|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Giacomo di Grassi"

(→Temp) |

|||

| Line 2,691: | Line 2,691: | ||

{{master end}} | {{master end}} | ||

| − | |||

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| title = Physical Training | | title = Physical Training | ||

| Line 2,705: | Line 2,704: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | ''' | + | | <p>'''How a man by private practice may obtain strength of body thereby'''</p> |

| − | If nature had bestowed strength upon men (as many believe) in such sort as she has given sight, hearing and other senses, which are such in us, that they may not by our endeavor either be increased, or diminished, it should be no less superfluous, than ridiculous to teach how strength should be obtained, than it were if one should say, he would instruct a man how to hear or see better than he does already by nature. Neither albeit he that becomes a Painter or a Musician sees the proportions much better than he did before, or by hearing learns the harmony and conformity of voices which he knew not, ought it therefore be said, that he sees or hears more than he did? For that proceeds not of better hearing or seeing, but of seeing and hearing with more reason. But in strength it does not so come to pass: For it is manifestly seen, that a man of ripe age and strength, cannot lift up a weight today which he cannot do on the morrow, or some other time. But contrary, if a man prove with the self same sight on the morrow or some other time to see a thing which yesterday he saw not in the same distance, he shall but trouble himself in vain, and be in danger rather to see less than more, as it commonly happen to students and other such, who do much exercise their sight. Therefore there is no doubt at all but that a mans strength may be increased by reasonable exercise, And so likewise by too much rest it may be diminished: the which if it were not manifest, yet it might be proved by infinite examples. You shall see Gentlemen, Knights and others, to bee most strong and nimble in running or leaping, or in vaulting, or in turning on Horseback, and yet are not able by a great deal to bear so great a burden as a Country man or Porter: But in contrary in running and leaping, the Porter and Country man are most slow and heavy, neither know how to vault upon their horse without a ladder. And this proceeds of no other cause, than for that every man is not exercised in that which is most esteemed: So that if in the managing of these weapons, a man would get strength, it shallbe convenient for him to exercise himself in such sort as shallbe declared. | + | |

| + | <p>If nature had bestowed strength upon men (as many believe) in such sort as she has given sight, hearing and other senses, which are such in us, that they may not by our endeavor either be increased, or diminished, it should be no less superfluous, than ridiculous to teach how strength should be obtained, than it were if one should say, he would instruct a man how to hear or see better than he does already by nature. Neither albeit he that becomes a Painter or a Musician sees the proportions much better than he did before, or by hearing learns the harmony and conformity of voices which he knew not, ought it therefore be said, that he sees or hears more than he did? For that proceeds not of better hearing or seeing, but of seeing and hearing with more reason. But in strength it does not so come to pass: For it is manifestly seen, that a man of ripe age and strength, cannot lift up a weight today which he cannot do on the morrow, or some other time. But contrary, if a man prove with the self same sight on the morrow or some other time to see a thing which yesterday he saw not in the same distance, he shall but trouble himself in vain, and be in danger rather to see less than more, as it commonly happen to students and other such, who do much exercise their sight. Therefore there is no doubt at all but that a mans strength may be increased by reasonable exercise, And so likewise by too much rest it may be diminished: the which if it were not manifest, yet it might be proved by infinite examples. You shall see Gentlemen, Knights and others, to bee most strong and nimble in running or leaping, or in vaulting, or in turning on Horseback, and yet are not able by a great deal to bear so great a burden as a Country man or Porter: But in contrary in running and leaping, the Porter and Country man are most slow and heavy, neither know how to vault upon their horse without a ladder. And this proceeds of no other cause, than for that every man is not exercised in that which is most esteemed: So that if in the managing of these weapons, a man would get strength, it shallbe convenient for him to exercise himself in such sort as shallbe declared.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/177|4|lbl=165|p=1}} {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/178|1|lbl=166|p=1}} |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | For the obtaining of this strength and activity, three things ought to be considered, to wit, the arms, the feet and the legs, in each of which it is requisite that every one be greatly exercised, considering that to know well how to manage the arms, and yet to be ignorant in the motion of the feet, wanting skill how to go forwards and retire backwards, causes men oftentimes to overthrow themselves. | + | | <p>For the obtaining of this strength and activity, three things ought to be considered, to wit, the arms, the feet and the legs, in each of which it is requisite that every one be greatly exercised, considering that to know well how to manage the arms, and yet to be ignorant in the motion of the feet, wanting skill how to go forwards and retire backwards, causes men oftentimes to overthrow themselves.</p> |

| + | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/178|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/179|1|lbl=167|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | And on the other side, when one is exercised in the governing of his feet, but is ignorant in the timely motion of his arms, it falls out that he goes forwards in time, but yet wanting skill how to move his arms, he does not only not offend the enemy, but also many times remains hurt and offended himself. The body also by great reason ought to be borne and sustained upon his foundation. For when it bows either too much backwards or forwards, either on the one or the other side, straight way the government of the arms and legs are frustrated and the body, will or nil, remains stricken. Therefore I will declare the manner first how to exercise the Arms, secondly the Feet, thirdly the Body, Feet and Arms, jointly: | + | | <p>And on the other side, when one is exercised in the governing of his feet, but is ignorant in the timely motion of his arms, it falls out that he goes forwards in time, but yet wanting skill how to move his arms, he does not only not offend the enemy, but also many times remains hurt and offended himself. The body also by great reason ought to be borne and sustained upon his foundation. For when it bows either too much backwards or forwards, either on the one or the other side, straight way the government of the arms and legs are frustrated and the body, will or nil, remains stricken. Therefore I will declare the manner first how to exercise the Arms, secondly the Feet, thirdly the Body, Feet and Arms, jointly:</p> |

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/179|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | ''' | + | | <p>'''Of the exercise and strength of the arms''' |

| − | Let a man be never so strong and lusty, yet he shall deliver a blow more slow and with less force than another shall who is less strong, but more exercised: and without doubt he shall so weary his arms, hands and body, that he cannot long endure to labor in any such business. And there has been many, who by reason of such sudden weariness, have suddenly despaired of themselves, giving over the exercise of the weapon, as not appertaining unto them. Wherein they deceive themselves, for such weariness is vanquished by exercise, by means whereof it is not long, but that the body feet and arms are so strengthened, that heavy things seem light, and that they are able to handle very nimbly any kind of weapon, and in brief overcome all kind of difficulty and hardness. Therefore when one would exercise his arms, to the intent to get strength, he must endeavor continually to overcome weariness, resolving himself in his judgment, that pains is not caused, through debility of nature, but rather hangs about him, because he has not accustomed to exercise his members thereunto. | + | |

| + | <p>Let a man be never so strong and lusty, yet he shall deliver a blow more slow and with less force than another shall who is less strong, but more exercised: and without doubt he shall so weary his arms, hands and body, that he cannot long endure to labor in any such business. And there has been many, who by reason of such sudden weariness, have suddenly despaired of themselves, giving over the exercise of the weapon, as not appertaining unto them. Wherein they deceive themselves, for such weariness is vanquished by exercise, by means whereof it is not long, but that the body feet and arms are so strengthened, that heavy things seem light, and that they are able to handle very nimbly any kind of weapon, and in brief overcome all kind of difficulty and hardness. Therefore when one would exercise his arms, to the intent to get strength, he must endeavor continually to overcome weariness, resolving himself in his judgment, that pains is not caused, through debility of nature, but rather hangs about him, because he has not accustomed to exercise his members thereunto.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/179|3|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/180|1|lbl=168|p=1}} |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

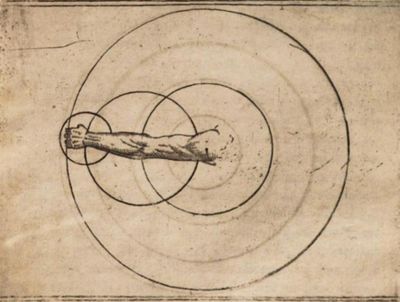

| − | | There are two things to be considered in this exercise, to wit the hand that moves, and the thing that is moved, which two things being orderly laid down, I hope I shall obtain as much as I desire. As touching the hand and the treatise of the true Art, in three parts, that is to say, into the wrist, the elbow, and the shoulder, In every of the which it is requisite, that it move most swiftly and strongly, regarding always in his motion the quality of the weapon that is borne in the hand, the which may be infinite, and therefore I will leave them and speak only of the single sword, because it bears a certain proportion and agreement unto all the rest. | + | | <p>There are two things to be considered in this exercise, to wit the hand that moves, and the thing that is moved, which two things being orderly laid down, I hope I shall obtain as much as I desire. As touching the hand and the treatise of the true Art, in three parts, that is to say, into the wrist, the elbow, and the shoulder, In every of the which it is requisite, that it move most swiftly and strongly, regarding always in his motion the quality of the weapon that is borne in the hand, the which may be infinite, and therefore I will leave them and speak only of the single sword, because it bears a certain proportion and agreement unto all the rest.</p> |

