fine di queste professione è saper riparare; ma vediamo s’ella sÿ speculativa reale, ò speculativa rationale. Io vado considerando, che rationale non può essere, & la ragione è que- [ix] sta, perche se ben ella è operatione dell’intelletto; nondimeno più in oltre si diffonde; perilche trovo ella esser speculativa reale. Reale, perche la cognitione del suo fine ci vien mostrata dall’intelletto esteriormente; poiche il saper ferire, & il saper riparare con i tempi, con le misure, finte, cavationi, e risolutioni, benche siano operationi dell’intelletto, non perciò si possono conoscere, se non esteriormente, e questo esteriore consiste nel portamento del corpo, & della Spada nelle guardie, e nelle contraguardie, ilche tutto consiste ne i circoli, negli angoli, nelle linee, nelle superficie, nelle misure, e ne i numeri; lequali cose, come che s’habbino à osservare, si potrà leggere in Camillo Agrippa, & in molti altri professori di questa scienza. Ma notate, che si come quelle operationi dell’intelletto senza una operatione esteriore non si possono mostrare: così queste operationi esteriori non si possono conoscere senza le prime operationi dell’intelletto, in maniera che questa scienza non si può conoscere, che derivi dall’intelletto, se non esteriormente; nè si può conoscere esteriormente senza operatione dell’intelletto, le quali operationi à voler conoscere la grandezza, eccellenza, e perfettione di questa professione, sempre si vedranno unite; e come non sarà mai Sole senza giorno, nè giorno senza Sole, non saranno mai quelle senza queste, nè queste senza quelle. Resta che noi vediamo, che scienza Speculativa reale ella sia. Questa scienza della Spada, ò dell’armi, è una scienza Speculativa real Mathematica, & è di Geometria, & Arithmetica; di Geometria perche consiste in linee, circoli, angoli, superficie, e misure. Di Arithmetica, perche consiste in numeri; non è moto del corpo, che non facci angolo, o vincolo; non è moto della Spada, che non camini per linea; non è guardia, nè contraguardia, che non vadi per numero; l’osservationi delle quali cose tutte dipendono dalla cognitione de’ tempi, e delle misure; onde concludo, che questa nobilissima scienza sia Speculativa reale Mathematica, di Geometria, & Arithmetica, come poco di sopra hò detto. |

|||