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/180|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | The sword as each man knows, strikes either with the point or with the edge. To strike edgewise, it is required that a man accustom himself to strike edgewise as well right as reversed with some cudgel or other thing apt for the purpose, First practicing to fetch the compass of the shoulder, which is the strongest, and yet the slowest edgeblow that may be given: Next and presently after, the compass of the elbow, then that of the wrist, which is more prest and ready then any of the rest. After certain days that he has exercised these three kinds of compassing edgeblows one after another as swiftly as he may possible And when he feels in himself that he has as it were unloosed all those knittings or joints of the arm, and can strike and deliver strongly from two of these joints, to wit the Elbow and the Wrist, he shall then let the Shoulder joint stand, and accustom to strike strongly and swiftly with those two of the El bow and the Wrist, yet at the length and in the end of all shall only in a manner practice that of the Wrist, when he perceives his hand and wrist to be well strengthened, delivering this blow of the Wrist, twice or thrice, sometimes right, sometimes reversed, once right, and once reversed, two reverses and one right, and likewise, two right and one reversed, to the end that the handle take not accustom to deliver a right blow immediately after a reverse. For sometimes it is commodious, and does much advantage a man to deliver two right, and two reversed, or else after two right, one reversed: and these blows, ought to be exercised, as well with one hand as with the other, standing steadfast in one reasonable pace, practicing them now, aloft, now beneath, now in the middle. As touching the weight or heft, which is borne in the hand, be it sword or other weapon, I commend not their opinion any way, who will for the strengthening of a man's arm that he handle first a heavy weapon, because being first used to them, afterwards, ordinary weapons will seem the lighter unto him, but I think rather the contrary, to wit, that first to the end, he does not over burden and choke his strength, he handle a very light sword, and such a one, that he may most nimbly move. For the end of this art is not to lift up or bear great burdens, but to move swiftly. And there is no doubt but he vanquishes which is most nimble, and this nimbleness is not obtained by handling of great hefts or weights, but by often moving. | + | | <p>The sword as each man knows, strikes either with the point or with the edge. To strike edgewise, it is required that a man accustom himself to strike edgewise as well right as reversed with some cudgel or other thing apt for the purpose, First practicing to fetch the compass of the shoulder, which is the strongest, and yet the slowest edgeblow that may be given: Next and presently after, the compass of the elbow, then that of the wrist, which is more prest and ready then any of the rest. After certain days that he has exercised these three kinds of compassing edgeblows one after another as swiftly as he may possible And when he feels in himself that he has as it were unloosed all those knittings or joints of the arm, and can strike and deliver strongly from two of these joints, to wit the Elbow and the Wrist, he shall then let the Shoulder joint stand, and accustom to strike strongly and swiftly with those two of the El bow and the Wrist, yet at the length and in the end of all shall only in a manner practice that of the Wrist, when he perceives his hand and wrist to be well strengthened, delivering this blow of the Wrist, twice or thrice, sometimes right, sometimes reversed, once right, and once reversed, two reverses and one right, and likewise, two right and one reversed, to the end that the handle take not accustom to deliver a right blow immediately after a reverse. For sometimes it is commodious, and does much advantage a man to deliver two right, and two reversed, or else after two right, one reversed: and these blows, ought to be exercised, as well with one hand as with the other, standing steadfast in one reasonable pace, practicing them now, aloft, now beneath, now in the middle. As touching the weight or heft, which is borne in the hand, be it sword or other weapon, I commend not their opinion any way, who will for the strengthening of a man's arm that he handle first a heavy weapon, because being first used to them, afterwards, ordinary weapons will seem the lighter unto him, but I think rather the contrary, to wit, that first to the end, he does not over burden and choke his strength, he handle a very light sword, and such a one, that he may most nimbly move. For the end of this art is not to lift up or bear great burdens, but to move swiftly. And there is no doubt but he vanquishes which is most nimble, and this nimbleness is not obtained by handling of great hefts or weights, but by often moving.</p> |

| + | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/180|3|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/181|1|lbl=169|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | But yet after he has sometime travailed with a light weapon, then it is necessary according as he feels himself to increase in strength of arm, that he take another in hand, that is something heavier, and such a one as will put him to a little more pain, but yet not so much, that his swiftness in motion be hindered thereby. And as his strength increases, to increase likewise the weight by little and little. So it will not be long, but that he shall be able to manage very nimbly any heavy sword. The blow of the point or thrust, cannot be handled without the consideration of the feet and body, because the strong delivering of a thrust, consists in the apt and timely motion of the arms feet and body: For the exercise of which it is necessary that he know how to place them in every of the three wards, to the end, that from the ward he may deliver strongly a thrust in as little time as possible. And therefore he shall take heed that in the low ward, he make a reasonable pace, bearing his hand without his knee, forcing one the thrust nimbly, and retiring his arm backward, and somewhat increasing his forefoot more forwards, to the end, the thrust may reach the farther: But if he chance to increase the forefoot a little too much, so that the breadth thereof be painful unto him, than for the avoiding of inconveniences, he shall draw his hind foot so much after, as he did before increase the forefoot. And this thrust must be oftentimes jerked or sprung forth, to the end to lengthen the arm, accustoming to drive it on without retiring of itself, that by that means it may the more readily settle in the broad ward, For that is framed (as it is well known) with the arm and foot widened outwards, but not lengthened towards the enemy. And in thrusting let him see, that he deliver them as straight as he can possibly, to the end, they may reach out the longer. | + | | <p>But yet after he has sometime travailed with a light weapon, then it is necessary according as he feels himself to increase in strength of arm, that he take another in hand, that is something heavier, and such a one as will put him to a little more pain, but yet not so much, that his swiftness in motion be hindered thereby. And as his strength increases, to increase likewise the weight by little and little. So it will not be long, but that he shall be able to manage very nimbly any heavy sword. The blow of the point or thrust, cannot be handled without the consideration of the feet and body, because the strong delivering of a thrust, consists in the apt and timely motion of the arms feet and body: For the exercise of which it is necessary that he know how to place them in every of the three wards, to the end, that from the ward he may deliver strongly a thrust in as little time as possible. And therefore he shall take heed that in the low ward, he make a reasonable pace, bearing his hand without his knee, forcing one the thrust nimbly, and retiring his arm backward, and somewhat increasing his forefoot more forwards, to the end, the thrust may reach the farther: But if he chance to increase the forefoot a little too much, so that the breadth thereof be painful unto him, than for the avoiding of inconveniences, he shall draw his hind foot so much after, as he did before increase the forefoot. And this thrust must be oftentimes jerked or sprung forth, to the end to lengthen the arm, accustoming to drive it on without retiring of itself, that by that means it may the more readily settle in the broad ward, For that is framed (as it is well known) with the arm and foot widened outwards, but not lengthened towards the enemy. And in thrusting let him see, that he deliver them as straight as he can possibly, to the end, they may reach out the longer.</p> |

| + | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/181|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/182|1|lbl=170|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | At what time one would deliver a thrust, it is requisite that he move the body and feet behind, so much in a compass, that both the shoulders, arm, and feet, be under one self same straight line. Thus exercising himself he shall deliver a very great and strong thrust. And this manner of thrusting ought oftentimes to be practiced, accustoming the body and feet (as before) to move in a compass: for this motion is that which instructs one, how he shall void his body. The thrust of the high ward is hardest of all other, not of itself, but because it seems that the high ward (especially with the right foot before) is very painful. And because there are few who have the skill to place themselves as they ought to deliver the thrust in as little time as is possible. The first care therefore in this so to place himself, that he stand steadily. And the site thereof is in this manner, to wit: To stand with the arm aloft, and as right over the body as is possible, to the end he may force on the thrust without drawing back of the arm or loosing of time. And whilst the arm is borne straight on high (to the end it may be borne the more straight, and with less pains) the feet also would stand close and united together, and that because, this ward is rather to strike than to defend, and therefore it is necessary that it have his increase prepared: so that when the thrust is discharged, he ought therewithall to increase the forefoot so much that it make a reasonable pace, and then to let fall the hand down to the low ward, from the which if he would depart again, and offend to the high ward, he must also retire his forefoot, near unto the hind foot, or else the hind foot to the forefoot, And in this manner he shall practice to deliver his thrust oftentimes always placing himself in this high ward with his feet united, discharging the thrust with the increase of the fore foot. But when it seems tedious and painful to frame this ward, then he must use, for the lengthening of his arm, to fasten his hand and take holdfast on some nook or staff, that stands out in a wall, as high as he may lift up his arm, turning his hand as if he held a sword, for this shall help very much to strengthen his arm, and make his body apt to stand at this ward. Now when he has applied this exercise, for a reasonable time, so that he may perceive by himself that he is nimble and active in delivering these blows and thrusts simply by themselves, then he shall practice to compound them, that is to say, after a thrust to deliver a right blow from the wrist, then a reverse, and after that another thrust, always remembering when he delivers a blow, from the wrist, after a thrust to compass his hind foot, to the end, the blow may be the longer: And when, after his right blow, he would discharge a reverse, he must increase a slope pace, that presently after it, he may by the increase of a straight pace, force on a strong thrust underneath. And so to exercise himself to deliver many of those orderly blows together, but yet always with the true motion of the feet and body, and with great nimbleness, and in as short time as possible, taking always for a most sure and certain rule, that he move the arms and feet, keeping his body firm and steadfast, so that it go not beastly forward, (and especially the head being a member of so great importance) but to keep always his body bowed rather backward than forward, neither to turn it but only in a compass to void blows and thrusts. | + | | <p>At what time one would deliver a thrust, it is requisite that he move the body and feet behind, so much in a compass, that both the shoulders, arm, and feet, be under one self same straight line. Thus exercising himself he shall deliver a very great and strong thrust. And this manner of thrusting ought oftentimes to be practiced, accustoming the body and feet (as before) to move in a compass: for this motion is that which instructs one, how he shall void his body. The thrust of the high ward is hardest of all other, not of itself, but because it seems that the high ward (especially with the right foot before) is very painful. And because there are few who have the skill to place themselves as they ought to deliver the thrust in as little time as is possible. The first care therefore in this so to place himself, that he stand steadily. And the site thereof is in this manner, to wit: To stand with the arm aloft, and as right over the body as is possible, to the end he may force on the thrust without drawing back of the arm or loosing of time. And whilst the arm is borne straight on high (to the end it may be borne the more straight, and with less pains) the feet also would stand close and united together, and that because, this ward is rather to strike than to defend, and therefore it is necessary that it have his increase prepared: so that when the thrust is discharged, he ought therewithall to increase the forefoot so much that it make a reasonable pace, and then to let fall the hand down to the low ward, from the which if he would depart again, and offend to the high ward, he must also retire his forefoot, near unto the hind foot, or else the hind foot to the forefoot, And in this manner he shall practice to deliver his thrust oftentimes always placing himself in this high ward with his feet united, discharging the thrust with the increase of the fore foot. But when it seems tedious and painful to frame this ward, then he must use, for the lengthening of his arm, to fasten his hand and take holdfast on some nook or staff, that stands out in a wall, as high as he may lift up his arm, turning his hand as if he held a sword, for this shall help very much to strengthen his arm, and make his body apt to stand at this ward. Now when he has applied this exercise, for a reasonable time, so that he may perceive by himself that he is nimble and active in delivering these blows and thrusts simply by themselves, then he shall practice to compound them, that is to say, after a thrust to deliver a right blow from the wrist, then a reverse, and after that another thrust, always remembering when he delivers a blow, from the wrist, after a thrust to compass his hind foot, to the end, the blow may be the longer: And when, after his right blow, he would discharge a reverse, he must increase a slope pace, that presently after it, he may by the increase of a straight pace, force on a strong thrust underneath. And so to exercise himself to deliver many of those orderly blows together, but yet always with the true motion of the feet and body, and with great nimbleness, and in as short time as possible, taking always for a most sure and certain rule, that he move the arms and feet, keeping his body firm and steadfast, so that it go not beastly forward, (and especially the head being a member of so great importance) but to keep always his body bowed rather backward than forward, neither to turn it but only in a compass to void blows and thrusts.</p> |

| + | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/182|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/183|1|lbl=171|p=1}} {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/184|1|lbl=172|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | Moreover, it shall not be amiss, after he has learned to strike, (to the end to strengthen his arms) if he cause another to force at him, either with a cudgel, or some other heavy thing, both edgeblows and thrusts, and that he encounter and sustain them with a sword, and ward thrusts by avoiding his body, and by increasing forwards. And likewise under edgeblows, either strike before they light, or else encounter them on their first parts, with the increase of a pace, that thereby he may be the more ready to deliver a thrust, and more easily sustain the blow. Farther, when he shall perceive, that he has conveniently qualified and strengthened this instrument of his body, it shall remain, that he only have recourse in his mind to the five advertisements, by the which a man obtains judgment. And that next, he order and govern his motions according to the learning and meaning of those rules. And afterwards take advise of himself how to strike and defend, knowing the advantage in every particular blow. And there is not doubt at all, but by this order he shall attain to that perfection in this Art which he desires. | + | | <p>Moreover, it shall not be amiss, after he has learned to strike, (to the end to strengthen his arms) if he cause another to force at him, either with a cudgel, or some other heavy thing, both edgeblows and thrusts, and that he encounter and sustain them with a sword, and ward thrusts by avoiding his body, and by increasing forwards. And likewise under edgeblows, either strike before they light, or else encounter them on their first parts, with the increase of a pace, that thereby he may be the more ready to deliver a thrust, and more easily sustain the blow. Farther, when he shall perceive, that he has conveniently qualified and strengthened this instrument of his body, it shall remain, that he only have recourse in his mind to the five advertisements, by the which a man obtains judgment. And that next, he order and govern his motions according to the learning and meaning of those rules. And afterwards take advise of himself how to strike and defend, knowing the advantage in every particular blow. And there is not doubt at all, but by this order he shall attain to that perfection in this Art which he desires.</p> |

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/184|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| class="noline" | | | class="noline" | | ||

| − | | class="noline" | ''' | + | | class="noline" | <p>'''Finished'''</p> |

| class="noline" | | | class="noline" | | ||

| − | | class="noline" | | + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf/184|3|lbl=-}} |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,800: | Line 2,805: | ||

{{sourcebox | {{sourcebox | ||

| work = English Transcription | | work = English Transcription | ||

| − | | authors = Early English Books Online | + | | authors = [[Early English Books Online]] |

| source link = | | source link = | ||

| source title= [[Index talk:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf|Index talk:DiGrassi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi)]] | | source title= [[Index talk:DiGraſsi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi) 1594.pdf|Index talk:DiGrassi his true Arte of Defence (Giacomo di Grassi)]] | ||

Revision as of 17:37, 12 June 2020

|

Caution: Scribes at Work This article is in the process of updates, expansion, or major restructuring. Please forgive any broken features or formatting errors while these changes are underway. To help avoid edit conflicts, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. Stay tuned for the announcement of the revised content! This article was last edited by Michael Chidester (talk| contribs) at 17:37, 12 June 2020 (UTC). (Update) |

| Giacomo di Grassi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 16th century Modena, Italy |

| Died | after 1594 London, England |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | |

| Notable work(s) | Ragione di adoprar sicuramente l'Arme (1570) |

| First printed english edition |

His True Arte of Defence (1594) |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | Český Překlad |

Giacomo di Grassi was a 16th century Italian fencing master. Little is known about the life of this master, but he seems to have been born in Modena, Italy and acquired some fame as a fencing master in his youth. He operated a fencing school in Trevino and apparently traveled around Italy observing the teachings of other schools and masters.

Ultimately di Grassi seems to have developed his own method, which he laid out in great detail in his 1570 work Ragione di adoprar sicuramente l'Arme ("Discourse on Wielding Arms with Safety"). In 1594, a new edition of his book was printed in London under the title His True Arte of Defence, translated by an admirer named Thomas Churchyard and published by an I. Iaggard.

Contents

- 1 Treatise

- 1.1 Preface

- 1.2 Introduction

- 1.3 Single Rapier

- 1.4 Rapier and Dagger

- 1.5 Rapier and Cloak

- 1.6 Rapier and Buckler

- 1.7 Rapier and Square Shield

- 1.8 Rapier and Round Shield

- 1.9 Double Rapiers

- 1.10 Two-Handed Sword

- 1.11 Pole Weapons

- 1.12 Deceits and Falsings (all weapons again)

- 1.13 Physical Training

- 1.14 Copyright and License Summary

- 2 Additional Resources

- 3 References

Treatise

This presentation includes a modernized version of the 1594 English translation, which did not follow the original Italian text with exactness. We intend to replace or expand this with a translation of the Italian, when such becomes available.

Images |

Italian Transcription (1570) |

English Transcription (1594) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Giacomo DiGrassi His True Art of Defense, plainly teaching by infallible Demonstrations, apt Figures and perfect Rules the manner and form how a man without other Teacher or Master may handle all sorts of Weapons as well offensive as defensive: With a Treatise Of Deceit or Falsing: And with a way or Means by private Industry to obtain Strength, Judgement, and Activity |

[Ttl] RAGIONE DI ADOPRAR SICVRAMENTE L'ARME SI DA OFFESA, COME DA DIFESA, Con un Trattato dell'inganno, & con un modo di essitarsi da se stesso, per acquistare forza, giudicio, & prestezza, |

[Ttl] Giacomo Di Grassi his true Arte of Defence, plainlie teaching by infallable Demonstrations, apt Figures and perfect Rules the manner and forme how a man without other Teacher or Master may safelie handle all sortes of Weapons as well offensiue as defensiue: VVith a Treatise Of Disceit or Falsinge: And with a waie or meane by priuate Industrie to obtaine Strength, Iudgement and Actiuitie. | |

First written in Italian by the Fore-said Author, And Englished by I. G. gentleman. |

DI GIACOMO DI GRASSI. CON PRIVILEGIO. |

First written in Italian by the foresaid Author, And Englished by I. G. gentleman. | |

Printed at London for I. I. and are to be sold within Temple Barre at the Signe of the Hand and Starre 1594 |

In Uenetia, appresso Giordano Ziletti, & compagni.

|

Printed at London for I. I and are to be sold within Temple Barre at the Signe of the Hand and Starre 1594. | |

|

[i] To the Right Honorable my L. Borrow Lord Gouernor of the Breil, and Knight of the most honorable order of the Garter, T. C. wisheth continuall Honor, worthines of mind, and learned knowledg, with increas of worldlie Fame, & heauenlie felicitie. HAuing a restlesse desier in the dailie exercises of Pen to present some acceptable peece of work to your L. and finding no one thing so fit for my purpose and your honorable disposition, as the knowledge of Armes and Weapons, which defends life, countrie, & honour, I presumed to preferre a booke to the print (translated out of the Italyan language) of a gentle mans doing that is not so gredie of glory as many glorious writers that eagerly would snatch Fame out of other mens mouthes, by a little labour of their own, But rather keeps his name vnknowen to the world (vnder a shamefast clowd of silence) knowing that vertue shynes best & getteth greatest prayes where it maketh smallest bragg: for the goodnes of the mind seekes no glorious gwerdon, but hopes to reap the reward of well doing among the rypest of iudgement & worthiest of sound consideration, like vnto a man that giueth his goods vnto the poore, and maketh his treasurehouse in heauen, And further to be noted, who can tarrie til the seed sowen in the earth be almost rotten or dead, shal be sure in a boūtiful haruest to reap a goodly crop of corne And better it is to abyde a happie season to see how things will proue, than soddainly to seeke profite where slowlye comes commoditie or any benefit wil rise. Some say, that good writers doe purchase small praise till they be dead, (Hard is that opinion.) and then their Fame shal flowrish & bring foorth the fruite that long lay hid in the earth. [ii] This gentleman, perchaunce, in the like regard smothers vp his credit, and stands carelesse of the worlds report: but I cannot see him so forgotten for his paines in this worke is not little, & his merite must be much that hath in our English tongue published so necessarie a volume in such apt termes & in so bigg a booke (besides the liuely descriptions & models of the same) that shews great knowledge & cunning, great art in the weapon, & great suretie of the man that wisely can vse it, & stoutly execute it. All manner of men allowes knowledge: then where knowledge & courage meetes in one person, there is ods in that match, whatsoeuer manhod & ignorance can say in their own behalfe. The sine book of ryding hath made many good hors-men: and this booke of Fencing will saue many mens lyues, or put comon quarrels out of vre, because the danger is death if ignorant people procure a combate. Here is nothing set downe or speach vsed, but for the preseruation of lyfe and honour of man: most orderly rules, & noble obseruations, enterlaced with wise councell & excellent good wordes, penned from a fowntaine of knowledge and flowing witt, where the reasons runnes as freely as cleere water cōmeth from a Spring or Conduite. Your L. can iudge both of the weapon & words, wherefore there needes no more commendation of the booke: Let it shewe it self, crauing some supportation of your honourable sensure: and finding fauour and passage among the wise, there is no doubt but all good men will like it, and the bad sort will blush to argue against it, as knoweth our liuing Lord, who augment your L. in honour & desyred credit. Your L. in all humbly at commaundement. Thomas Churchyard. | |||

The Author's Epistle unto divers Noble men and Gentlemen |

[i] ALLI MOLTO MAG. SIGNORI Il Sig. Camillo, il Sig. Fabritio, il Sig. Girolamo, già del S. Luigi, il S. Liberale, l'uno & l'altro, S. Luigi Renaldi. Il S. Alberto Onigo, il S. Antonio Bressa, il S. Branca Scolari, il Sig. Lione Bosso, il Sig. Giacomo Sugana, il Sig. Bonsembiante, Onigo, già del Sig. Cavallier, il Sig. Ascanio Federici, il Sig. Agostino Bressa, miei Signori Osseruandissimi. |

[iii] The Authors Epistle vnto diuers Noble men and Gentle-men. | |

Among all the Prayers, wherein through the whole course of my life, I have asked any great thing at Gods hands, I have always most earnestly beseeched, that (although at this present I am verse poore and of base Fortune) he would notwithstanding give me grace to be thankefull, and mindfull of the good turnes which I have received. For among all the disgraces which a man may incurre in this world, there is none in mine opinion which causeth him to become more odious, or a more enimic to mortall men (yea, unto God himselfe) than ingratitude. Wherefore being in Treuiso, by your honours courteously intreated, and of all honourably used, although I practised litle or nought at all to teach you how to handle weapons, for the which purpose I was hyred with an honourable stipend, yet to shewe my selfe in some sort thankefull, I have determined to bestowe the way how toall sortes of weapons with the advantage and safetie. The which my worke, because it shall finde your noble hearts full of valure, will bring foorth such fruite, being but once attentively read over, as that in your said honors will be seene in actes and deedes, which in other men scarsely is comprehended by imagination. And I, who have beene and am most fervently affected to serve your Ls. for asmuch as it is not graunted unto me, (in respect of your divers affaires) to applie the same, and take some paines in teaching as I alwaies desired, have yet by this other waie, left all that imprinted in your noble mindes, which in this honourable exercise may bring a valiant man unto perfection. |

FRA TVTTI i preghi che io per tut to il corso della mia uita ho chiesti a Dio maggiori, di quest'uno l'ho sempre caldamente supplicato. Che quan tunque io mi troui per hora in assai debbole & bassa fortuna, egli nondimeno mi conceda gratia di potermi mostrare grato & cortese de' fauori & beneficii riceuuti. Parendomi che fra tutte le brutture, nelle quali puote l'huomo incorrere in questo mondo, niuna ue ne sia, che piu odioso lo faccia, & inimico a' mortali, & a Dio istesso, che la ingratitudine. Onde essendo io stato dalle Signorie Vostre raccolto in Treuiso, & cortese & honora-tamente trattato da tutti, come che io poco o nulla mi a-doprassi in insegnarle la ragion dell'armi, a che ero da quel-le con honorato stipendio condotto, per dimostrar in parte la gratitudine dell'animo mio, ho deliberato donarle que- [ii] sta mia opera, nella qual mi sforzo di insegnare il modo di adoprar tutte le forte d'armi con auantaggio & sicuramente: la qual, perche trouerà i cuori uostri pieni di ualore, produrrà tal frutto, essendo una uolta letta con attentione, che nelle Signorie Vostre si uedrà quello in fatto, che in altrui à gran pena con l'imaginatione si comprende. Et io che sono stato & son ardentissimo di seruirle, non mi essendo stato concesso per molti suoi affari, di affaticarmi in esercitarle come era il desiderio mio, haurò con quest’altra uia lasciato ne i nobilissimi animi uostri impresso tutto quello che può in quest'honorato essercitio ridurre un'huomo ualoroso a perfettione. |

AMong all the Prayers, wherein through the whole course of my life, I haue asked any great thing at Gods hands, I haue alwayes most earnestly beseeched, that (although at this present I am verie poore and of base Fortune) he would notwithstanding giue me grace to be thankefull and mindfull of the good turnes which I haue receiued. For among all the disgraces which a man may incurre in this world, there is none in mine opinion which causeth him to become more odious, or a more enimie to mortall men (yea, vnto God himselfe) than ingratitude. VVherefore being in Treuiso, by your honours courteously intreated, and of all honourably vsed, although I practised litle or nought at all to teach you how to handle weapons, for the which purpose I was hyred with an honourable stipend, yet to shewe my selfe in some sort thankefull, I haue determined to bestowe this my worke vpon your honours, imploying my whole indeuour to shewe the way how to handle all sortes of weapons with aduantage and safetie. The which my worke, because it shall finde your noble hearts full of valure, will bring foorth such fruite, being but once attentiuely read ouer, as that in your said honors will be seene in actes and deedes, which in other men scarsely is comprehended by imagination. And I, who haue beene and am most feruently affected to serue your Ls. forasmuch as it is not graunted vnto me, (in respect of your diuers affaires) to applie the same, and take some paines inteaching as I alwaies desired, haue yet by this other waie, left all that imprinted in your noble mindes, which in this honourable exercise may bring a valiant man vnto perfection.

| |

Therefore I humbly beseech your honours, that with the same liberall mindes, with the which you accepted of mee, your Ls will also receive these my indevours, & vouchsafe so to protect them, as I have alwaies, and wil defend your honours most pure and undefiled. Wherein, if I perceive this my first childbirth (as I have only published it to thentent to help & teach others) to be to the generall satisfaction of all I will so straine my endevours in an other worke which shortly shall shew the way both how to handle all those weapons on horse-backe which here are taught on foote, as also all other weapons whatsoever. Your honours most affectionate servant, Giacomo di Grassi of Medena |

Supplico dunque le Signorie uostre, che con quell'animo liberale, che accettorono me, riceuano questa mia fatica, havendola in quella protettione che io ho sempre hauuto & haurò il chiarissimo honor delle Signorie uostre: che se io conoscerò questo mio primiero parto, si come io l'ho solamente per giouare & insegnare publicato, sia di uniuersale sodisfattione, mi sforzerò in un'altro, & fra poco tempo, insegnare il modo di adoprar a cauallo tutte quelle sorti d'armi, che qui s'insegnano a piede, & dell'altre ancora. Di Venetia, adi 8. Marzo. 1570. Di VV. SS. Seruitor Affettionatissimo

|

Therefore I humbly beseech your honours, that with the same liberall mindes, with the which you accepted of mee, your Ls: will also receiue these my indeuours, & vouchsafe so to protect them, as I haue alwaies, and wil defend your honours most pure and vndesiled. VVherein, if I perceiue this my first childbirth (as I haue only published it to thentent to help & teach others) to be to the generall satisfaction of all I will so straine my endeuours in an other worke which shortly shall shew the way both how to handle all those weapons on horse-backe which here are taught on foote, as also all other weapons whatsoeuer. Your honours most affectionate seruant.

| |

[iii] A I LETTORI. SI COME dalle fascie portiamo con noi un quasi sfrenato desiderio di sapere, cosi da l'esser po fatti ragioneuoli nasce in noi una lodeuole & ardente uoglia d'insegnare, il che quando non fosse non si uedrebbe perauentura il mondo di tante arti e scienze ripieno. |

[iv] The Author, to the Reader. EVen as from our swathing bands wee carrie with vs (as it were) an vnbridled desire of knowledge: So afterwardes, hauing attained to the perfection therof, there groweth in vs a certaine laudable and feruent affection to teach others: The which, if it were not so, the world happily should not be seene so replenished with Artes and Sciences. | ||

|

Percio che non essendo tutti gli huomini atti alla contemplatione & inuestigatione delle cose, nè meno a ciascuno concessa da Dio la gratia di poter con la mente leuarsi da terra, & inuestigando trouar le cause delle cose, & quelle compartir a quelli che meno uolentieri s'affaticana; accaderebbe che una parte de gli huomini a guisa di Signori & padroni dominarebbono, & gli altri come serui uilissimi in perpetue tenebre auolti tolererebbono una uita indegna dell'humana conditione. La onde al parer mio è cosa ragioneuole far, altrui partecipe di quello che si ha con molto studio & fatica inuestigando ritrouato. Sendo dunque io sin da fanciullo sommamente dilettato del maneggio dell'armi, dopo l'hauer molto tempo esercitato il corpo in esse, ho uoluto uedere i piu eccellenti maestri di quest'arte, i quali ho auertito hauere tutti, modi diuersi di insegnare l'uno da l'altro molto differenti, quasi che questo mestiero fosse senza ordine & regola, & dipendesse tutto dal ceruello, & ghiribizzo di chi ne fa professione, nè fosse possibile in quello esercitio tanto honorato ritrouarsi, come in tutte l'altre arti e scienze, una sola uia buona e uera, col mezo della quale si potesse hauere intera cognitione di quanto si puo far con l'armi, senza lam bicarsi tutto dì il ceruello ad imparar hoggi un colpo da un maestro, diman da un'altro, affaticandosi d'intorno a i particolari, la cognitione de' quali è infinita, & per ciò impossibile. Però da honesto desio di giouare sospinto, tutto a questa contemplatione mi diedi, con speranza quando che fosse di poter ritrouare i principii & le uere cagioni di questa arte, & in poca somma & certo ordine ridurre il confuso & infinito numero de' colpi: i quali principii essendo pochi, & per ciò facili ad esser da qualunque persona intesi & collocati nella memoria; senza alcun dubio in poco tempo & con poca fatica apriranno una larghissima strada a saper tutto quello che in essa arte si contiene. Nè sono di ciò, si come io stimo, punto rimaso ingannato: percioche al fine dopo molto pensare [iv] ho ritrouato questa uera arte, dalla qual sola dipende la cognitione di quanto si puo far con l'armi in mano; non tanto di quelle che hoggidì si trouano, ma di quelle ancora che si troueranno nel tempo auenire, essendo ella fondata su la offesa & difesa, ambedue le quali si fanno nella linea retta e circulare, che in altro modo non si puo offendere nè difendere. |

For if men generally were not apt to contemplation and searching out of things: Or if God had not bestowed vpon euery man the grace, to be able to lift vp his minde from the earth, and by searching to finde out the causes thereof, and to imparte them to those who are lesse willing to take any paines therein: it would come to passe, that the one parte of men, as Lordes and Masters, should beare rule, and the other parte as vyle slaues, wrapped in perpetuall darknesse, should suffer and lead a life vnworthie the condition of man. Wherefore, in mine opinion it standes with great reason that a man participate that vnto others which he hath searched and found out by his great studie & trauaile. And therefore, I being euen from my childhood greatly delighted in the handling of weapons: after I had spent much time in the exercise thereof, was desyrous to see and beholde the most excellent and expert masters of this Arte, whome I haue generally marked, to teach after diuers wayes, much differing one from another, as though this misterie were destitute of order & rule, or depended onely vpon imagination, or on the deuise of him who professeth the same: Or as though it were a matter impossible to find out in this honourable exercise (as well as in all other Artes and Sciences) one onely good and true way, whereby a man may attaine to the intire knowledge of as much as may be practised with the weapon, not depending altogether vpon his owne head, or learning one blowe to day of one master, on the morowe of another, thereby busying himselfe about perticulars, the knowledge whereof is infinite, therefore impossible. Whereupon being forced, through a certaine honest desire which I beare to helpe others, I gaue my selfe wholy to the con- [v] templation thereof: hoping that at the length, I shoulde finde out the true principles and groundes of this Arte, and reduce the confused and infinite number of blowes into a compendious summe and certaine order: The which principles being but fewe, and therefore easie to be knowen and borne away, without doubt in small time, and little trauaile, will open a most large entrance to the vnderstanding of all that which is contained in this Arte. Neither was I in this frustrate at all of my expectation: For in conclusion after much deliberation, I haue found out this Arte, from the which onely dependeth the knowledge of all that which a man may performe with a weapon in his hand, and not onely with those weapons which are found out in these our dayes, but also with those that shall be inuented in time to come: Considering this Arte is grounded vpon Offence and Defence, both the which are practised in the straight and circuler lynes, for that a man may not otherwise either strike or defend. | ||

Et uolendo insegnar questa ragione dell'adoprar l'armi con quel maggior ordine & con quella maggior chiarezza che sia possibile, ho posto nel primo loco i principii di tutta l'arte nominando gli Auertimenti, i qua li essendo per sua natura notissimi a ciascuna persona di sana mente, non ho fatto altro che solamente raccontarli senza renderne ragion alcuna, come cosa superflua. |

And because I purpose to teach how to handle the Weapon, as orderly and plainly as is possible: I haue first of all layd down the principles or groundes of all the Arte, calling them Aduertisements, the which, being of their owne nature verie well knowen to all those that are in their perfect wittes: I haue done no other then barely declared them, vvithout rendring any further reason, as being a thing superfluous. | ||

Dopo questi principii ho trattato delle cose piu semplici, & de li poi alle composite ascendendo, dimostro quello che in tutto l'armi si possa fare. Et perche nell'insegnar le scienze & l'arti, si denono molto piu estimar le cose, che le parole, però non ho uoluto elegger un modo di parlare copioso, & sonoro, ma uno breue & familiare: il qual modo di parlare si come in poco fascio contiene in se & molte cose & grandi, cosi ricerca un lettore acuto & tardo, il quale uoglia a passo a passo penetrar nella midolla delle cose. |

These principles being declared, I haue next handled those things, vvhich are, and be, of themselues, Simple, then (ascending vp to those that are Compound) I shewe that vvhich may be generally done in the handling of all Weapons. And because, in teaching of Artes and Sciences, Things are more to be esteemed of than VVordes, therefore I vvould not choose in the handling hereof a copious and sounding kinde of speach, but rather that vvhich is more briefe and familiar. Which maner of speach as in a small bundle, it containeth diuers weightie things, so it craueth a slowe and discreete Reader, who will soft and faire pearce into the verie Marrowe thereof. | ||

Prego dunque il benigno lettore che tale si dimostri nel leggere la presente mia opera, sendo sicuro in tal modo leggendola di deuerne raccogliere grandissimo frutto & honore: nè è dubio alcuno che colui, il quale sarà fornito a bastanza di questa cognitione, & haurà a proportione la persona esercitata, non sia di gran lunga superiore ad ogni altro, quando però ui sarà da luna & l'altra parte egual forza & uelocità. |

For this cause I beseech the gentle Reader to shewe himselfe such a one in the reading of this my present worke, assuring him selfe by so reading it, to reape great profite and honour thereby. And [vi] Not doubting but that he (who is sufficientlie furnished with this knowledge, and hath his bodie proporcionably exercised thereunto) shall far surmount anie other although he be indewed with equal force and swiftnes. | ||

Et percioche questa arte è un principal membro della scienza militare, la quale insieme con le lettere è l’ornamento del mondo, però non si deue ella esercitare nelle brighe & risse, che si fanno per le contrade, ma come honoratissimi cauallieri riserbarsi di adoprarla per l'honor della patria, del suo Principe, per l'honor delle Donne, & di loro stessi, & finalmente per la uittoria de gli esserciti. |

Moreouer, because this art is a principal member of the Militarte profession, vvhich alltogether (vvith learning) is the ornament of all the World, Therefore it ought not to be exercised in Braules and Fraies, as men commonlie practise in euerie shire, but as honorable Knights, ought to reserue themselues, & exercise it for the aduantage of their Cuntry, the honour of vveomen, and conqueringe of Hostes and armies. | ||

|

[vii] An Aduertisement to the curteous reader. GOod Reader, before thou enter into the discourse of the hidden knowledge of this honourable excerise of the weapon now layd open and manifested by the Author of this worke, & in such perfectnes translated out of the Italian tongue, as all or most of the marshal mynded gentlemen of England cannot but commend, and no one person of indifferent iudgement can iustly be offended with, seeing that whatsoeuer herein is discoursed, tendeth to no other vse, but the defence of mans life and reputation: I thought good to aduertise thee that in some places of this booke by reason of the aequiuocation of certaine Italian wordes, the weapons may doubtfully be construed in English. Therefore sometimes fynding this worde Sworde generally vsed, I take it to haue beene the better translated, if in steede thereof the Rapier had beene inserted: a weapon more vsuall for Gentlemens wearing, and fittest for causes of offence and defence: Besides that, in Italie where Rapier and Dagger is commonly worne and vsed, the Sworde (if it be not an arming Sworde) is not spoken of. Yet would I not the sence so strictly to be construed, that the vse of so honourable a weapon be vtterly [viii] reiected, but so redd, as by the right and perfect vnderstanding of the one, thy iudgement may som what be augmented in managing of the other: Knowing right well, that as the practise and vse of the first is commendable amongst them, so the second cannot so farre be condemned, but that the wearing thereof may well commend a man of valour and reputation amongst vs. The Sworde and Buckler fight was long while allowed in England (and yet practise in all sortes of weapons is praisworthie,) but now being layd downe, the sworde but with Seruing-men is not much regarded, and the Rapier fight generally allowed, as a wapon because most perilous, therefore most feared, and thereupon priuate quarrels and common frayes soonest shunned. | |||

|

But this peece of work, gentle Reader, is so gallantly set out in euery point and parcell, the obscurest secrets of the handling of the weapon so clerely vnfolded, and the perfect demeaning of the bodie vpon all and sudden occasions so learnedly discoursed, as will glad the vnder stander thereof, & sound to the glory of all good Masters of Defence, because their Arte is herein so honoured, and their knowledge (which some men count infinite) in so singuler a science, drawen into such Grounds and Principles, as no wise man of an vnpartiall iudgement, [ix] and of what profession soeuer, but will confesse himself in curtesie farre indebted both to the Author & Translator of this so necessarie a Treatise, whereby he may learne not onely through reading & remembring to furnish his minde with resolute instructions, but also by practise and exercise gallantly to perfourme any conceited enterprise with a discreete and orderly carriage of his bodie, vpon all occasions whatsoeuer. | |||

Gentle Reader, what other escapes or mistakings shall come to thy viewe, either friendly intreate thee to beare with them, or curteously with thy penne for thine owne vse to amend them. Fare-well. | |||

[x] The Sortes of VVeapons handled in this Treatise. THe single Rapier, Or single Sworde. Falsing of Blowes and Thrusts. At single rapier &c. class="noline" | |

Images |

Italian Transcription (1570) |

English Transcription (1594) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The true Art of Defense exactly teaching the manner how to handle weapons safely, as well offensive as defensive, with a Treatise of deceit or Falsing, And with a mean or way how a man may practice of himself to get Strength, Judgment, and Activity. |

[1] DELLA VERA ARTE DI adoprare le arme. Cap. I. |

[1] The true Art of Defence exactlie teachinge the manner how to handle weapons safelie, aswel offensiue as defensiue, With a Treatise of Disceit or Falsing, And with a mean or waie how a man may practise of himselfe to gett Strength, Iudgement, and Actiuitie. | ||||

There is no doubt but that the Honorable exercise of the Weapon is made right perfect by means of two things, to wit: Judgment and Force: Because by the one, we know the manner and time to handle the weapon (how, or whatsoever occasion serves:) And by the other we have the power to execute therewith, in due time with advantage. |

NON é dubio alcuno l'essercitio honoratissimo de l'arme farsi per due cose perfettissimo, cioe per il giuditio,& per la forza , percioche da l'uno s'acquista la cognitione, del modo & del tempo di operare in qual si uoglia accorrenza,& da l'altro si sa habili a poter il tutto esequire in tépo debito & con auantagio, |

THere is no doubt but that the Honorable exercise of the Weapon is made right perfect by meanes of two thinges, to witt: Iudgment and Force: Because by the one, we know the manner and time to handle the wepon (how, or whatsoeuer occasion serueth:) And by the other we haue power to execute therewith, in due time with aduauntage. | ||||

And because, the knowledge of the manner and Time to strike and defend, does of itself teach us the skill how to reason and dispute thereof only, and the end and scope of this Art consists not in reasoning, but in doing: Therefore to him that is desirous to prove so cunning in this Art, as is needful, It is requisite not only that he be able to judge, but also that he be strong and active to put in execution all that which his judgment comprehends and sees. And this may not be done without strength and activity of body: The which if happily it be feeble, slow, or not of power to sustain the weight of blows, Or if it take not advantage to strike when time requires, it utterly remains overtaken with disgrace and danger: the which faults (as appears) proceed not from the Art, but from the Instrument badly handled in the action. |

per theil cono scer il modo & iépa di ferire e riparar per se solo gioua solamente al saperne ragionare, il fine di quest'arte non e il dire ma il fa re.onde a uoler in essa riuscire quanto si conuiene egli e dibisogno oltra l'hauer guiditio, hauer anco modo di poter prestissimo esequire quel tanto che il giuditio comprehende & uede, & questo non si puo fare se non con la forza & destrezza del corpo, la quale se perauentura é debole o tarda ouero che non può sostentare i pesi delle botte, ouero per non andar a ferir quando il tempo richiede resta auilluppato. i quali errori come si uede , non procedono da l'arte ma da l'instruméto mal accomodato ad exequirla; |

And because, the knowledge of the manner and Time to strike and defende, dooth of it selfe teach vs the skil how to reason and dispute thereof onely, and the end and scope of this Art consisteth not in reasoning, but in dooinge: Therefore to him that is desierous to proue so cunning in this Art, as is needfull, It is requisite not onelie that he be able to iudge, but also that he be stronge and actiue to put in execution all that which his iudgement comprehendeth and seeth. And this may not bee done without strength and actiuitie of bodie: The which if happelie it bee [2] feeble, slowe, or not of power to sustaine the weight of blowes, Or if it take not aduauntage to strike when time requiereth, it vtterlie remaineth ouertaken with disgrace and daunger: the which falts (as appeareth) proceed not from the Art, but from the Instrument badly handled in the action. | ||||

Therefore let every man that is desirous to practice this Art, endeavor himself to get strength and agility of body, assuring himself, that judgment without this activity and force, avails little or nothing: Yea happily gives occasion of hurt and spoil. For men being blinded in their own judgments, and presuming thereon, because they know how, and what they ought to do, give many times the onset and enterprise, but yet, never perform it in act. |

peró s'af faticherà ogn'uno che uorrà in quest' adoperarsi di acquistar questa forza,tenendo per certo che il giuditio fenza questa forza & destrezza sia o di poca o di niuna utilita,ma forse di danno, percioche gli huomini acietati dal giuditio, per sapere come le co se si debbano fare, si pongono a imprese nelle quali poscia non riescono in fatti; |

Therefore let euerie man that is desierous to practise this Art, indeuor himselfe to get strength and agilitie of bodie, assuringe himself, that iudgment without this actiuitie and force, auaileth litle or nothinge: Yea, happelie giueth occasion of hurt and spoile. For men beinge blinded in their owne iudgements, and presuminge thereon, because they know how, and what they ought to doo, giue manie times the onset and enterprise, but yet, neuer perfourme it in act. | ||||

But least I seem to ground this Art upon dreams and monstrous imaginations (having before laid down, that strength of body is very necessary to attain to the perfection of this Art, it being one of the two principal beginnings first laid down, and not as yet declared the way how to come by and procure the same) I have determined in the entrance of this work, to prescribe the manner how to obtain judgment, and in the end thereof by way of Treatise to show the means (as far as appertains to this Art) by the which a man by his own endeavor and travail, may get strength and activity of body, to such purpose and effect, that by the instructions and reasons, which shall be given him, he may easily without other master or teacher, become both strong, active and skillful. |

ma percioche il dir che la forza a quest'arte sia necessaria & non dar il modo d'acquistarla , essendo ella uno de dua capi principali farebbe un fondar l'arte infogni & inchimere, percio ho deliberato in principio di quest'epra dare il modo di acquistar il giuditio, & in fine di essa far un trattato come [2] l'huomò si possa da se stesso esercitare per acquistar, forza & prestezza, modo per quanto a quest'arte appertiene, di modo che potra ciascuno con le ragioni che si daranno diuenir senz'altro maestro & presto & forte. |

But least I seeme to ground this Art vppon dreames and monstrous imaginations (hauinge before laid downe, that strength of bodie is very necessarie to attaine to the perfection of this Art, it beinge one of the two principall beeginninges first layd downe, and not as yet declared the way how to come by and procure the same) I haue determined in the entrance of this worke, to prescribe first the manner how to obtaine iudgemēt, and in the end thereof by way of Treatise to shew the meanes (as farre forth as appertaineth to this Art) by the which a man by his owne indeuoure and trauaile, may get strength and actiuitie of bodie, to such purpose and effect, that by the iustruc- [3] tions and reasons, which shal be here giuen him, he may easely without other master or teacher, become both stronge, actiue and skilful. | ||||

The means how to obtain judgment Although I have very much in a manner in all quarters of Italy, seen most excellent professors of this Art, to teach in their Schools, and practice privately in the Lists to train up their Scholars. Yet I do not remember that I ever saw any man so thoroughly endowed with this first part, to wit, Judgment, that behalf required. |

DEL MODO DI AQVISTAR il gluditio. PER molto che io quali in tutte le parti d'Italia habbia ueduto professori eccelentisimi di quest'arte, & insegnar nelle lor schuo le & exercitar secretamente per condur in stecato: non so di hauer ne ueduto alcuno, ìlgual habbia posseduta questa parte del giuditio come si conuiene puo eßer che l habbino |

The meanes how to obtain Iudgement. ALthough I haue verye much in a manner in all quarters of Italie, seene most excellent professors of this Art, to teach in their Schols, and practise priuately in the Listes to traine vp their Schollers. Yet I doo not remember that euer I saw anie man so throughly indewed with this first part, to wit, Iudgement, as is in that behalfe required. | ||||

And it may be that they keep it secret of purpose: for amongst diverse disorderly blows, you might have seen some of them most gallantly bestowed, not without evident conjecture of deep judgment. But howsoever it be seeing I purpose to further this Art, in what I may, I will speak of this first part as aptly to the purpose, as I can. |

& che la tenghino pùre tra molei colpi sregolati, se ne ueggono di bellissimi et giuditiosissimimi, ma sia comúq sì uoglia, io hauendo intentione di giouar in quest'arte quanto posso, uoglio in questa parte dir tutto quello che mi pare a proposito. |

And it may bee that they keep it in secreat of purpose: for amongst diuers disorderlie blowes, you might haue seen some of them most gallantlie bestowed, not without euident coniecture of deepe iudgment. But howsoeuer it bee seeinge I purpose to further this Art, in what I may, I wil speak of this first part as aptly to the purpose, as I can. | ||||

It is therefore to be considered that man by so much the more waxes fearful or bold, by how much the more he knows how to avoid or not to eschew danger. |

Deuesi dunque sapere che l'huomo in tanto diuiene timido & ardito in quanto conosce di poter uietar non uietar il pericolo, |

It is therefore to be considered, that man by so much the more waxeth fearefull or boulde, by how much the more he knoweth how t'auoid [4] or not to eschew daunger. | ||||

But to attain to this knowledge, it is most necessary that he always keep steadfastly in memory all these advertisements underwritten, from which springs all the knowledge of this Art. Neither is it possible without them to perform any perfect action for the which a man may give a reason. But if it so fall out that any man (not having the knowledge of these advertisements) perform any sure act, which may be said to be handled with judgment, that proceeds of no other thing, than of very nature, and of the mind, which of itself naturally conceives all these advertisements. |

ma per hauer questa cognitione, eglie di bisogno hauer continuamente nella memoria fili tutti gli infrascri ti auertimenti, dai quali nafte tutta la cognitione di quest'arte, ne e possibile senza questi far cosa con ragione ne che sia bona et so pu re auiene che alcuno senza hauer saputo questi, habbia fatto cosa con giuditio & utile, questo non uiene da altro, che dalla natura anima, la quale per se conosce tutti questi auertimenti, |

The meanes how to obtain Iudgement. ALthough I haue verye much in a manner in all quarters of Italie, seene most excellent professors of this Art, to teach in their Schols, and practise priuately in the Listes to traine vp their Schollers. Yet I doo not remember that euer I saw anie man so throughly indewed with this first part, to wit, Iudgement, as is in that behalfe required. | ||||

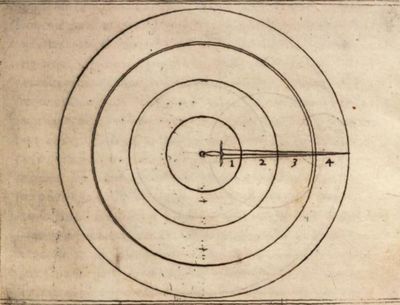

First, that the right or straight Line is of all other the shortest: wherefore if a man would strike in the shortest line, it is requisite that he strike in the straight line. |

i quali son questi, che la linea retta e la piu breue d ognaltra & pero qua do si uorra ferir per la piu corta sara di bisogno ferir per la li, nea retta. |

1 First, that the right or streight Line is of all other the shortest: wherefore if a man would strike in the shortest lyne, it is requisite that he strike in the streightline. | ||||

Secondly, he that is nearest, hits soonest. Out of which advertisement a man may reap this profit, that seeing the enemies sword far off, aloft and ready to strike, he may first strike the enemy, before he himself be struck. |

il secondo é, chi e piu uicino giunge piu presto, dal qual auertimento nasce questa, utilità che uedendosi la spa= [3] da da de l'inimico lontana o alta per ferire all'hura si ferisce prima che esser ferito, |

2 Secondly, he that is neerest, hitteth soonest. Out of which aduertisment a man may reap this profit, that seeing the enemies sword farr off, aloft and readie to strik, he may first strik the enemie, before he himselfe be striken. | ||||

Thirdly, a Circle that goes compassing bears more force in the extremity of the circumference, than in the center thereof. |

il terzo é che un cerchio che giri ha maggior forza nella circonferenza, che uerso il centro, |

3 Thirdly, a Circle that goeth compassinge beareth more force in the extremitie of the circumference, then in the center thereof. | ||||

Fourthly, a man may more easily withstand a small than a great force. |

Il quarto che piu facilmente si resiste alla poca che alla molta forza, |

4 Fourthly, a man may more easely withstand a small then a great force. | ||||

Fifthly, every motion is accomplished in time. |

Il quinto che ogni moto è fatto in tempo. |

5 Fifthly, euerie motion is accomplished in tyme. | ||||

That by these Rules a man may get judgment, is most clear, seeing there is no other thing required in this Art, than to strike with advantage, and defend with safety. |

Che da questi auertimenti ne nafta il giuditio e cola chiarißima, percio che altro, non si ricercha in quest'arte che ferir con auantaggio & difendersi sicuramente, |

That by these Rules a man may get iudgment, [5] it is most cleere, seing there is no other thinge required in this Art, then to strike with aduantage, and defend with safetie. | ||||

This is done, when one strikes in the right line, by giving a thrust, or by delivering an edgeblow with that place of the sword, where it carries the most force, first striking the enemy before he be struck: The which is performed, when he perceives himself to be more near his enemy, in which case, he must nimbly deliver it. For there are a few nay there is no man at all, who (perceiving himself ready to be struck) gives not back, and forsakes to perform every other motion which he has begun. |

il che sì fa ferendo per linea retta di punta, o di taglio dotte la spada ha piu tori ferendo prima l'inimico che esser ferito, il che si fa quan do si conosce di esser piu uicino all'inimico, ne quali casi si spinge, per che pochi o niuno è che sentendo si ferir non dia in dietro regi di fare ogn'altro moto c'hauesse incominciato, |

This is done, when one striketh in the right line, by giuing a thurst, or by delyuering an edgeblow with that place of the sword, where it carrieth most force, first striking the enemie beefore he be stroken: The which is perfounned, when he perceiueth him selfe to be more nere his enemie, in which case, he must nimbly deliuer it. For there are few nay there is no man at all, who (perceiuing himselfe readie to be stroken) giues not back, and forsaketh to performe euerie other motion which he hath begun. | ||||

And forasmuch, as he knows that every motion is made in time, he endeavors himself so to strike and defend, that he may use as few motions as is possible, and therein to spend as little time. And as his enemy moves much in diverse times he may be advertised hereby, to strike him in one or more of those times, so out of all due time spent. |

& sapendo poi che ogni moto si fa in tempo, si procura per ferir & riparar di far manco moti che sia possibile per consumar poco tempo, & tacendone molti l'inimico, si puo star auertito di ferirlo, fotto uno o piu tempi indebitamente consumati, |

And forasmuch, as he knoweth that euery motion is made in time, he indeuoreth himselfe so to strik and defend, that he may vse as few motions as is possible, and therein to spend as litle time, And as his enemie moueth much in diuers times he may be aduertised hereby, to strike him in one or more of those times, so out of al due time spent. | ||||

The division of the art Before I come to a more particular declaration of this Art, it is requisite I use some general division. Wherefore it is to be understood, that as in all other arts, so likewise in this (men forsaking the true science thereof, in hope peradventure to overcome rather by deceit than true manhood) have found a new manner of skirmishing full of falses and slips. The which because it somewhat and sometimes prevails against those who are either fearful or ignorant of their grounds and principals, I am constrained to divide this Art into two Arts or Sciences, calling the one the True, the other, the False art: But withal giving every man to understand, that falsehood has no advantage against true Art, but rather is most hurtful and deadly to him that uses. |

DELLA DIVISIONE de l'arte. PRIMA che si uenga a piu particolare dichiaratione di questa arte, fà dibisogno diuiderla; onde é da' sapere che si come quasi in tutte l'altre arti, in questa ancora, gli huomini, lasciando la uera scienza sperando forse piu con la bugia, che con il nero uittoriosi, hanno trouato un nuouo modo di schermir pieno di finte & di inganni ilquale essendo di qualche utilità contra quelli che o sono timidi, o sono ignoranti de i principÿ, pero fino sforzato a diuidere quest'arte in due, chiamando l'una, uera, & laltra, [4] inganneuole; auertendo però ciascuno, l'inganno contra la uera arte non esser di profitto alcuno anzi, di grandissimo danno & mortale a chi l'usa; |

The diuision of the Art. BEfore I come to a more perticuler de claration of this Art, it is requisite I vse some generall diuision. Wherefore it is to be vnderstood, that as in all other arts, so likewise in this (men forsaking the true science thereof, in hope perad- [6] uenture to ouercome rather by disceit then true manhood) haue found out a new maner of skirmishing ful of falses and slips. The which because it some what and some times preualeth against those who are either fearfull or ignorant of their groundes and principals, I am constrayned to diuide this Art into two Arts or Sciences, callinge thone the True, the other, the False art: But withall giuing euerie man to vnderstand, that falsehood hath no aduauntage against true Art, but rather is most hurtfull and deadlie to him that vseth it. | ||||

Therefore casting away deceit for this present, which shall hereafter be handled in his proper place and restraining myself to the truth, which is the true and principal desire of my heart, presupposing that Justice (which in every occasion approaches nearest unto truth) obtains always the superiority, I say whosoever minds to exercise himself in this true and honorable Art or Science, it is requisite that he be endued with deep Judgment, a valiant heart and great activity, In which three qualities this exercise does as it were delight, live and flourish. |

lasciando dunque da parte per hora l'inganno delquale si tratterà poi a suo loco & restringendomi alla uerità laquale e il uero & principal desiderio del anima nostra, presuponendo che la giustitia uicinissima alla ueritàin ogni occasione sia sempre superiore, dico a chiunque uol in tal mestiero essercitarsi; gli e dibisogno hauer fornivo giuditio, ani moso core, & gran prestezza nelle quali tre cose si mantiene é ui ue tutto questo esercitio. |